Conservative vector field

[1] A conservative vector field has the property that its line integral is path independent; the choice of path between two points does not change the value of the line integral.

A conservative vector field is also irrotational; in three dimensions, this means that it has vanishing curl.

An irrotational vector field is necessarily conservative provided that the domain is simply connected.

Conservative vector fields appear naturally in mechanics: They are vector fields representing forces of physical systems in which energy is conserved.

In a two- and three-dimensional space, there is an ambiguity in taking an integral between two points as there are infinitely many paths between the two points—apart from the straight line formed between the two points, one could choose a curved path of greater length as shown in the figure.

However, in the special case of a conservative vector field, the value of the integral is independent of the path taken, which can be thought of as a large-scale cancellation of all elements

To visualize this, imagine two people climbing a cliff; one decides to scale the cliff by going vertically up it, and the second decides to walk along a winding path that is longer in length than the height of the cliff, but at only a small angle to the horizontal.

M. C. Escher's lithograph print Ascending and Descending illustrates a non-conservative vector field, impossibly made to appear to be the gradient of the varying height above ground (gravitational potential) as one moves along the staircase.

The force field experienced by the one moving on the staircase is non-conservative in that one can return to the starting point while ascending more than one descends or vice versa, resulting in nonzero work done by gravity.

On a real staircase, the height above the ground is a scalar potential field: one has to go upward exactly as much as one goes downward in order to return to the same place, in which case the work by gravity totals to zero.

This suggests path-independence of work done on the staircase; equivalently, the force field experienced is conservative (see the later section: Path independence and conservative vector field).

and the last equality holds due to the path independence

In other words, if it is a conservative vector field, then its line integral is path-independent.

This holds as a consequence of the definition of a line integral, the chain rule, and the second fundamental theorem of calculus.

Since the gradient theorem is applicable for a differentiable path, the path independence of a conservative vector field over piecewise-differential curves is also proved by the proof per differentiable curve component.

is a continuous vector field which line integral is path-independent.

over an arbitrary path between a chosen starting point

Let's choose the path shown in the left of the right figure where a 2-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system is used.

By the path independence, its partial derivative with respect to

A similar approach for the line integral path shown in the right of the right figure results in

This proof method can be straightforwardly expanded to a higher dimensional orthogonal coordinate system (e.g., a 3-dimensional spherical coordinate system) so the converse statement is proved.

(continuously differentiable) vector field, with an open subset

is a simply connected open space (roughly speaking, a single piece open space without a hole within it), the converse of this is also true: Every irrotational vector field in a simply connected open space

Say again, in a simply connected open region, an irrotational vector field

More abstractly, in the presence of a Riemannian metric, vector fields correspond to differential

, any exact form is closed, so any conservative vector field is irrotational.

For a two-dimensional field, the vorticity acts as a measure of the local rotation of fluid elements.

The vorticity does not imply anything about the global behavior of a fluid.

For conservative forces, path independence can be interpreted to mean that the work done in going from a point

is independent of the moving path chosen (dependent on only the points

-

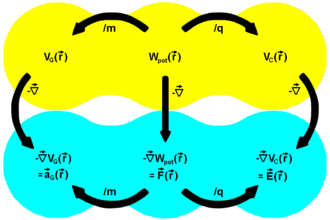

Scalar fields, scalar potentials:

- V G , gravitational potential

- W pot , (gravitational or electrostatic) potential energy

- V C , Coulomb potential

-

Vector fields, gradient fields:

- a G , gravitational acceleration

- F , (gravitational or electrostatic) force

- E , electric field strength