Iron ore

The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red.

[2] In 2011 the Financial Times quoted Christopher LaFemina, mining analyst at Barclays Capital, saying that iron ore is "more integral to the global economy than any other commodity, except perhaps oil".

[3] Elemental iron is virtually absent on the Earth's surface except as iron-nickel alloys from meteorites and very rare forms of deep mantle xenoliths.

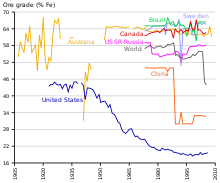

Historically, much of the iron ore utilized by industrialized societies has been mined from predominantly hematite deposits with grades of around 70% Fe.

The waste comes in two forms: non-ore bedrock in the mine (overburden or interburden locally known as mullock), and unwanted minerals, which are an intrinsic part of the ore rock itself (gangue).

As of 2019, magnetite iron ore is mined in Minnesota and Michigan in the United States, eastern Canada, and northern Sweden.

Direct-shipping iron ore (DSO) deposits (typically composed of hematite) are currently exploited on all continents except Antarctica, with the largest intensity in South America, Australia, and Asia.

[10] A few iron ore deposits, notably in Chile, are formed from volcanic flows containing significant accumulations of magnetite phenocrysts.

Another, minor, source of iron ores are magmatic accumulations in layered intrusions which contain a typically titanium-bearing magnetite, often with vanadium.

Magnetite is magnetic, and hence easily separated from the gangue minerals and capable of producing a high-grade concentrate with very low levels of impurities.

Magnetite concentrate grades are generally in excess of 70% iron by weight and usually are low in phosphorus, aluminium, titanium, and silica and demand a premium price.

One method relies on passing the finely-crushed ore over a slurry containing magnetite or other agent such as ferrosilicon which increases its density.

[clarification needed] Iron-rich rocks are common worldwide, but ore-grade commercial mining operations are dominated by the countries listed in the table aside.

[24] It is highly capital intensive, and requires significant investment in infrastructure such as rail in order to transport the ore from the mine to a freight ship.

The world's largest producer of iron ore is the Brazilian mining corporation Vale, followed by Australian companies Rio Tinto Group and BHP.

such as oxidised ferruginous hardcaps, for instance laterite iron ore deposits near Lake Argyle in Western Australia.

[25] Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Jharkhand, Odisha, Goa, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Rajasthan, and Tamil Nadu are the principal Indian producers of iron ore. World consumption of iron ore grows 10% per year [citation needed] on average with the main consumers being China, Japan, Korea, the United States, and the European Union.

Over the last 40 years, iron ore prices have been decided in closed-door negotiations between the small handful of miners and steelmakers which dominate both spot and contract markets.

Until 2006, prices were determined in annual benchmark negotiations between the main iron ore producers (BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto, and Vale S.A.) and Japanese importers.

[3] Singapore Mercantile Exchange (SMX) has launched the world's first global iron ore futures contract, based on the Metal Bulletin Iron Ore Index (MBIOI) which uses daily price data from a broad spectrum of industry participants and independent Chinese steel consultancy and data provider Shanghai Steelhome's widespread contact base of steel producers and iron ore traders across China.

The inclusion of even small amounts of some elements can have profound effects on the behavioral characteristics of a batch of iron or the operation of a smelter.

British metallurgist Thomas Turner reported that silicon also reduces shrinkage and the formation of blowholes, lowering the number of bad castings.

It also increases the depth of hardening due to quenching, but at the same time also decreases the solubility of carbon in iron at high temperatures.

This would decrease its usefulness in making blister steel (cementation), where the speed and amount of carbon absorption is the overriding consideration.

Although bar iron is usually worked hot, its uses[example needed] often require it to be tough, bendable, and resistant to shock at room temperature.

However, removing all the contaminant by fluxing or smelting is complicated, and so desirable iron ores must generally be low in phosphorus to begin with.

However, when brick began to be used for hearths and the interior of blast furnaces, the amount of aluminium contamination increased dramatically.

It is generally avoided, because it is difficult to work, except in China where high-sulfur cast iron, some as high as 0.57%, made with coal and coke, was used to make bells and chimes.

Coal was not used in Europe (unlike China) as a fuel for smelting because it contains sulfur and therefore causes hot short iron.

The combined action of rain, bacteria, and heat oxidize the sulfides to sulfuric acid and sulfates, which are water-soluble and leached out.

25 October 2010 - 4 August 2022