Smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat and a chemical reducing agent to an ore to extract a desired base metal product.

[1] It is a form of extractive metallurgy that is used to obtain many metals such as iron, copper, silver, tin, lead and zinc.

Smelting uses heat and a chemical reducing agent to decompose the ore, driving off other elements as gases or slag and leaving the metal behind.

[1] The oxygen in the ore binds to carbon at high temperatures, as the chemical potential energy of the bonds in carbon dioxide (CO2) is lower than that of the bonds in the ore. Sulfide ores such as those commonly used to obtain copper, zinc or lead, are roasted before smelting in order to convert the sulfides to oxides, which are more readily reduced to the metal.

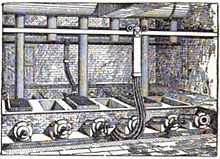

Smelting most prominently takes place in a blast furnace to produce pig iron, which is converted into steel.

A reducing environment (often provided by carbon monoxide, made by incomplete combustion in an air-starved furnace) pulls the final oxygen atoms from the raw metal.

The carbon source acts as a chemical reactant to remove oxygen from the ore, yielding the purified metal element as a product.

After successive interactions with carbon monoxide, all of the oxygen in the ore will be removed, leaving the raw metal element (e.g.

Fuel is burned at one end to melt the dry sulfide concentrates (usually after partial roasting) which are fed through openings in the roof of the furnace.

[12][13] A mace head found in Turkey and dated to 5000 BC, once thought to be the oldest evidence, now appears to be hammered, native copper.

Metals were hard enough to make weapons that were heavier, stronger, and more resistant to impact damage than wood, bone, or stone equivalents.

For several millennia, bronze was the material of choice for weapons such as swords, daggers, battle axes, and spear and arrow points, as well as protective gear such as shields, helmets, greaves (metal shin guards), and other body armor.

Bronze also supplanted stone, wood, and organic materials in tools and household utensils—such as chisels, saws, adzes, nails, blade shears, knives, sewing needles and pins, jugs, cooking pots and cauldrons, mirrors, and horse harnesses.

[citation needed] Tin and copper also contributed to the establishment of trade networks that spanned large areas of Europe and Asia and had a major effect on the distribution of wealth among individuals and nations.

[citation needed] The earliest known cast lead beads were thought to be in the Çatalhöyük site in Anatolia (Turkey), and dated from about 6500 BC.

However, tin and lead can be smelted by placing the ores in a wood fire, leaving the possibility that the discovery may have occurred by accident.

It is too soft to use for structural elements or weapons, though its high density relative to other metals makes it ideal for sling projectiles.

The earliest evidence for iron-making is a small number of iron fragments with the appropriate amounts of carbon admixture found in the Proto-Hittite layers at Kaman-Kalehöyük and dated to 2200–2000 BC.

Smelting has serious effects on the environment, producing wastewater and slag and releasing such toxic metals as copper, silver, iron, cobalt, and selenium into the atmosphere.

Lakes will likely receive mercury contamination from the smelter for decades, from both re-emissions returning as rainwater and leaching of metals from the soil.

[27] Air pollutants generated by aluminium smelters include carbonyl sulfide, hydrogen fluoride, polycyclic compounds, lead, nickel, manganese, polychlorinated biphenyls, and mercury.

[31][32][33] Wastewater pollutants discharged by iron and steel mills includes gasification products such as benzene, naphthalene, anthracene, cyanide, ammonia, phenols and cresols, together with a range of more complex organic compounds known collectively as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH).

[37] Labourers working in the smelting industry have reported respiratory illnesses inhibiting their ability to perform the physical tasks demanded by their jobs.