Joule–Thomson effect

In thermodynamics, the Joule–Thomson effect (also known as the Joule–Kelvin effect or Kelvin–Joule effect) describes the temperature change of a real gas or liquid (as differentiated from an ideal gas) when it is expanding; typically caused by the pressure loss from flow through a valve or porous plug while keeping it insulated so that no heat is exchanged with the environment.

[7][8] In hydraulics, the warming effect from Joule–Thomson throttling can be used to find internally leaking valves as these will produce heat which can be detected by thermocouple or thermal-imaging camera.

The throttling due to the flow resistance in supply lines, heat exchangers, regenerators, and other components of (thermal) machines is a source of losses that limits their performance.

Since it is a constant-enthalpy process, it can be used to experimentally measure the lines of constant enthalpy (isenthalps) on the

[9] The effect is named after James Prescott Joule and William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, who discovered it in 1852.

It followed upon earlier work by Joule on Joule expansion, in which a gas undergoes free expansion in a vacuum and the temperature is unchanged, if the gas is ideal.

The adiabatic (no heat exchanged) expansion of a gas may be carried out in a number of ways.

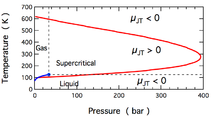

This coefficient may be either positive (corresponding to cooling) or negative (heating); the regions where each occurs for molecular nitrogen, N2, are shown in the figure.

Note that most conditions in the figure correspond to N2 being a supercritical fluid, where it has some properties of a gas and some of a liquid, but can not be really described as being either.

At temperatures below the gas-liquid coexistence curve, N2 condenses to form a liquid and the coefficient again becomes negative.

There are two factors that can change the temperature of a fluid during an adiabatic expansion: a change in internal energy or the conversion between potential and kinetic internal energy.

[12] Thus, even if the internal energy does not change, the temperature can change due to conversion between kinetic and potential energy; this is what happens in a free expansion and typically produces a decrease in temperature as the fluid expands.

[13][14] If work is done on or by the fluid as it expands, then the total internal energy changes.

to that expected for an ideal gas at the same temperature is called the compressibility factor,

The physical mechanism associated with the Joule–Thomson effect is closely related to that of a shock wave,[17] although a shock wave differs in that the change in bulk kinetic energy of the gas flow is not negligible.

With that in mind, the following table explains when the Joule–Thomson effect cools or warms a real gas: Helium and hydrogen are two gases whose Joule–Thomson inversion temperatures at a pressure of one atmosphere are very low (e.g., about 40 K, −233 °C for helium).

Thus, helium and hydrogen warm when expanded at constant enthalpy at typical room temperatures.

is always equal to zero: ideal gases neither warm nor cool upon being expanded at constant enthalpy.

The critical point falls inside the region where the gas cools on expansion.

The cooling produced in the Joule–Thomson expansion makes it a valuable tool in refrigeration.

[8][20] The effect is applied in the Linde technique as a standard process in the petrochemical industry, where the cooling effect is used to liquefy gases, and in many cryogenic applications (e.g. for the production of liquid oxygen, nitrogen, and argon).

[21] To prove this, the first step is to compute the net work done when a mass m of the gas moves through the plug.

This means that where u1 and u2 denote the specific internal energies of the gas in regions 1 and 2, respectively.

This means that the mass fraction of the liquid in the liquid–gas mixture leaving the throttling valve is 40%.

do not use the original method used by Joule and Thomson, but instead measure a different, closely related quantity.

The first step in obtaining these results is to note that the Joule–Thomson coefficient involves the three variables T, P, and H. A useful result is immediately obtained by applying the cyclic rule; in terms of these three variables that rule may be written Each of the three partial derivatives in this expression has a specific meaning.

It is used in the following to obtain a mathematical expression for the Joule–Thomson coefficient in terms of the volumetric properties of a fluid.

To proceed further, the starting point is the fundamental equation of thermodynamics in terms of enthalpy; this is Now "dividing through" by dP, while holding temperature constant, yields The partial derivative on the left is the isothermal Joule–Thomson coefficient,

, and the one on the right can be expressed in terms of the coefficient of thermal expansion via a Maxwell relation.

is zero, occurs when the coefficient of thermal expansion is equal to the inverse of the temperature.