Electric Smelting and Aluminum Company

The businesses of the era dramatically increased the supply of aluminium, a valuable element not found in nature in pure form, and reduced its price.

The Cowles process was the immediate predecessor to the Hall-Héroult process—today in nearly universal use more than a century after it was discovered by Charles Martin Hall and Paul Héroult and adapted by others including Carl Josef Bayer.

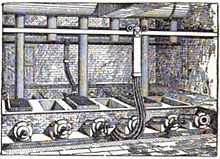

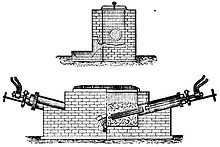

The Cowles furnace was electrochemical, one of two kinds of processes applied to producing aluminum during the 19th century, and belonged to the electrothermic group that includes Héroult (alloys), Brin, Bessemer, Stephanite and Moissan (carbide).

Minet thought Cowles was the first great advance in electrometallurgy at least for many years, calling it a "practical" furnace yielding alloy up to 20 percent aluminum.

The judge announced his decision in January 1893, finding them to be infringing the patent of Hall and having gained knowledge of his process by hiring away a chemist named Hobbs who was the foreman in Pittsburgh.

[citation needed] The surviving brother Alfred chose to stop work on aluminum and Cowles received royalties and a US$1.35 million payment in settlement.

[16][17] Cowles engineered a separate venture and did not share that glory, but sometimes the brothers are credited with envisioning and promoting what was the beginning of electrical smelting on a large scale.