Italian front (World War I)

Fighting along the front displaced much of the local population, and several thousand civilians died from malnutrition and illness in Kingdom of Italy and Austro-Hungarian refugee camps.

[9][10] However, if, in the course of events, the maintenance of the status quo in the regions of the Balkans or of the Ottoman coasts and islands in the Adriatic and in the Aegean Sea should become impossible, and if, whether in consequence of the action of a third Power or otherwise, Austria-Hungary or Italy should find themselves under the necessity of modifying it by a temporary or permanent occupation on their part, this occupation shall take place only after a previous agreement between the two Powers, based upon the principle of reciprocal compensation for every advantage, territorial or other, which each of them might obtain beyond the present status quo, and giving satisfaction to the interests and well-founded claims of the two Parties.

Taking into account the natural terrain, the many yokes, peaks and ridges with the resulting differences in height, the effective length was several thousand kilometers.

The barren landscape and lack of sufficient arable land led to little development of these high elevations; settlement was largely limited to the lower-lying zones.

From the Julian Alps to the Adriatic Sea, the mountains are constantly losing on height and only rarely reach 1,000 meters as in the area around Gorizia.

[20] FML Cletus Pichler, the chief of staff of the LVK Tirol, wrote: [21] A general attack on the most important penetration points, such as the Stilfser Joch, Etschtal, Valsugana, Rollepass [sic], [and] Kreuzbergpass, [...] could have led to significant enemy successes in view of the extremely weak defense forces in May.That the opportunity for a quick breakthrough was not used was partly due to the slow mobilization of the Italian army.

Due to the poorly developed transport network, the provision of troops and war material could only be completed in mid-June, i.e. a month later than estimated by the military leadership.

[26] At the opening of the campaign, Austro-Hungarian troops occupied and fortified high ground of the Julian Alps and Karst Plateau, but the Italians initially outnumbered their opponents three-to-one.

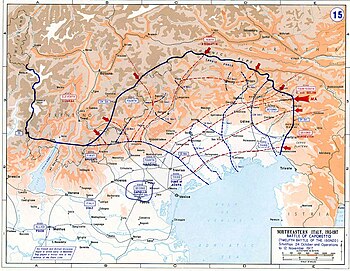

An Italian offensive aimed to cross the Soča (Isonzo) river, take the fortress town of Gorizia, and then enter the Karst Plateau.

At the beginning of the First Battle of the Isonzo on 23 June 1915, Italian forces outnumbered the Austrians three-to-one but failed to penetrate the strong Austro-Hungarian defensive lines in the highlands of northwestern Gorizia and Gradisca.

[26] Like most contemporaneous militaries, the Italian army primarily used horses for transport but struggled and sometimes failed to supply the troops sufficiently in the tough terrain.

In the northern section of the front, the Italians managed to overrun Mount Batognica over Kobarid (Caporetto), which would have an important strategic value in future battles.

Both sides suffered more casualties, but the Italians conquered important entrenchments, and the battle ended on 2 December for exhaustion of armaments, but occasional skirmishing persisted.

The Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth battles of the Isonzo (14 September – 4 November) managed to accomplish little except to wear down the already exhausted armies of both nations.

On 25 August, the Emperor Charles wrote to the Kaiser the following: "The experience we have acquired in the eleventh battle has led me to believe that we should fare far worse in the twelfth.

In order to protect their soldiers from enemy fire and the hostile alpine environment, both Austro-Hungarian and Italian military engineers constructed fighting tunnels which offered a degree of cover and allowed better logistics support.

Working at high altitudes in the hard carbonate rock of the Dolomites, often in exposed areas near mountain peaks and even in glacial ice, required extreme skill of both Austro-Hungarian and Italian miners.

In addition to building underground shelters and covered supply routes for their soldiers like the Italian Strada delle 52 Gallerie, both sides also attempted to break the stalemate of trench warfare by tunneling under no man's land and placing explosive charges beneath the enemy's positions.

Characteristic of nearly every other theater of the war, the Italians found themselves on the verge of victory but could not secure it because their supply lines could not keep up with the front-line troops and they were forced to withdraw.

However, the Italians despite suffering heavy casualties had almost exhausted and defeated the Austro-Hungarian army on the front, forcing them to call in German help for the much anticipated Caporetto Offensive.

The Austro-Hungarians received desperately needed reinforcements after the Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo from German Army soldiers rushed in after the Russian offensive ordered by Kerensky of July 1917 failed.

Chlorine-arsenic agent and diphosgene gas shells were fired as part of a huge artillery barrage, followed by infantry using infiltration tactics, bypassing enemy strong points and attacking on the Italian rear.

The Italians, pushed back to defensive lines near Venice on the Piave River, had suffered 600,000 casualties to this point in the war.

Because of these losses, the Italian Government called to arms the so-called 99 Boys (Ragazzi del '99); the new class of conscripts born in 1899 who were turning 18 in 1917.

Archduke Joseph August of Austria decided for a two-pronged offensive, where it would prove impossible for the two forces to communicate in the mountains.

The Second Battle of the Piave River began with a diversionary attack near the Tonale Pass named Lawine, which the Italians repulsed after two days of fighting.

The other prong, led by general Svetozar Boroević von Bojna initially experienced success until aircraft bombed their supply lines and Italian reinforcements arrived.

The following day the Istrian cities of Rovigno and Parenzo, the Dalmatian islands of Lissa, Lagosta and Lissa, and the cities of Zara and Fiume were occupied: the latter was not included in the territories originally promised secretly by the Allies to Italy in case of victory, but the Italians decided to intervene in reply to a local National Council, formed after the flight of the Hungarians, and which had announced the union to the Kingdom of Italy.

The rhetoric of mutilated victory was adopted by Mussolini and led to the rise of Italian fascism, becoming a key point in the propaganda of Fascist Italy.

Historians regard mutilated victory as a "political myth", used by fascists to fuel Italian imperialism and obscure the successes of liberal Italy in the aftermath of World War I.

(From Italian weekly La Domenica del Corriere , 24 September 1916).