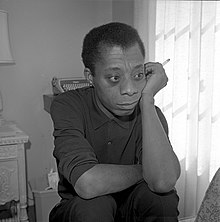

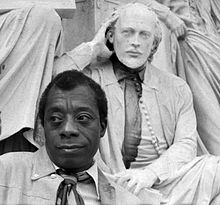

James Baldwin

James Arthur Baldwin (né Jones; August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) was an African-American writer and civil rights activist who garnered acclaim for his essays, novels, plays, and poems.

[72] During his Village years, Baldwin made a number of connections in New York's liberal literary establishment, primarily through Worth: Sol Levitas at The New Leader magazine, Randall Jarrell at The Nation, Elliot Cohen and Robert Warshow at Commentary, and Philip Rahv at Partisan Review.

He then published his first work of fiction, a short story called "Previous Condition", in the October 1948 issue of Commentary magazine, about a 20-something Black man who is evicted from his apartment—the apartment being a metaphor for white society.

[78] Disillusioned by the reigning prejudice against Black people in the United States, and wanting to gain external perspectives on himself and his writing, Baldwin settled in Paris, France, at the age of 24.

[80] In 1948, Baldwin received a $1,500 grant (equivalent to $19,022 in 2023)[81] from a Rosenwald Fellowship[82] in order to produce a book of photographs and essays that was to be both a catalog of churches and an exploration of religiosity in Harlem.

[85] Baldwin would later give various explanations for leaving America—sex, Calvinism, an intense sense of hostility which he feared would turn inward—but, above all, was the problem of race, which, throughout his life, had exposed him to a lengthy catalog of humiliations.

[91] In his early years in Saint-Germain, he met Otto Friedrich, Mason Hoffenberg, Asa Benveniste, Themistocles Hoetis, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Max Ernst, Truman Capote, and Stephen Spender, among many others.

In the latter work, Baldwin employs a character named Johnnie to trace his bouts of depression back to his inability to resolve the questions of filial intimacy raised by his relationship with his stepfather.

[105] Around the same time, Baldwin's circle of friends shifted away from primarily white bohemians toward a coterie of Black American expatriates: Baldwin grew close to dancer Bernard Hassell; spent significant amounts of time at Gordon Heath's club in Paris; regularly listened to Bobby Short and Inez Cavanaugh's performances at their respective haunts around the city; met Maya Angelou during her European tour of Porgy and Bess; and occasionally met with writers Richard Gibson and Chester Himes, composer Howard Swanson, and even Richard Wright.

[112] Baldwin went on to attend the Congress of Black Writers and Artists in September 1956, a conference which he found disappointing in its perverse reliance on European themes while nonetheless purporting to extol African originality.

[118] To settle the terms of his association with Knopf, Baldwin sailed back to the United States in April 1952 on the SS Île de France, where Themistocles Hoetis and Dizzy Gillespie were coincidentally also voyaging—his conversations with both on the ship were extensive.

"[122] Baldwin biographer David Leeming draws parallels between Go Tell It on the Mountain and James Joyce's 1916 A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: to "encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.

Writing from the expatriate's perspective, Part Three is the sector of Baldwin's corpus that most closely mirrors Henry James's methods: hewing out of one's distance and detachment from the homeland a coherent idea of what it means to be American.

In May 1954, the United States Supreme Court ordered schools to desegregate "with all deliberate speed"; in August 1955 the racist murder of Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi, and the subsequent acquittal of his killers were etched in Baldwin's mind until he wrote Blues for Mister Charlie; in December 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus; and in February 1956 Autherine Lucy was admitted to the University of Alabama before being expelled when whites rioted.

[148] Baldwin's lengthy essay "Down at the Cross" (frequently called The Fire Next Time after the title of the 1963 book in which it was published)[149] similarly showed the seething discontent of the 1960s in novel form.

The essay was originally published in two oversized issues of The New Yorker and landed Baldwin on the cover of Time magazine in 1963 while he was touring the South speaking about the restive Civil Rights Movement.

He concluded his career by publishing a volume of poetry, Jimmy's Blues (1983), as well as another book-length essay, The Evidence of Things Not Seen (1985), an extended reflection on race inspired by the Atlanta murders of 1979–1981.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture has an online exhibit titled "Chez Baldwin", which uses his historic French home as a lens to explore his life and legacy.

[181] Magdalena J. Zaborowska's 2018 book, Me and My House: James Baldwin's Last Decade in France, uses photographs of his home and his collections to discuss themes of politics, race, queerness, and domesticity.

In February 2016, Le Monde published an opinion piece by Thomas Chatterton Williams, a contemporary Black American expatriate writer in France, which spurred a group of activists to come together in Paris.

[184][185] Les Amis de la Maison Baldwin,[186] a French organization whose initial goal was to purchase the house by launching a capital campaign funded by the U.S. philanthropic sector, grew out of this effort.

Attempts to engage the French government in conservation of the property were dismissed by the mayor of Saint-Paul-de-Vence, Joseph Le Chapelain, whose statement to the local press claiming "nobody's ever heard of James Baldwin" mirrored that of Henri Chambon, the owner of the corporation that razed the house.

In all of Baldwin's works, but particularly in his novels, the main characters are twined up in a "cage of reality" that sees them fighting for their soul against the limitations of the human condition or against their place at the margins of a society consumed by various prejudices.

And it emphasizes the dire consequences, for individuals and racial groups, of the refusal to love.Baldwin returned to the United States in the summer of 1957, while the civil rights legislation of that year was being debated in Congress.

He had been powerfully moved by the image of a young girl, Dorothy Counts, braving a mob in an attempt to desegregate schools in Charlotte, North Carolina, and Partisan Review editor Philip Rahv had suggested he report on what was happening in the American South.

The delegation included Kenneth B. Clark, a psychologist who had played a key role in the Brown v. Board of Education decision; actor Harry Belafonte, singer Lena Horne, writer Lorraine Hansberry, and activists from civil rights organizations.

[204] When the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing happened in Birmingham three weeks after the March on Washington, Baldwin called for a nationwide campaign of civil disobedience in response to this "terrifying crisis".

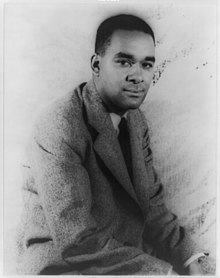

In Baldwin's 1949 essay "Everybody's Protest Novel", however, he indicated that Native Son, like Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), lacked credible characters and psychological complexity, and the friendship between the two authors ended.

Baldwin also knew Marlon Brando, Charlton Heston, Billy Dee Williams, Huey P. Newton, Nikki Giovanni, Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Genet (with whom he campaigned on behalf of the Black Panther Party), Lee Strasberg, Elia Kazan, Rip Torn, Alex Haley, Miles Davis, Amiri Baraka, Martin Luther King Jr., Dorothea Tanning, Leonor Fini, Margaret Mead, Josephine Baker, Allen Ginsberg, Chinua Achebe, and Maya Angelou.

On May 17, 2024, a blue plaque was unveiled by Nubian Jak Community Trust/Black History Walks to honour Baldwin at the site where in 1985 he visited the C. L. R. James Library in the London Borough of Hackney.