Dynasty of Isin

While there was no outright conflict, Ishbi-Erra continued to extend his influence as Ibbi-Sin's steadily declined over the next 12 years or so, until Ur was finally conquered by Kindattu of Elam.

Some years later, Ishbi-Erra ousted the Elamite garrison from Ur, thereby asserting suzerainty over Sumer and Akkad, celebrated in one of his later 27th year-name, although this specific epithet was not used by this dynasty until the reign of Iddin-Dagan.

[3] He readily adopted the regal privileges of the former regime, commissioning royal praise poetry and hymns to deities, of which seven are extant, and proclaiming himself Dingir-kalam-ma-na, “a god in his own country.”[i 4] He appointed his daughter, En-bara-zi, to succeed that of Ibbi-Sin's as Egisitu-priestess of An, celebrated in his 22nd year-name.

Šu-ilišu built a monumental gateway and recovered an idol representing Ur's patron deity (Nanna, god of the moon) which had been expropriated by the Elamites when they sacked the city-state, but; whether he obtained it either through diplomacy or conflict is unknown.

Kindattu had been driven away from the city-state of Ur by Išbi-Erra[i 14] (the founder of the First Dynasty of Isin), however; relations had apparently thawed sufficiently for Tan-Ruhurarter (the 8th king to wed the daughter of Bilalama, the énsí of Eshnunna.

A fragment of a stone statue[i 15] has a votive inscription which invokes Ninisina and Damu to curse those who foster evil intent against it.

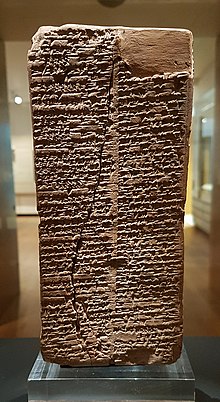

2 later clay tablet copies[i 16] of an inscription recording an unspecified object fashioned for the god Nanna were found by the British archaeologist Sir Charles Leonard Woolley in a scribal school house in the city-state of Ur.

A tablet[i 18] described Iddin-Dagān's fashioning of two copper festival statues for Ninlil, which were not delivered to Nippur until 170 years later by Enlil-bāni.

The continued fecundity of the land was ensured by the annual performance of the sacred marriage ritual in which the king impersonated Dumuzi-Ama-ušumgal-ana and a priestess substituted for the part of Inanna.

According to the šir-namursaḡa, the hymn composed describing it in 10 sections (Kiruḡu), this ceremony seems to have entailed the procession of: male prostitutes, wise women, drummers, priestesses and priests bloodletting with swords, to the accompaniment of music, followed by offerings and sacrifices for the goddess Inanna, or Ninegala.

His year-name “year (Ur-Ninurta) set for Enlil free (of forced labor) for ever the citizens of Nippur and released (the arrears of) the taxes which they were bearing on their necks” may mark this point.

His offensive was stopped at Adab, modern Bismaya, where Abī-sarē “defeated the army of Isin with his weapon,” in the 9th year-name of his reign.

Lu-Inanna, a nišakku priest was murdered by Nanna-sig, Ku-Enlilla (a barber) and Enlil-ennam (an orchard-keeper) who then confessed to his estranged wife, Nin-dada, who remained suspiciously silent on the matter.

[22] The Instructions of Ur-Ninurta and Counsels of Wisdom is a Sumerian courtly composition which extols the virtues of the king, the reestablisher of order, justice and cultic practices after the flood in emulation of the older role models Gilgamesh and Ziusudra.

The titles “shepherd who makes Nippur content,” "mighty farmer of Ur," “who restores the designs for Eridu” and “en priest for the mes, for Uruk” were used by Bur-Suen in his standard brick inscriptions in Nippur and Isin,[i 25] although it seems unlikely that his rule stretched to Ur or Eridu at this time as the only inscriptions with an archaeological provenance come from the two northerly cities.

This latter king's year-names record victories over Akusum, Kazallu, Uruk (which had seceded from Isin), Lugal-Sîn, Ka-ida, Sabum, Kiš, and village of Nanna-isa, relentlessly edging north and feverish activity digging canals or filling them in, possibly to counter the measures taken by Bur-Suen to contain him.

He seized control of Kisurra for a time as two year-names are found among tablets from this city, possibly following the departure of Sumu-abum the king of Babylon who “returned to his city.” The occupation was brief, however, as Sumu-El was to conquer it during his fourth year.

[30] His brief reign ended a period of relative stability and he was succeeded by Erra-Imittī whose filiation is unknown, as the SKL omits this information from this point on.

Both he and his successor were conspicuous in the absence of royal hymns or dedicatory prayers and Hallo speculates this may have been due to the distractions afforded by the commencement of conflict with Larsa.

[35] A haematite cylinder seal[i 30] of his servant and scribe Iliška-uṭul, son of Sîn-ennam, has come to light from this city, suggesting prolonged occupation.

A certain Ikūn-pî-Ištar[nb 9] is recorded as having ruled for 6 months or a year, between the reigns of Erra-imittī and Enlil-bani according to two variant copies of a chronicle.

Uruk, too, seceded during his reign and, as his power crumbled, he may have had the Chronicle of Early Kings[i 33] redacted to provide a more legendary tale of his accession than the rather mundane act of usurpation that it may well have been.

[39] The colophon of a medical text,[i 34] “when a man's brain contains fire,”[nb 10] from the Library of Ashurbanipal reads: “Proven and tested salves and poultices, fit for use, according to the old sages from before the flood[nb 11] from Šuruppak, which Enlil-muballiṭ, sage (apkallu) of Nippur, left (to posterity) in the second year of Enlil-bāni.”[40][41][42] Enlil-bani found it necessary to "build anew the wall of Isin which had become dilapidated,"[i 35] which he recorded on commemorative cones.

He was a prodigious builder, responsible for the construction of the é-ur-gi7-ra, “the dog house,”[i 37] temple of Ninisina, a palace,[i 38] also the é-ní-dúb-bu, “house of relaxation,” for the goddess Nintinugga, “lady who revives the dead,”[i 39] the é-dim-gal-an-na, “house - great mast of heaven,”[i 40] for the tutelary deity of Šuruppak, the goddess Sud, and finally, the é-ki-ág-gá-ni for Ninibgal, the “lady with patient mercy who loves ex-votos, who heeds prayers and entreaties, his shining mother.”[i 41][43] Two large copper statues were taken to Nippur for dedication to Ningal, which Iddin-Dagān had fashioned 117 years earlier but had been unable to deliver, “on account of this, the goddess Ninlil had the god Enlil lengthen the life span of Enlil-Bāni.”[i 42][44] There are perhaps two hymns addressed to this monarch.

[i 48][29] He was the third in a sequence of short reigning monarchs whose filiation was unknown and whose power extended over a small region encompassing little more than the city of Isin and its neighbor Nippur.

He credited Dāgan, a god from the middle Euphrates region who had possibly been introduced by the dynasty's founder, Išbi-Erra, with his creation, in cones[i 49] commemorating the construction of the deity's temple, the Etuškigara, or the house “well founded residence,” an event also celebrated in a year-name.

A cone shaft[i 51] memorializes the building of a temple of Lulal of the cultic city of Dul-edena, northeast of Nippur on the Iturungal canal.

One of the cones bearing this inscription was found in the ruins of the temple of Ninurta, the é-ḫur-sag-tí-la, in Babylon, and is thought likely to have been an ancient museum piece.

A province in the south and a town in eastern Babylonia near Tuplias are both called Bīt-Suen-magir and some historians have speculated one or other were named in his honor.

Four royal inscriptions are extant including cones celebrating the building of the wall of Isin, naming him as “Damiq-ilišu is the favorite of the god Ninurta” also recollected in a year-name and “suitable for the office of en priest befitting the goddess Inanna.”[i 60] Construction of a storehouse e-me-sikil, “house with pure mes (rites?