Marine coastal ecosystem

For example, estuaries are areas where freshwater rivers meet the saltwater of the ocean, creating an environment that is home to a wide variety of species, including fish, shellfish, and birds.

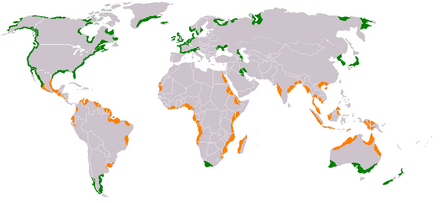

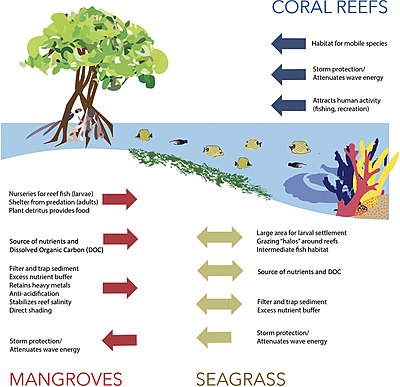

Mangrove forests survive in the intertidal zones of tropical or subtropical coasts, populated by salt-tolerant trees that protect habitat for many marine species, including crabs, shrimp, and fish.

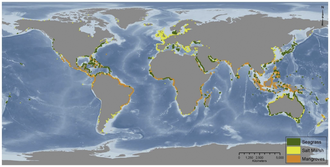

These meadows are underwater grasslands populated by marine flowering plants that provide nursery habitats and food sources for many fish species, crabs and sea turtles, as well as dugongs.

These are dominated by a large brown algae called kelp, a type of seaweed that grows several meters tall, creating dense and complex underwater forests.

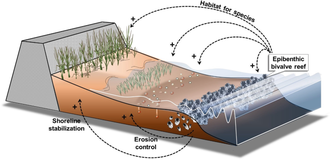

[17] Estuaries also provide essential ecosystem services such as water filtration, habitat protection, erosion control, gas regulation nutrient cycling, and it even gives education, recreation and tourism opportunities to people.

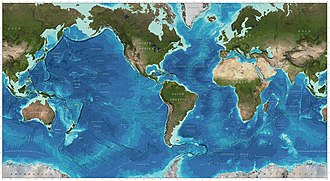

[20] Lagoons can be found in on coasts all over the world, on every continent except Antarctica and is an extremely diverse habitat being home to a wide array of species including birds, fish, crabs, plankton and more.

[26][25] Vegetated coastal ecosystems typically reside over organic-rich sediments that may be several meters deep and effectively lock up carbon due to low-oxygen conditions and other factors that inhibit decomposition at depth.

[28][29] When coastal habitats are degraded or converted to other land uses, the sediment carbon is destabilised or exposed to oxygen, and subsequent increased microbial activity releases large amounts of greenhouse gasses to the atmosphere or water column.

[63][64] The implementation of marine protected areas is one management strategy useful for addressing such issues, since it may limit the impacts of fishing and buffer the ecosystem from additive effects of other environmental stressors.

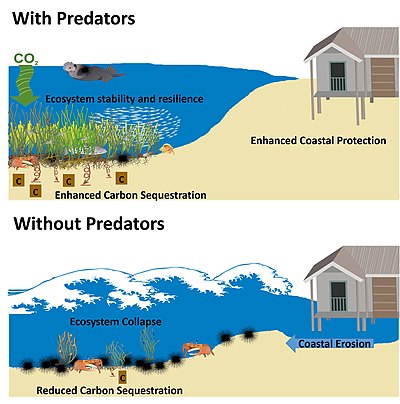

In coastal plant communities, such as kelp, seagrass meadows, mangrove forests and salt marshes, several studies have documented the far-reaching effects of changing predator populations.

Multiple examples have shown that changes to the strength or direction of predator effects on lower trophic levels can influence coastal erosion,[112] carbon sequestration,[113][114] and ecosystem resilience.

[119][120][121] Rapid advances in geospatial technologies and the proliferation of sensors, both above and below the ocean surface, have revealed intricate and scientifically intriguing ecological patterns and processes,[122][123][124] some of which are the result of human activities.

[125][126] Despite progress in the collecting, mapping, and sharing of ocean data, the gap between technological advances and the ability to generate ecological insights for marine management and conservation practice remains substantial.

[128] Deeper understanding of the multi-scale linkages between ecological structure, function, and change will better support the design of whole-system strategies for biodiversity preservation and reduce uncertainty around the consequences of human activity.

For example, in the design and evaluation of marine protected areas (MPAs) and habitat restoration, it is important to understand the influence of spatial context, configuration, and connectivity, and to consider effects of scale.

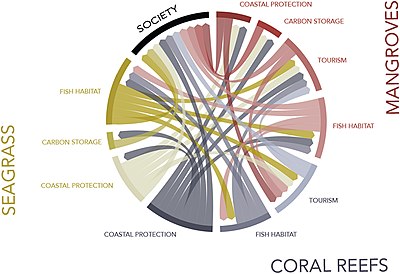

Regions where systems strongly intersect include Central America (Belize), the Caribbean, the Red Sea, the Coral Triangle (particularly Malaysia), Madagascar, and the Great Barrier Reef.

[136] To compound things, removal of biomass from the ocean occurs simultaneously with multiple other stressors associated to climate change that compromise the capacity of these socio-ecological systems to respond to perturbations.

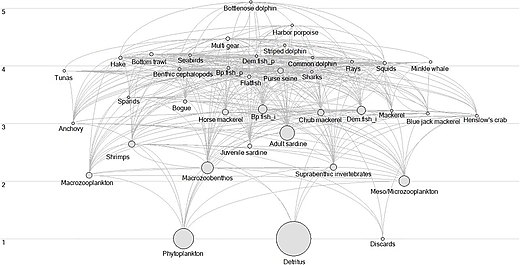

Plankton contributes approximately half of the global primary production, supports marine food webs, influences the biogeochemical process in the ocean, and strongly affects commercial fisheries.

[142][148][151] Long-term increases and decreases in plankton productivity have already occurred over the past two decades[152][153] along extensive regions of the Humboldt upwelling ecosystem off Chile, and are expected to propagate up the pelagic and benthic food webs.

[173] Eutrophication in coastal areas leads to shifts toward rapidly growing opportunistic algae, and generally to a decline in benthic macrovegetation because of decreased light penetration, substrate change and more reducing sediments.

[176][177] Hypoxic systems tend to lose many long-lived higher organisms and biogeochemical cycles typically become dominated by benthic bacterial processes and rapid pelagic turnover.

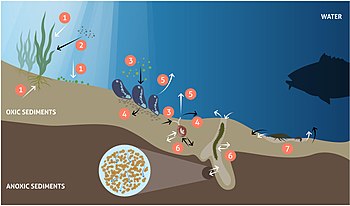

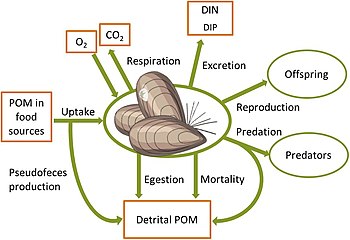

In the illuminated zone, benthic microphytes and macrophytes mediate biogeochemical fluxes through primary production, nutrient storage and sediment stabilization and act as a habitat and food source for a variety of animals, as shown in the diagram on the left above.

[194][195][196][197][137] Chile has been one of the countries implementing Territorial Use Rights (TURFs)[198][199] over an unprecedented geographic scale to manage the diverse coastal benthic resources using a co-management strategy.

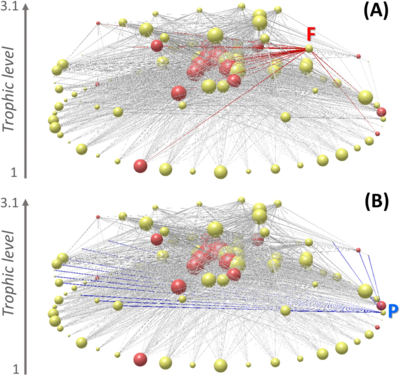

[207][208][209] It is imperative to improve understanding of the effects of these multi-species artisanal fisheries which simultaneously harvest species at all trophic levels from kelp primary producers to top carnivores.

[212] Essential elements of such distributed observation systems are the use of machine-to-machine communication, data fusion and processing applying recent technological developments for the Internet of Things (IoT) toward a common cyberinfrastructure.

[233] Normally, regime shifts are defined as high amplitude, low-frequency and often abrupt changes in species abundance and community composition that are observed at multiple trophic levels (TLs).

For example, almost 10% of the entire Great Barrier Reef coastline in Australia (2,300 km) has been replaced with urban infrastructure (e.g., rock seawalls, jetties, marinas), causing massive loss and fragmentation of sensitive coastal ecosystems.

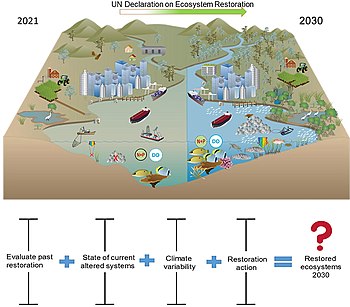

This call to action has the purpose of recognising the need to massively accelerate global restoration of degraded ecosystems, to fight the climate heating crisis, enhance food security, provide clean water and protect biodiversity on the planet.

[270][268] There has recently been a perceptual shift away from habitat representation as the sole or primary focus of conservation prioritisation, towards consideration of ecological processes that shape the distribution and abundance of biodiversity features.

[290][284] There is clear empirical evidence that proximity to nursery habitats can enhance the effectiveness (i.e. increasing the abundance, density, or biomass of fish species) of marine protected areas on coral reefs.