Sumerian King List

In the oldest known version, dated to the Ur III period (c. 2112 – c. 2004 BC) but probably based on Akkadian source material, the SKL reflected a more linear transition of power from Kish, the first city to receive kingship, to Akkad.

In its best-known and best-preserved version, as recorded on the Weld-Blundell Prism, the SKL begins with a number of fictional antediluvian kings, who ruled before a flood swept over the land, after which kingship went to Kish.

In the past, the Sumerian King List was considered as an invaluable source for the reconstruction of the political history of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia.

More recent research has indicated that the use of the SKL is fraught with difficulties, and that it should only be used with caution, if at all, in the study of ancient Mesopotamia during the third and early second millennium BC.

It should also be noted that the modern usage of the term dynasty, i.e. a sequence of rulers from a single family, does not necessarily apply to ancient Mesopotamia.

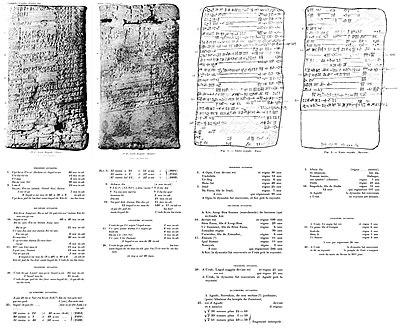

The so-called Ur III Sumerian King List (USKL), on a clay tablet possibly found in Adab, is the only known version of the SKL that predates the Old Babylonian period.

This pattern of cities receiving kingship and then falling or being defeated, only to be succeeded by the next, is present throughout the entire text, often in the exact same words.

Exceptions are Etana, "who ascended to heaven and consolidated all the foreign countries" and Enmebaragesi, "who made the land of Elam submit".

The next lines, up until Sargon of Akkad, show a steady succession of cities and kings, usually without much detail beyond the lengths of the individual reigns.

Lines 211–223 describe a dynasty from Mari, which is a city outside Sumer proper but which played an important role in Mesopotamian history during the late third and early second millennia BC.

Sargon of Akkad is mentioned in the Sumerian King List as cup-bearer to Ur-zababa of Kish, and he defeated Lugal-zage-si of Uruk before founding his own dynasty.

The Sumerian King List remarks that, after the rule of Ur was abolished, "The very foundation of Sumer was torn out", after which kingship was taken to Isin.

Piotr Steinkeller [de] has observed that, with the exception of the Epic of Gilgamesh, there might not be a single cuneiform text with as much "name recognition" as the Sumerian King List.

[4] All but one of the surviving versions of the Sumerian King List date to the Old Babylonian period, i.e. the early part of the second millennium BC.

[12][11][13] One version, the Ur III Sumerian King List (USKL) dates to the reign of Shulgi (2084–2037 BC).

The cyclical change of kingship from one city to the next became a so-called Leitmotif, or recurring theme, in the Sumerian King List.

In this way the Akkadian dynasty could legitimize its claims to power over Babylonia by arguing that, from the earliest times onwards, there had always been a single city where kingship was exercised.

This is why, for example, the version recorded on the Weld-Blundell prism ends with the Isin dynasty, suggesting that it was now their turn to rule over Mesopotamia as the rightful inheritors of the Ur III legacy.

[3][15] The use of the SKL as political propaganda may also explain why some versions, including the older USKL, did not contain the antediluvian part of the list.

[3] During much of the 20th century, many scholars accepted the Sumerian King List as a historical source of great importance for the reconstruction of the political history of Mesopotamia, despite the problems associated with the text.

[5][17][18] For example, many scholars have observed that the kings in the early part of the list reigned for unnaturally long time spans.

His solution to the reigns considered too long, then, was to argue that "[t]heir occurrence in our material must be ascribed to a tendency known also among other peoples of antiquity to form very exaggerated ideas of the length of human life in the earliest times of which they were conscious."

In order to create a fixed chronology where individual kings could be absolutely dated, Jacobsen replaced time spans considered too long with average reigns of 20–30 years.

[19] Others have attempted to reconcile the reigns in the Sumerian King List by arguing that many time spans were actually consciously invented, mathematically derived numbers.

For example, many recent handbooks on the archaeology and history of ancient Mesopotamia all acknowledge the problematic nature of the SKL and warn that the list's use as a historical document for that period is severely limited up to the point that it should not be used at all.

[12][21] Recent studies on the SKL even go so far as to discredit the composition as a valuable historical source on Early Dynastic Mesopotamia altogether.

Important arguments to dismiss the SKL as a reliable and valuable source are its nature as a political, ideological text, its long redactional history, and the fact that out of the many pre-Sargonic kings listed, only seven have been attested in contemporary Early Dynastic inscriptions.

Many of the rulers in the pre-Sargonic part (i.e. prior to Sargon of Akkad) of the list must therefore be considered as purely fictional or mythological characters to which reigns of hundreds of years were assigned.

For example, it has been noted that the king list is unique among Sumerian compositions in there being no divine intervention in the process of dynastic change.

Beginning with Lugal-zage-si and the Third Dynasty of Uruk (which was defeated by Sargon of Akkad), a better understanding of how subsequent rulers fit into the chronology of the ancient Near East can be deduced.