J. J. Thomson

Sir Joseph John Thomson (18 December 1856 – 30 August 1940) was an English physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1906 for his discovery of the electron, the first subatomic particle to be found.

In 1897, Thomson showed that cathode rays were composed of previously unknown negatively charged particles (now called electrons), which he calculated must have bodies much smaller than atoms and a very large charge-to-mass ratio.

[1] Thomson is also credited with finding the first evidence for isotopes of a stable (non-radioactive) element in 1913, as part of his exploration into the composition of canal rays (positive ions).

[1] The appointment caused considerable surprise, given that candidates such as Osborne Reynolds or Richard Glazebrook were older and more experienced in laboratory work.

[17] He was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1906, "in recognition of the great merits of his theoretical and experimental investigations on the conduction of electricity by gases."

He died on 30 August 1940; his ashes rest in Westminster Abbey,[18] near the graves of Sir Isaac Newton and his former student Ernest Rutherford.

Six of Thomson's research assistants and junior colleagues (Charles Glover Barkla,[20] Niels Bohr,[21] Max Born,[22] William Henry Bragg, Owen Willans Richardson[23] and Charles Thomson Rees Wilson[24]) won Nobel Prizes in physics, and two (Francis William Aston[25] and Ernest Rutherford[26]) won Nobel prizes in chemistry.

[27] Thomson's prize-winning master's work, Treatise on the motion of vortex rings, shows his early interest in atomic structure.

[17] His third book, Elements of the mathematical theory of electricity and magnetism (1895)[28] was a readable introduction to a wide variety of subjects, and achieved considerable popularity as a textbook.

[17] A series of four lectures, given by Thomson on a visit to Princeton University in 1896, were subsequently published as Discharge of electricity through gases (1897).

He concluded that the rays were composed of very light, negatively charged particles which were a universal building block of atoms.

He called the particles "corpuscles", but later scientists preferred the name electron which had been suggested by George Johnstone Stoney in 1891, prior to Thomson's actual discovery.

[30] In April 1897, Thomson had only early indications that the cathode rays could be deflected electrically (previous investigators such as Heinrich Hertz had thought they could not be).

A month after Thomson's announcement of the corpuscle, he found that he could reliably deflect the rays by an electric field if he evacuated the discharge tube to a very low pressure.

By comparing the deflection of a beam of cathode rays by electric and magnetic fields he obtained more robust measurements of the mass-to-charge ratio that confirmed his previous estimates.

[33][34] Thomson made the discovery around the same time that Walter Kaufmann and Emil Wiechert discovered the correct mass to charge ratio of these cathode rays (electrons).

[35] The name "electron" was adopted for these particles by the scientific community, mainly due to the advocation by George Francis FitzGerald, Joseph Larmor, and Hendrik Lorentz.

[36]: 273 The term was originally coined by George Johnstone Stoney in 1891 as a tentative name for the basic unit of electrical charge (which had then yet to be discovered).

[40] In 1920, Rutherford and his fellows agreed to call the nucleus of the hydrogen ion "proton", establishing a distinct name for the smallest known positively-charged particle of matter (that can exist independently anyway).

[41] In 1912, as part of his exploration into the composition of the streams of positively charged particles then known as canal rays, Thomson and his research assistant F. W. Aston channelled a stream of neon ions through a magnetic and an electric field and measured its deflection by placing a photographic plate in its path.

[1][2] Earlier, physicists debated whether cathode rays were immaterial like light ("some process in the aether") or were "in fact wholly material, and ... mark the paths of particles of matter charged with negative electricity", quoting Thomson.

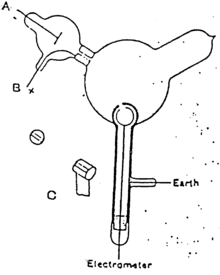

Cathode rays were produced in the side tube on the left of the apparatus and passed through the anode into the main bell jar, where they were deflected by a magnet.

[44] While supporters of the aetherial theory accepted the possibility that negatively charged particles are produced in Crookes tubes,[citation needed] they believed that they are a mere by-product and that the cathode rays themselves are immaterial.

Thomson constructed a Crookes tube with an electrometer set to one side, out of the direct path of the cathode rays.

Thomson could trace the path of the ray by observing the phosphorescent patch it created where it hit the surface of the tube.

[5] Previous experimenters had failed to observe this, but Thomson believed their experiments were flawed because their tubes contained too much gas.

Any electron beam would collide with some residual gas atoms within the Crookes tube, thereby ionizing them and producing electrons and ions in the tube (space charge); in previous experiments this space charge electrically screened the externally applied electric field.

He found that the mass-to-charge ratio was over a thousand times lower than that of a hydrogen ion (H+), suggesting either that the particles were very light and/or very highly charged.

Thomson himself remained critical of what his work established, in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech referring to "corpuscles" rather than "electrons".

This model was later proved incorrect when his student Ernest Rutherford showed that the positive charge is concentrated in the nucleus of the atom.