Joseph Desha

By 1824, the Panic of 1819 had ruined Kentucky's economy, and Desha made a second campaign for the governorship almost exclusively on promises of relief for the state's large debtor class.

In a final act of defiance, Desha threatened to refuse to vacate the governor's mansion, although he ultimately acquiesced without incident, ceding the governorship to his successor, National Republican Thomas Metcalfe.

[3] In July 1781, Desha's family relocated to Fayette County, Kentucky, and the following year, they settled in what was then known as Cumberland district near the present-day city of Gallatin, Tennessee.

[18] He responded to Governor Isaac Shelby's call for volunteers to serve in William Henry Harrison's campaign into Upper Canada.

[20] Desha's charge was a contributing factor in Congress's decision to remove Harrison's name from a resolution of thanks for service in the Northwest Army and withhold from him a Congressional Gold Medal.

[25] The act, sponsored by fellow Kentuckian Richard Mentor Johnson, modified congressional compensation, paying each member a flat salary of $1,500 a year instead of a $6 per diem while Congress was in session.

[25] Every member of the Kentucky delegation that voted for the bill – excepting Johnson and Henry Clay, who were both extremely popular – lost his congressional seat, either because he did not seek reelection or because he was defeated by another candidate.

[5] On March 14, 1818, he voted with the minority against a resolution introduced by South Carolina's William Lowndes asserting Congress's power to appropriate federal funds for the construction of internal improvements.

[1] In the aftermath of the Panic of 1819 – the first major financial crisis in United States history – the primary issue of the campaign was debt relief.

[29] Opposed to them was the Anti-Relief Party or faction; it was composed primarily of the state's aristocracy, many of whom were creditors to the land speculators and demanded that their contracts be adhered to without interference from the government.

[34] Offering no specific platform, he focused exclusively on the idea that he opposed "judicial usurpation" and believed "all power belonged to the people".

[37] Desha attacked Tompkins' record as a judge, claiming that he had consistently supported the Second Bank of the United States and the current Court of Appeals.

[41] In contrast to his rhetoric in favor of a strong, well-equipped army and navy, opponents claimed he had actually voted against increasing the military's budget.

[41] As further evidence of his lack of trustworthiness, they pointed to his vote for William H. Crawford while serving as a presidential elector in 1816, even though Kentuckians were nearly unanimous in their support of James Monroe.

[41] Although Desha was universally acknowledged as the leading candidate during the early months of the campaign, as election day approached, some began to doubt whether he could withstand the withering attacks of the Anti-Relief Party.

[1] Desha and his allies in the General Assembly interpreted the victory as a mandate from the voters to aggressively pursue their debt relief agenda.

He advocated using excess money earmarked for education to construct hard-surfaced roads in the state, but the General Assembly was less responsive to this suggestion.

[50][57] Desha's message to the newly reconstituted General Assembly remained critical of banks and the judiciary, but urged legislators to seek a compromise to resolve the court question.

[42] Governor Desha appeared before the legislative committee considering the bill on November 26 and asked that they report it favorably to the full legislature.

[66] At his trial in December, Isaac Desha requested the change of venue; the case was transferred to Harrison County and scheduled for early January.

[71] Despite the best efforts of his father to secure a favorable venue, judge, and defense team, on January 31, 1825, the jury convicted Isaac Desha of murder and sentenced him to hang.

[76] Judge Brown overturned the verdict because the prosecution had not proven that the murder took place in Fleming County, as alleged in the indictment against Desha.

[74][75] The state argued that this was of no consequence, since a change of venue had already been granted, but the judge's ruling stood, and Governor Desha's reputation took a further hit.

[74] In July 1826, Isaac Desha, free on bail while awaiting a third trial and apparently in a highly intoxicated state, attempted suicide by cutting his own throat.

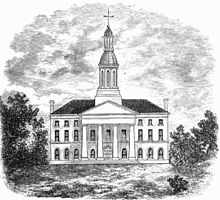

From the time Holley assumed the post of president in 1818, the university had risen to national prominence and attracted well-qualified and well-respected faculty members such as Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, Daniel Drake, Charles Caldwell, William T. Barry, and Jesse Bledsoe.

[82] Desha maintained that, because Holley had not silenced the student, he was at fault for tacitly condoning disrespectful criticism of the state's chief executive.

[82] He claimed that the university had not made wise use of the public funding allocated to it by previous Assemblies, noting in particular that Holley's salary as president exceeded his own.

[85] Kentucky historian James C. Klotter opined that, with Holley's departure, "perhaps the state's best chance for a world-class university had passed.

[4] Although Metcalfe was the son of a Revolutionary War soldier, his nickname of "Old Stone Hammer" indicated his pride in his trade of masonry, which was considered a common profession.

[88] Clark records as legend that, after drinking heavily at a local tavern, Metcalfe and some of his supporters formed a mob and went to the governor's mansion to evict him by force.