Joseph Smith

Smith and his followers left Ohio and Missouri after the collapse of the church-sponsored Kirtland Safety Society and violent skirmishes with non-Mormon Missourians escalated into the Mormon extermination order.

Joseph Smith launched a presidential campaign in 1844 on a platform which proposed gradually ending slavery, protecting the liberties of Latter Day Saints and other minorities, reducing the size of Congress, reestablishing a national bank, reforming prisons, and annexing Texas, California, and Oregon.

Fearing an invasion of Nauvoo, Smith rode to Carthage, Illinois, to stand trial, but was shot and killed by a mob that stormed the jailhouse.

His followers accepted his teachings as prophetic and revelatory, and several of these texts were canonized by denominations of the Latter Day Saint movement, which continue to treat them as scripture.

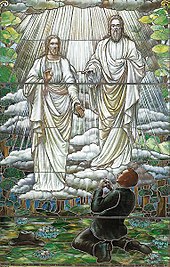

[18] He said that in 1820, while he had been praying in a wooded area near his home, God the Father and Jesus Christ together appeared to him, told him his sins were forgiven, and said that all contemporary churches had "turned aside from the gospel".

[28] Family members supplemented their meager farm income by hiring out for odd jobs and working as treasure seekers,[29] a type of magical supernaturalism common during the period.

[55] The completed work, titled the Book of Mormon, was published in Palmyra by printer Egbert Bratt Grandin[56] and was first advertised for sale on March 26, 1830.

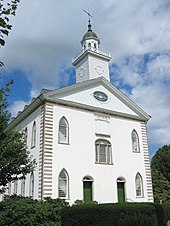

[57] Less than two weeks later, on April 6, 1830, Smith and his followers formally organized the Church of Christ, and small branches were established in Manchester, Fayette, and Colesville, New York.

[62] In response, Smith dictated a revelation which clarified his office as a prophet and an apostle, stating that only he had the ability to declare doctrine and scripture for the church.

[65] On their way to Missouri, Cowdery's party passed through northeastern Ohio, where Sidney Rigdon and over a hundred followers of his variety of Campbellite Restorationism converted to the Church of Christ, swelling the ranks of the new organization dramatically.

[67] With growing opposition in New York, Smith announced a revelation that his followers should gather to Kirtland, Ohio, establish themselves as a people and await word from Cowdery's mission.

[99] Political and religious differences between old Missourians and newly arriving Latter Day Saint settlers provoked tensions between the two groups, much as they had in Jackson County.

[112] Illinois then accepted Mormon refugees who gathered along the banks of the Mississippi River,[113] where Smith purchased high-priced, swampy woodland in the hamlet of Commerce.

[115] During the summer of 1839, while Mormons in Illinois suffered from a malaria epidemic, Smith sent Young and other apostles to missions in Europe, where they made numerous converts, many of them poor factory workers.

After an unknown assailant shot and wounded Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs in May 1842, anti-Mormons circulated rumors that Smith's bodyguard, Porter Rockwell, was the gunman.

After receiving noncommittal or negative responses, he announced his own independent candidacy for president of the United States, suspended regular proselytizing, and sent out the Quorum of the Twelve and hundreds of other political missionaries.

[153] Destruction of the newspaper provoked a strident call to arms from Thomas C. Sharp, editor of the Warsaw Signal and longtime critic of Smith.

[175] Meanwhile, Smith's reputation is ambivalent in the Community of Christ, which continues "honoring his role" in the church's founding history but deemphasizes his human leadership.

[185] Smaller groups followed Rigdon and James J. Strang, who had based his claim on a letter of appointment ostensibly written by Smith but which some scholars believe was forged.

Instead of presenting his ideas with logical arguments, Smith dictated authoritative scripture-like "revelations" and let people decide whether to believe,[214] doing so with what Peter Coviello calls "beguiling offhandedness".

[225] Biographer Robert V. Remini calls the Book of Mormon "a typically American story" that "radiates the revivalist passion of the Second Great Awakening".

[228] According to historian Daniel Walker Howe, the book's "dominant themes are biblical, prophetic, and patriarchal, not democratic or optimistic" like the prevailing American culture.

[235] In June 1830, Smith dictated a revelation in which Moses narrates a vision in which he sees "worlds without number" and speaks with God about the purpose of creation and the relation of humankind to deity.

[255] An 1832 revelation called "The Vision" added to the fundamentals of sin and atonement, and introduced doctrines of life after salvation, exaltation, and a heaven with degrees of glory.

[257] In 1833, at a time of temperance agitation, Smith delivered a revelation called the "Word of Wisdom", which counseled a diet of wholesome herbs, fruits, grains and a sparing use of meat.

[258] The Word of Wisdom was originally framed as a recommendation rather than a commandment and was not strictly followed by Smith and other early Latter Day Saints,[259] though it later became a requirement in the LDS Church.

[262] For instance, the doctrines of baptism for the dead and the nature of God were introduced in sermons, and one of Smith's most famed statements, about there being "no such thing as immaterial matter", was recorded from a casual conversation with a Methodist preacher.

[270] Smith extended this materialist conception to all existence and taught that "all spirit is matter", meaning that a person's embodiment in flesh was not a sign of fallen carnality, but a divine quality that humans shared with deity.

For instance, in the early 1830s, Smith temporarily instituted a form of religious communism, called the United Order, that required Latter Day Saints to give all their property to the church, to be divided among the faithful.

[301] In Smith's theology, marrying in polygamy made it possible for practitioners to unlearn the Christian tradition which identified the physical body as carnal, and to instead recognize their embodied joy as sacred.