Bal des Ardents

The circumstances of the fire undermined confidence in the king's capacity to rule; Parisians considered it proof of courtly decadence and threatened to rebel against the more powerful members of the nobility.

Scholars believe the dance performed at the ball had elements of traditional charivari,[3] with the dancers disguised as wild men, mythical beings often associated with demonology, that were commonly represented in medieval Europe and documented in revels of Tudor England.

[note 2][4] Within two years, one of his uncles, Philip of Burgundy, described by historian Robert Knecht as "one of the most powerful princes in Europe",[5] became sole regent to the young king after Louis of Anjou pillaged the royal treasury and departed to campaign in Italy.

Convinced that the attempt on Clisson's life was also an act of violence against himself and the monarchy, Charles quickly planned a retaliatory invasion of Brittany with the approval of the Marmousets, and within months departed Paris with a force of knights.

[6][7] On a hot August day outside Le Mans, accompanying his forces on the way to Brittany, Charles drew his weapons without warning and charged his own household knights including his brother Louis I, Duke of Orléans—with whom he had a close relationship—crying, "Forward against the traitors!

"[11] During the worst of his illness the king was unable to recognize his wife, Isabeau of Bavaria, demanding her removal when she entered his chamber, but after his recovery he made arrangements for her to hold guardianship of their children.

[12] In A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century, the historian Barbara Tuchman writes that the physician Harsigny, refusing "all pleas and offers of riches to remain,"[13] left Paris and ordered the courtiers to shield Charles VI from the duties of government and leadership.

Isabeau and her sister-in-law Valentina Visconti, Duchess of Orléans, wore jewel-laden dresses and elaborate braided hairstyles coiled into tall shells and covered with wide double hennins that reportedly required doorways to be widened to accommodate them.

[2][note 3] Tuchman explains that a widow's remarriage was traditionally an occasion for mockery and tomfoolery, often celebrated with a charivari characterized by "all sorts of licence, disguises, disorders, and loud blaring of discordant music and clanging of cymbals".

[3] On the suggestion of Huguet de Guisay, whom Tuchman describes as well known for his "outrageous schemes" and cruelty, six young men, including Charles, performed a dance in costume as wood savages.

[1] The event was chronicled in uncharacteristic vividness by the Monk of St Denis, who wrote that "four men were burned alive, their flaming genitals dropping to the floor ... releasing a stream of blood".

The instigator of the affair, Huguet de Guisay, survived a day longer, described by Tuchman as bitterly "cursing and insulting his fellow dancers, the dead and the living, until his last hour.

"[21] Orléans' reputation was severely damaged by the event, compounded by an episode a few years earlier in which he was accused of sorcery after hiring an apostate monk to imbue a ring, dagger and sword with demonic magic.

The theologian Jean Petit later testified that Orléans practiced sorcery, and that the fire at the dance represented a failed attempt at regicide made in retaliation for Charles' attack the previous summer.

[23] In 1407, Philip of Burgundy's son, John the Fearless, had his cousin Orléans assassinated because of "vice, corruption, sorcery, and a long list of public and private villainies"; at the same time Isabeau was accused of having been the mistress of her husband's brother.

The vacuum created by the lack of central power and the general irresponsibility of the French court resulted in it gaining a reputation for lax morals and decadence that endured for more than 200 years.

[25] Veenstra writes in Magic and Divination at the Courts of Burgundy and France that the Bal des Ardents reveals the tension between Christian beliefs and the latent paganism that existed in 14th-century society.

[26] Common superstition held that long-haired wild men, known as lutins, who danced to firelight either to conjure demons or as part of fertility rituals, lived in mountainous areas such as the Pyrenees.

In some village charivaris at harvest or planting time dancers dressed as wild men, to represent demons, were ceremonially captured and then an effigy of them was symbolically burnt to appease evil spirits.

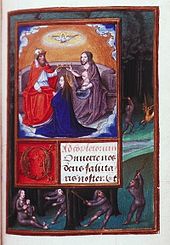

[27] The death of four members of the French nobility was sufficiently important to ensure that the event was recorded in contemporary chronicles, most notably by Froissart and the Monk of St Denis, and subsequently illustrated in copies of illuminated manuscripts.

[30][36] The monk's chronicle is generally accepted as essential for understanding the king's court, however his neutrality may have been affected by his pro-Burgundian and anti-Orléanist stance, causing him to depict the royal couple in a negative manner.