Shia Islamism

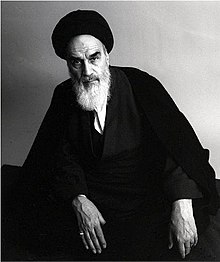

Historian Ervand Abrahamian argues that Khomeini and his Islamist movement not only created a new form of Shiism, but converted traditional Shi'ism "from a conservative quietist faith" into "a militant political ideology that challenged both the imperial powers and the country's upper class".

[21] Some major tenants of Twelver Shīʿa Muslim belief are Traditionally, the term Shahid in Shi'ism referred to "the famous Shi'i saints who in obeying God's will, had gone to their deaths",[27] such as the "Five Martyrs".

[29] While waiting for his return and rule, Shia jurists have tended to stick to one of three approaches to the state, according to at least two historians (Moojan Momen, Ervand Abrahamian): cooperated with it, trying to influence policies by becoming active in politics, or most commonly, remaining aloof from it.

[30][31][note 3] For many centuries prior to the spread of Khomeini's book, "no Shii writer ever explicitly contended that monarchies per se were illegitimate or that the senior clergy had the authority to control the state."

They were also to use reason to update these laws; issue pronouncements on new problems; adjudicate in legal disputes; and distribute the khoms contributions to worthy widows, orphans, seminary students, and indigent male descendants of the Prophet.

[34] Prior to 1970 Khomeini "emphasized that no cleric had ever claimed the right to rule; that many, including Majlisi, had supported their rulers, participated in government, and encouraged the faithful to pay taxes and cooperate with state authorities.

[43][44] Following "in the footsteps" of Ali Shariati, the Tudeh Party, Mojahedin, Hojjat al-Islam Nimatollah Salahi-Najafabadi, by the 1970s Khomeini began to embrace the idea that martyrdom was "not a saintly act, but a revolutionary sacrifice to overthrow a despotic political order".

[47] accused him of widening the gap between rich and poor; favoring cronies, relatives ... wasting oil resources on the ever expanding army and bureaucracy ... condemning the working class to a life of poverty, misery, and drudgery ... neglecting low-income housing", dependency on the west, supporting the US and Israel, undermining Islam and Iran with "cultural imperialism",[54] "I should state that the government, which is part of the absolute deputyship of the Prophet, is one of the primary injunctions of Islam and has priority over all other secondary injunctions, even prayers, fasting and hajj.

[69] Not as successful was Tehran's post-revolutionary "money and organizational help" in other countries, first to create Shia militias and revolutionary groups to spread Islamic revolution, and following that to encourage "armed conflicts, street protests and rebellion, and acts of terrorism" against secular and pro-American regimes such as Egypt and Pakistan.

[70] Ayatullah Khomeini's manifesto Islamic Government, Guardianship of the jurist, was greatly influenced by Rida's book (Persian: اسلام ناب) and by his analysis of the post-colonial Muslim world.

[71] Before the Islamic Revolution, Ali Khamenei, the man who is today's Supreme Leader of Iran, was an early champion and translator of the works of the Brotherhood jihadist theorist, Sayyid Qutb.

[72] Other Sunni Islamists/revivalists who were translated into Persian include Sayyid's brother, Muhammad Qutb, and South Asian Islamic revivalist writer Abul A'la Maududi along with other Pakistani and Indian Islamists.

[85] Saudi Arabia served as a leader of Sunni fundamentalism, but Khomeini saw monarchy as unislamic and the House of Saud as "unpopular and corrupt"—dependent on American protection, and ripe for overthrow,[86] just as the shah had been.

Financial and geographic independence (Najaf and Karbala were outside the borders of the Iranian Empire); the right to interpretation, even to innovation on all questions; delegitimization of the state ... ; strong hierarchy and structure; all operated to make the clergy a political force.

The Sandinistas, African National Congress, and Irish Republican Army, were promoted over neighboring Sunni Muslims in Afghanistan, who though fighting invading atheist Russians, were politically conservative.

This gave its ulama "historical autonomy vis-à-vis the state", which allowed it to escape cooptation by Sunni rulers and thus "able to engage with contemporary problems and stay relevant", through the practice of ijtihad in divine law.

Other theories are that the idea is not at all new, but has been accepted by knowledgeable Shia faqih since medieval times, but kept from the general public by taqiya (precautionary dissimulation) (Ahmed Vaezi);[111] that it was "occasionally" interpreted during the reign of the Safavid dynasty (1501–1702 C.E.)

[114] Developments that might be called steps easing the path to theocratic rule were the 16th-century rise of the Safavid dynasty over modern day Iran which made Twelver Shi'ism the state religion and belief compulsory;[115][116] and in the late 18th century the triumph of the Usuli school of doctrine over the Akhbari.

The latter change made the ulama "the primary educators" of society, dispensers mostly of the justice, overseers social welfare, and collectors of its funding (the zakat and khums religious taxes, managers of the "huge" waqf mortmains and other properties), and generally in control of activities that in modern states are left to the government.

Al-e-Ahmad "was the only contemporary writer ever to obtain favorable comments from Khomeini", who wrote in a 1971 message to Iranian pilgrims on going on Hajj,"The poisonous culture of imperialism [is] penetrating to the depths of towns and villages throughout the Muslim world, displacing the culture of the Qur'an, recruiting our youth en masse to the service of foreigners and imperialists..."[187]At least one historian (Ervand Abrahamian) speculates Al-e-Ahmad may have been an influence on Khomeini's turning away from traditional Shi'i thought towards populism, class struggle and revolution.

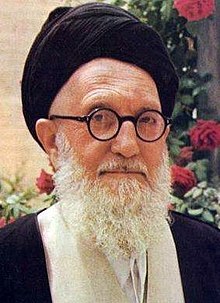

[193] Shariati was also a harsh critic of traditional Usuli clergy (including Ayatullah Hadi al-Milani), who he and other leftist Shia believed were standing in the way of the revolutionary potential of the masses,[194] by focusing on mourning and lamentation for the martyrs, awaiting the return of the messiah, when they should have been fighting "against the state injustice begun by Ali and Hussein".

Shari'ati was often anticlerical but Khomeini was able to "win over his followers by being forthright in his denunciations of the monarchy; by refusing to join fellow theologians in criticizing the Husseinieh-i Ershad; by openly attacking the apolitical and the pro-regime `ulama; by stressing such themes as revolution, anti-imperialism, and the radical message of Muharram; and by incorporating into his public declarations such `Fanonist` terms as the `mostazafin will inherit the earth`, `the country needs a cultural revolution,` and the `people will dump the exploiters onto the garbage heap of history.` [198] Shariati was also influenced by anti-democratic Islamist ideas of Muslim Brotherhood thinkers in Egypt and he tried to meet Muhammad Qutb while visiting Saudi Arabia in 1969.

[200] Ayatullah Hadi Milani, the influential Usuli Marja in Mashhad during the 1970s, had issued a fatwa prohibiting his followers from reading Ali Shariati's books and Islamist literature produced by young clerics.

[205] Qasim was overthrown in 1963, by the pan-Arabist Ba'ath party, but the crackdown on Shi'i religious centers continued, closing periodicals and seminaries, expelling non-Iraqi students from Najaf.

[207] a veteran in the struggle against the Pahlavi regime, he was imprisoned on several occasions over the decades, "as a young preacher, as a mid-ranking cleric, and as a senior religious leader just before the revolution,"[208] and served a total of a dozen years in prison.

Notes of the lectures were soon made into a book that appeared under three different titles: The Islamic Government, Authority of the Jurist, and A Letter from Imam Musavi Kashef al-Gita[214] (to deceive Iranian censors).

[219] In Isfahan, Ayatullah Khoei's representative Syed Abul Hasan Shamsabadi gave sermons criticizing the Islamist interpretation of Shi'i theology, he was abducted and killed by the notorious group called Target Killers (Persian: هدفی ها) headed by Mehdi Hashmi.

After a series of severe crack downs on the people and the clerics and the killing and arrest of many, Shariatmadari criticized the Shah's government and declared it non-Islamic, tacitly giving support to the revolution hoping that a democracy would be established in Iran.

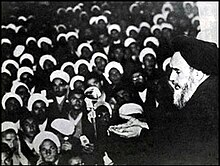

Mullahs who had hitherto withheld support from Khomeini and his doctrines "now fell in line", providing the resources of "over 20,000 properties and buildings throughout Iran", where Muslims "gathered to talk and receive orders".

[229] On 10 and 11 December 1978, the days of Tasu'a and Ashura, millions marched on the streets of Tehran, chanting ‘Death to Shah’, a display that political scientist Gilles Kepel has dubbed the "climax" of "general submission to Islamist cultural hegemony" in Iran.