Iron fertilization

A study in 2017 considered that the method is unproven; the sequestering efficiency was low and sometimes no effect was seen and the amount of iron deposits needed to make a small cut in the carbon emissions would be in the million tons per year.

[8] However since 2021, interest is renewed in the potential of iron fertilization, among other from a white paper study of NOAA, the US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, which rated iron fertilization as having "moderate potential for cost, scalability and how long carbon might be stored compared to other marine sequestration ideas" [9] Approximately 25 per cent of the ocean surface has ample macronutrients, with little plant biomass (as defined by chlorophyll).

It has been shown that reduction in the number of sperm whales in the Southern Ocean has resulted in a 200,000 tonnes/yr decrease in the atmospheric carbon uptake, possibly due to limited phytoplankton growth.

When these organisms die they sink to the ocean floor where their carbonate skeletons can form a major component of the carbon-rich deep sea precipitation, thousands of meters below plankton blooms, known as marine snow.

)[28][29] and substantial part of rest of the deposits that sink beneath plankton blooms may be re-dissolved in the water and gets transferred to the surface where it eventually returns to the atmosphere, thus, nullifying any possible intended effects regarding carbon sequestration.

[35] Assuming the ideal conditions, the upper estimates for possible effects of iron fertilisation in slowing down global warming is about 0.3W/m2 of averaged negative forcing which can offset roughly 15–20% of the current anthropogenic CO2 emissions.

[36][37][38] This approach, which stimulates phytoplankton growth by introducing iron into nutrient-poor regions of the ocean, could be seen as a potentially easy and scalable method to reduce atmospheric CO2 levels.

However, while it offers a theoretical means of mitigating climate change, ocean iron fertilisation remains highly controversial and debated due to its potential negative impacts on marine ecosystems.

[42][43][44][45][46][47][48] Excessive iron may also alter the structure of plankton communities, potentially favouring certain species over others, thereby reducing the diversity vital for a healthy marine ecosystem.

[49] Moreover, iron fertilisation can trigger expansive phytoplankton blooms, which, as they decompose, could create hypoxic or anoxic zones in the ocean, posing severe risks to marine life and biodiversity.

[50][51] For example, trials in the Southern Ocean, including the SOFeX experiments, demonstrated that iron fertilisation can lead to the rapid growth of harmful algae, with potential consequences for local ecosystems and food chains.

[56] Iron(III) chloride added to the troposphere could increase natural cooling effects including methane removal, cloud brightening and ocean fertilization, helping to prevent or reverse global warming.

He died shortly thereafter during preparations for Ironex I,[60] a proof of concept research voyage, which was successfully carried out near the Galapagos Islands in 1993 by his colleagues at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories.

[61] Thereafter 12 international ocean studies examined the phenomenon: John Martin, director of the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, hypothesized that the low levels of phytoplankton in these regions are due to a lack of iron.

[100] However, many experts contend that changes in fishery stocks since 2012 cannot necessarily be attributed to the 2012 iron fertilization; many factors contribute to predictive models, and most data from the experiment are considered to be of questionable scientific value.

[102] In 2022, a UK/India research team plans to place iron-coated rice husks in the Arabian Sea, to test whether increasing time at the surface can stimulate a bloom using less iron.

[105] The maximum possible result from iron fertilization, assuming the most favourable conditions and disregarding practical considerations, is 0.29 W/m2 of globally averaged negative forcing,[106] offsetting 1/6 of current levels of anthropogenic CO2 emissions.

Particles this small are easier for cyanobacteria and other phytoplankton to incorporate and the churning of surface waters keeps them in the euphotic or sunlit biologically active depths without sinking for long periods.

[citation needed] When these organisms die their carbonate skeletons sink relatively quickly and form a major component of the carbon-rich deep sea precipitation known as marine snow.

Marine snow also includes fish fecal pellets and other organic detritus, and steadily falls thousands of meters below active plankton blooms.

Evaluation of the biological effects and verification of the amount of carbon actually sequestered by any particular bloom involves a variety of measurements, combining ship-borne and remote sampling, submarine filtration traps, tracking buoy spectroscopy and satellite telemetry.

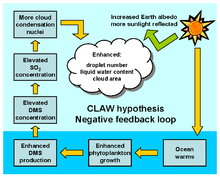

Some species of plankton produce dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a portion of which enters the atmosphere where it is oxidized by hydroxyl radicals (OH), atomic chlorine (Cl) and bromine monoxide (BrO) to form sulfate particles, and potentially increase cloud cover.

[139] Iron fertilization is relatively inexpensive compared to scrubbing, direct injection and other industrial approaches, and can theoretically sequester for less than €5/ton CO2, creating a substantial return.

[143] While ocean iron fertilization could represent a potent means to slow global warming, there is a current debate surrounding the efficacy of this strategy and the potential adverse effects of this.

Critics are concerned that fertilization will create harmful algal blooms (HAB) as many toxic algae are often favored when iron is deposited into the marine ecosystem.

Nitrogen released by cetaceans and iron chelate are a significant benefit to the marine food chain in addition to sequestering carbon for long periods of time.

[61] John Gribbin was the first scientist to publicly suggest that climate change could be reduced by adding large amounts of soluble iron to the oceans.

Environmental scientist Andrew Watson analyzed global data from that eruption and calculated that it deposited approximately 40,000 tons of iron dust into oceans worldwide.

The resolution states that ocean fertilization activities, other than legitimate scientific research, "should be considered as contrary to the aims of the Convention and Protocol and do not currently qualify for any exemption from the definition of dumping".

[155] An Assessment Framework for Scientific Research Involving Ocean Fertilization, regulating the dumping of wastes at sea (labeled LC-LP.2(2010)) was adopted by the Contracting Parties to the Convention in October 2010 (LC 32/LP 5).