Marilyn Monroe

Her subsequent roles included a critically acclaimed performance in Bus Stop (1956) and her first independent production in The Prince and the Showgirl (1957), for which she received a nomination for BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Actress.

[6] Her mother, Gladys Pearl Baker (née Monroe), was born in Piedras Negras, Coahuila, Mexico[7] to a poor Midwestern family who migrated to California at the turn of the century.

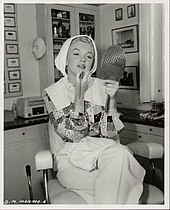

[92] To network, she frequented producers' offices, befriended gossip columnist Sidney Skolsky, and entertained influential male guests at studio functions, a practice she had begun at Fox.

[109] According to Spoto all three films featured her "essentially [as] a sexy ornament", but she received some praise from critics: Bosley Crowther of The New York Times described her as "superb" in As Young As You Feel and Ezra Goodman of the Los Angeles Daily News called her "one of the brightest up-and-coming [actresses]" for Love Nest.

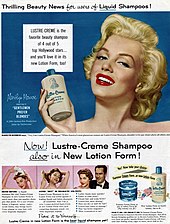

[110] Her popularity with audiences was also growing: she received several thousand fan letters a week, and was declared "Miss Cheesecake of 1951" by the army newspaper Stars and Stripes, reflecting the preferences of soldiers in the Korean War.

In the wake of the scandal, Monroe was featured on the cover of Life magazine as the "Talk of Hollywood", and gossip columnist Hedda Hopper declared her the "cheesecake queen" turned "box office smash".

She had begun taking acting classes with Michael Chekhov and mime Lotte Goslar soon after beginning the Fox contract,[119] and Clash by Night and Don't Bother to Knock showed her in different roles.

[121] She received positive reviews for her performance: The Hollywood Reporter stated that "she deserves starring status with her excellent interpretation", and Variety wrote that she "has an ease of delivery which makes her a cinch for popularity".

[154] Crowther of The New York Times and William Brogdon of Variety both commented favorably on Monroe, especially noting her performance of "Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend"; according to the latter, she demonstrated the "ability to sex a song as well as point up the eye values of a scene by her presence".

[160] Monroe was listed in the annual Top Ten Money Making Stars Poll in both 1953 and 1954,[142] and according to Fox historian Aubrey Solomon became the studio's "greatest asset" alongside CinemaScope.

[175][176] On January 29, 1954, fifteen days later,[177] they flew to Japan,[178] combining a "honeymoon" with his commitment to his former San Francisco Seals coach Lefty O'Doul,[179] to help train[180] Japanese baseball teams.

[192] In September 1954, Monroe began filming Billy Wilder's comedy The Seven Year Itch, starring opposite Tom Ewell as a woman who becomes the object of her married neighbor's sexual fantasies.

[216] In contrast, Monroe's relationship with Miller prompted some negative comments, such as Walter Winchell's statement that "America's best-known blonde moving picture star is now the darling of the left-wing intelligentsia.

[222] The filming took place in Idaho and Arizona, with Monroe "technically in charge" as the head of MMP, occasionally making decisions on cinematography and with Logan adapting to her chronic lateness and perfectionism.

[230] The Saturday Review of Literature wrote that Monroe's performance "effectively dispels once and for all the notion that she is merely a glamour personality" and Crowther proclaimed: "Hold on to your chairs, everybody, and get set for a rattling surprise.

[254] Monroe's performance earned her a Golden Globe for Best Actress in a Leading Role - Musical or Comedy,[255] and prompted Variety to call her "a comedienne with that combination of sex appeal and timing that just can't be beat".

[267][269] She later detailed her experience to psychiatrist Ralph Greenson:[267]There was no empathy at Payne-Whitney — it had a very bad effect — they asked me after putting me in a 'cell' (I mean cement blocks and all) for very disturbed depressed patients (except I felt I was in some kind of prison for a crime I hadn't committed).

[280] Its reviews were mixed,[280] with Variety complaining of frequently "choppy" character development,[281] and Bosley Crowther calling Monroe "completely blank and unfathomable" and writing that "unfortunately for the film's structure, everything turns upon her".

[314] French artist Jean Cocteau commented that her death "should serve as a terrible lesson to all those whose chief occupation consists of spying on and tormenting film stars", her former co-star Laurence Olivier deemed her "the complete victim of ballyhoo and sensation", and Bus Stop director Joshua Logan said that she was "one of the most unappreciated people in the world".

[342] Film scholar Thomas Harris wrote that her working-class roots and lack of family made her appear more sexually available, "the ideal playmate", in contrast to her contemporary, Grace Kelly, who was also marketed as an attractive blonde, but due to her upper-class background was seen as a sophisticated actress, unattainable for the majority of male viewers.

[352] Spoto likewise describes her as the embodiment of "the postwar ideal of the American girl, soft, transparently needy, worshipful of men, naïve, offering sex without demands", which is echoed in Molly Haskell's statement that "she was the Fifties fiction, the lie that a woman had no sexual needs, that she is there to cater to, or enhance, a man's needs.

"[353] Monroe's contemporary Norman Mailer wrote that "Marilyn suggested sex might be difficult and dangerous with others, but ice cream with her", while Groucho Marx characterized her as "Mae West, Theda Bara, and Bo Peep all rolled into one".

[355] Dyer has also argued that Monroe's blonde hair became her defining feature because it made her "racially unambiguous" and exclusively white just as the civil rights movement was beginning, and that she should be seen as emblematic of racism in twentieth-century popular culture.

[357] According to Banner, she sometimes challenged prevailing racial norms in her publicity photographs; for example, in an image featured in Look in 1951, she was shown in revealing clothes while practicing with African-American singing coach Phil Moore.

[359] Banner calls her the symbol of populuxe, a star whose joyful and glamorous public image "helped the nation cope with its paranoia in the 1950s about the Cold War, the atom bomb, and the totalitarian communist Soviet Union".

The Smithsonian Institution has included her on their list of "100 Most Significant Americans of All Time",[369] and both Variety and VH1 have placed her in the top ten in their rankings of the greatest popular culture icons of the twentieth century.

[381] She has been written about by scholars and journalists who are interested in gender and feminism;[382] these writers include Gloria Steinem, Jacqueline Rose,[383] Molly Haskell,[384] Sarah Churchwell,[376] and Lois Banner.

Owing to the contrast between her stardom and troubled private life, Monroe is closely linked to broader discussions about modern phenomena such as mass media, fame, and consumer culture.

[388] According to academic Susanne Hamscha, Monroe has continued relevance to ongoing discussions about modern society, and she is "never completely situated in one time or place" but has become "a surface on which narratives of American culture can be (re)constructed".

[393] Jonathan Rosenbaum stated that "she subtly subverted the sexist content of her material" and that "the difficulty some people have discerning Monroe's intelligence as an actress seems rooted in the ideology of a repressive era, when super feminine women weren't supposed to be smart".