Jimmy Doolittle

[2][3] In 1927, he performed the first outside loop, thought at the time to be a fatal aerobatic maneuver, and two years later, in 1929, pioneered the use of "blind flying", where a pilot relies on flight instruments alone, which later won him the Harmon Trophy and made all-weather airline operations practical.

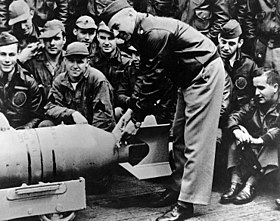

The raid used 16 B-25B Mitchell medium bombers with reduced armament to decrease weight and increase range, each with a crew of five and no escort fighter aircraft.

It was a major morale booster for the United States and Doolittle was celebrated as a hero, making him one of the most important national figures of the war.

The additional parts were dropped by air and installed, and Doolittle flew the plane to Del Rio, Texas, himself, taking off from a 400-yard (370 m) airstrip hacked out of the canyon floor.

Having at last returned to complete his college degree, he earned a Bachelor of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley in 1922, and joined the Lambda Chi Alpha fraternity.

In March 1924, he conducted aircraft acceleration tests at McCook Field, which became the basis of his master's thesis and led to his second Distinguished Flying Cross.

He was then assigned to McCook Field for experimental work, with additional duty as an instructor pilot to the 385th Bomb Squadron of the Air Corps Reserve.

Carried out in a Curtiss fighter at Wright Field in Ohio, Doolittle executed the dive from 10,000 feet (3,000 m), reached 280 miles per hour (450 km/h), bottomed out upside down, then climbed and completed the loop.

He was the first to recognize that true operational freedom in the air could not be achieved until pilots developed the ability to control and navigate aircraft in flight from takeoff run to landing rollout, regardless of the range of vision from the cockpit.

Arnold's approval to lead the top-secret attack of 16 B-25 medium bombers from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet, with targets in Tokyo, Kobe, Yokohama, Osaka and Nagoya.

Fifteen of the planes then headed for their recovery airfield in China, while one crew chose to land in Russia due to their bomber's unusually high fuel consumption.

Doolittle thought he would be court martialed due to having to launch the raid ahead of schedule after being spotted by a Japanese patrol boat and the loss of all the aircraft.

After the raid, the Japanese Imperial Army began the Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign (also known as Operation Sei-go) to prevent these eastern coastal provinces of China from being used again for an attack on Japan and to take revenge on the Chinese people.

Father Dunker wrote of the destruction of the town of Ihwang: "They shot any man, woman, child, cow, hog, or just about anything that moved, They raped any woman from the ages of 10–65, and before burning the town they thoroughly looted it ... None of the humans shot were buried either ..."[20] The Japanese entered Nancheng (Jiangxi), population 50,000 on June 11, "beginning a reign of terror so horrendous that missionaries would later dub it 'the Rape of Nancheng.'

Doolittle received the Medal of Honor from President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House for planning and leading his raid on Japan.

With the apparent certainty of being forced to land in enemy territory or to perish at sea, Lt. Col. Doolittle personally led a squadron of Army bombers, manned by volunteer crews, in a highly destructive raid on the Japanese mainland."

More significantly, Japanese commanders considered the raid deeply embarrassing, and their attempt to close the perceived gap in their Pacific defense perimeter led directly to the decisive American victory at the Battle of Midway in June 1942.

When asked from where the Tokyo raid was launched, President Roosevelt coyly said its base was Shangri-La, a fictional paradise from the popular novel and film Lost Horizon.

[24] In July 1942, as a brigadier general—he had been promoted by two grades on the day after the Tokyo attack, bypassing the rank of full colonel—Doolittle was assigned to the nascent Eighth Air Force.

In September, he commanded a raid against the Italian town of Battipaglia that was so thorough in its destruction that General Carl Andrew Spaatz sent him a joking message: "You're slipping Jimmy.

Doolittle continued to fly, despite the risk of capture, while being privy to the Ultra secret, which was that the German encryption systems had been broken by the British.

[33] Columnist Hanson Baldwin said that the Doolittle Board "caused severe damage to service effectiveness by recommendations intended to 'democratize' the Army—a concept that is self-contradictory".

[36]: 1443 Shortly after World War II, Doolittle spoke to an American Rocket Society conference at which a large number interested in rocketry attended.

Doolittle, Dr. Hugh Dryden and Stever selected committee members including Dr. Wernher von Braun from the Army Ballistic Missile Agency, Sam Hoffman of Rocketdyne, Abe Hyatt of the Office of Naval Research and Colonel Norman Appold from the USAF missile program, considering their potential contributions to US space programs and ability to educate NACA people in space science.

In 1952, following a string of three air crashes in two months at Elizabeth, New Jersey, the President of the United States, Harry S. Truman, appointed him to lead a presidential commission examining the safety of urban airports.

James H. "Jimmy" Doolittle died from a stroke at the age of 96 in Pebble Beach, California, on September 27, 1993, and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, near Washington, D.C., next to his wife.

Senator and retired Air Force Reserve Major General Barry Goldwater pinned on Doolittle's four-star insignia.

He is also one of only two persons (the other being Douglas MacArthur) to receive both the Medal of Honor and a British knighthood, when he was appointed an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath.

In 1972, Doolittle received the Tony Jannus Award for his distinguished contributions to commercial aviation, in recognition of the development of instrument flight.

With the apparent certainty of being forced to land in enemy territory or to perish at sea, Gen. Doolittle personally led a squadron of Army bombers, manned by volunteer crews, in a highly destructive raid on the Japanese mainland.