Jain philosophy

[1] It comprises all the philosophical investigations and systems of inquiry that developed among the early branches of Jainism in ancient India following the parinirvāṇa of Mahāvīra (c. 5th century BCE).

[1] One of the main features of Jain philosophy is its dualistic metaphysics, which holds that there are two distinct categories of existence: the living, conscious, or sentient beings (jīva) and the non-living or material entities (ajīva).

[1][2] Jain texts discuss numerous philosophical topics such as cosmology, epistemology, ethics, metaphysics, ontology, the philosophy of time, and soteriology.

[1] Jainism and its philosophical system are also notable for the belief in a beginning-less and cyclical universe, which posits a non-theistic understanding of the world and the complete rejection of a hypothetical creator deity.

[5] According to Paul Dundas, Jain philosophy has remained relatively stable throughout its long history and no major radical doctrinal shift has taken place.

[6] According to Ācārya Pujyapada's Sarvārthasiddhi, the ultimate good for a living being (jīva) is liberation from the cyclical world of reincarnation (saṃsāra).

[14] Jeffery D. Long also affirms the realistic nature of Jain metaphysics, which is a kind of pluralism that asserts the existence of various realities.

These are: nāma (name), sthāpanā (symbol), dravya (potentiality), bhāvatā (actuality), nirdeśa (definition), svāmitva (possession), sādhana (cause), adhikarana (location), sthiti (duration), vidhānatā (variety), sat (existence), samkhyā (numerical determination), ksetra (field occupied), sparśana (field touched), kāla (continuity ), antara (time-lapse), bhāva (states), andalpabahutva (relative size).

[27] Helmuth von Glasenapp pointed out that a central principle of Jain thought is its attempt to provide an ontology that includes both permanence and change.

It holds that correct knowledge is based on perception (pratyaksa), inference (anumana) and testimony (sabda or the word of scriptures).

[31][30] Some Jain texts add analogy (upamana) as the fourth reliable means, in a manner similar to epistemological theories found in other Indian religions.

[36] It refers to a kind of ontological pluralism and to the idea that reality is complex and multi-faceted and therefore can only be understood from a multiplicity of perspectives.

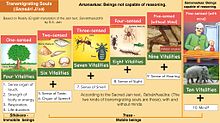

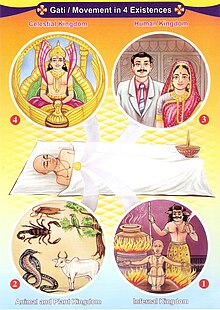

Thus, an embodied non-liberated soul is found in four realms of existence—heavens, hells, humans and animal world – in a continuous cycle of births and deaths also known as samsāra.

According to Jain thinkers, all living beings (even gods) experience extensive suffering and unquenchable desire (while worldly happiness is fleeting and small in comparison, like a mustard seed next to a mountain).

[70] According to the Jain philosophy, there are an infinite number of independent jīvas (sentients, living beings, souls) which fill the entire universe.

[94] During the each motion of the half-cycle of the wheel of time, 63 Śalākāpuruṣa or 63 illustrious persons, consisting of the 24 Tīrthaṅkaras and their contemporaries regularly appear.

[97] An atom also always possesses four qualities, a color (varna), a taste (rasa), a smell (gandha), and a certain kind of palpability (sparsha, touch) such as lightness, heaviness, softness, roughness, etc.

While the earliest texts focus on the role of the passions (kasāya, especially hatred) in attracting karmas, Umasvāti states that it is physical, verbal and mental activity which are responsible for the flowing in of karmic particles.

[117] Jain philosophers hold that harmful actions (hiṃsā) cause the soul to be tainted and defiled with karmas.

[119] As such, those who seek to stop (samvara) the influx of bad karmas (in order to reach liberation) should practice right conduct by observing certain ethical rules.

[120] Right conduct (samyak chāritra), is defined in the Sarvārthasiddhi as "the cessation of activity leading to the taking in of karmas by a wise person engaged in the removal of the causes of transmigration.

As explained by Dundas, the enlightened soul "will exist perpetually without any further rebirth in a disembodied and genderless state of perfect joy, energy, consciousness and knowledge.

[149][148] Harry Oldmeadow notes that Jain philosophy remained fairly standard throughout history and the later elaborations only sought to further elucidate preexisting doctrine and avoided changing the ontological status of the components.

The schism arose mainly on account of differences in question of practice of nudity amongst monks and whether women could achieve liberation in female bodies.

[153] According to Paul Dundas, Jain thinkers faced with the Muslim destruction of their temples also began to revisit their theory of "ahimsa" (non-violence).

Terapanth scholars like Tulasī (1913–1997) and Ācārya Mahāprajña (1920– 2010) have been influential intellectual figures in modern Jainism, writing numerous works on Jain philosophy.

Scholarly research has shown that philosophical concepts that are typically Indian – Karma, Ahimsa, Moksa, reincarnation and like – either have their origins in the sramana traditions (one of the most ancient of which is Jainism).

[162] Helmuth von Glasenapp also argues that the Jain idea of non-violence, and particularly its promotion of vegetarianism, had an influence on Hinduism, especially on Vaishnavism.

[163] Furthermore, von Glasenapp argues that some Hindu philosophical systems, particularly the dualistic Vedanta of Madhvacarya, was influenced by Jain philosophy.

[163] The Jain system of philosophy and ethics is also known for having had a major impact on modern figures like Dayanand Sarasvati and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.