Cosmology in the Muslim world

The same motif is used in the Bible as well.References to heavens and earth constitute a literary device known as a merism, where two opposites or contrasting terms are used to refer to the totality of something.

Al-Razi in his Matalib al-'Aliya explores the possibility that a multiverse exists in his interpretation of the Qur'anic verse "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds."

Al-Razi decides that God is capable of creating as many universes as he wishes, and that prior arguments for assuming the existence of a single universe are weak:[15]It is established by evidence that there exists beyond the world a void without a terminal limit (khala' la nihayata laha), and it is established as well by evidence that God Most High has power over all contingent beings (al-mumkinat).

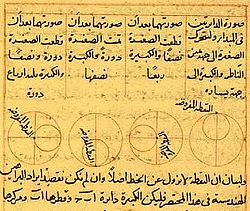

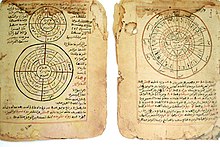

[17] ʿAjā'ib al-makhlūqāt wa gharā'ib al-mawjūdāt (Arabic: عجائب المخلوقات و غرائب الموجودات, meaning Marvels of creatures and Strange things existing) is an important work of cosmography by Zakariya ibn Muhammad ibn Mahmud Abu Yahya al-Qazwini who was born in Qazwin year 600 (AH (1203 AD).

His views were adopted and elaborated in many forms by medieval Jewish and Islamic thinkers, including Saadia Gaon among the former and figures like Al-Kindi and Al-Ghazali among the latter.

[23] Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya (1292–1350) spent over two hundred pages of his Miftah Dar al-SaCadah refuting the practices of divination, especially in the form of astrology and alchemy.

The primary purpose of the work was to help explicate Ptolemy's, but it also included some corrections based on the findings of earlier Arab astronomers.

Al-Farghani gave revised values for the obliquity of the ecliptic, the precessional movement of the apogees of the Sun and the Moon, and the circumference of the Earth.

The findings were compiled into a book called al-Zij al-Mumtahan ("The verified tables"), which is widely quoted in later astronomers but itself no longer extant.

"[26] The Persian astronomer Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī (973–1048) proposed the Milky Way galaxy to be "a collection of countless fragments of the nature of nebulous stars.

"[27] The Andalusian astronomer Ibn Bajjah ("Avempace", d. 1138) proposed that the Milky Way was made up of many stars which almost touched one another and appeared to be a continuous image due to the effect of refraction from sublunary material, citing his observation of the conjunction of Jupiter and Mars on 500 AH (1106/1107 AD) as evidence.

[24] In the 10th century, the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi (known in the West as Azophi) made the earliest recorded observation of the Andromeda Galaxy, describing it as a "small cloud".

The Hellenistic Greek astronomer Seleucus of Seleucia, who advocated a heliocentric model in the 2nd century BC, wrote a work that was later translated into Arabic.

We, too, have composed a book on the subject called Miftah 'ilm al-hai'ah (Key of Astronomy), in which we think we have surpassed our predecessors, if not in the words, at all events in the matter.

"Ibn al-Haytham (Latinized as Alhazen) wrote a work in the hay'a tradition of Islamic astronomy known as Al-Shukūk ‛alà Baṭlamiyūs (Doubts on Ptolemy).

[36] Ibn al-Haytham developed a physical structure of the Ptolemaic system in his Treatise on the configuration of the World, or Maqâlah fî hay'at al-‛âlam, which became an influential work in the hay'a tradition.

[43] In 1030, Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī discussed the Indian planetary theories of Aryabhata, Brahmagupta and Varahamihira in his Ta'rikh al-Hind (Latinized as Indica).

"In 1984, Abdelhamid Sabra coined the term "Andalusian Revolt" to describe an event beginning among twelfth century astronomers in al-Andalus where mounting discomfort over the conflicts between theory and observation resulted in astronomers transitioning away from the unquestioned authority of Ptolemy to rejecting his theory in favor of radically different solutions.

I have not heard it from his pupils; and even if it be correct that he discovered such a system, he has not gained much by it, for eccentricity is likewise contrary to the principles laid down by Aristotle....

I have explained to you that these difficulties do not concern the astronomer, for he does not profess to tell us the existing properties of the spheres, but to suggest, whether correctly or not, a theory in which the motion of the stars and planets is uniform and circular, and in agreement with observation.

[28] Later in the 12th century, his successors Ibn Tufail and Nur Ed-Din Al Betrugi (Alpetragius) were the first to propose planetary models without any equant, epicycles or eccentrics.

Like their Andalusian predecessors, the Maragha astronomers attempted to solve the equant problem and produce alternative configurations to the Ptolemaic model.

[61] Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī (1201–1274) resolved significant problems in the Ptolemaic system by developing the Tusi-couple as an alternative to the physically problematic equant introduced by Ptolemy for every planet except Mercury.

Supporters of this theory included Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī, Nizam al-Din al-Nisaburi (c. 1311), al-Sayyid al-Sharif al-Jurjani (1339–1413), Ali Qushji (d. 1474), and Abd al-Ali al-Birjandi (d. 1525).

[54] In the early 11th century, Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) wrote the Maqala fi daw al-qamar (On the Light of the Moon) some time before 1021.

Ibn al-Haytham had "formulated a clear conception of the relationship between an ideal mathematical model and the complex of observable phenomena; in particular, he was the first to make a systematic use of the method of varying the experimental conditions in a constant and uniform manner, in an experiment showing that the intensity of the light-spot formed by the projection of the moonlight through two small apertures onto a screen diminishes constantly as one of the apertures is gradually blocked up.

Al-Razi himself remains "undecided as to which celestial models, concrete or abstract, most conform with external reality," and notes that "there is no way to ascertain the characteristics of the heavens," whether by "observable" evidence or by authority (al-khabar) of "divine revelation or prophetic traditions."

He concludes that "astronomical models, whatever their utility or lack thereof for ordering the heavens, are not founded on sound rational proofs, and so no intellectual commitment can be made to them insofar as description and explanation of celestial realities are concerned.

"[65] The theologian Adud al-Din al-Iji (1281–1355), under the influence of the Ash'ari doctrine of occasionalism, which maintained that all physical effects were caused directly by God's will rather than by natural causes, rejected the Aristotelian principle of an innate principle of circular motion in the heavenly bodies,[66] and maintained that the celestial spheres were "imaginary things" and "more tenuous than a spider's web".

[67] His views were challenged by al-Jurjani (1339–1413), who argued that even if the celestial spheres "do not have an external reality, yet they are things that are correctly imagined and correspond to what [exists] in actuality".