Julius Caesar (play)

Caesar's right-hand man Antony stirs up hostility against the conspirators and Rome becomes embroiled in a dramatic civil war.

During the feast of Lupercal, Caesar holds a victory parade and a soothsayer warns him to "Beware the ides of March," which he ignores.

Casca tells them that each time Caesar refused it with increasing reluctance, hoping that the crowd watching would insist that he accept the crown.

On the eve of the ides of March, the conspirators meet and reveal that they have forged letters of support from the Roman people to tempt Brutus into joining.

Brutus reads the letters and, after much moral debate, decides to join the conspiracy, thinking that Caesar should be killed to prevent him from doing anything against the people of Rome if he were ever to be crowned.

However, Antony makes a subtle and eloquent speech over Caesar's corpse, beginning "Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears!

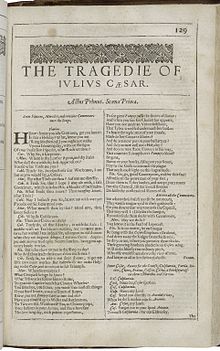

Julius Caesar was originally published in the First Folio of 1623, but a performance was mentioned by Thomas Platter the Younger in his diary in September 1599.

Based on these two points, as well as several contemporary allusions, and the belief that the play is similar to Hamlet in vocabulary, and to Henry V and As You Like It in metre,[12] scholars have suggested 1599 as a probable date.

The Folio text is notable for its quality and consistency; scholars judge it to have been set into type from a theatrical prompt-book.

At the time of its creation and first performance, Queen Elizabeth, a strong ruler, was elderly and had refused to name a successor, leading to worries that a civil war similar to that of Rome might break out after her death.

He points out that Casca praises Brutus at face value, but then inadvertently compares him to a disreputable joke of a man by calling him an alchemist, "Oh, he sits high in all the people's hearts,/And that which would appear offense in us/ His countenance, like richest alchemy,/ Will change to virtue and worthiness" (I.iii.158–160).

[17] Joseph W. Houppert acknowledges that some critics have tried to cast Caesar as the protagonist, but that ultimately Brutus is the driving force in the play and is, therefore, the tragic hero.

[21] Thomas Platter the Younger, a Swiss traveler, saw a tragedy about Julius Caesar at a Bankside theatre on 21 September 1599, and this was most likely Shakespeare's play, as there is no obvious alternative candidate.

In 1851, the German composer Robert Schumann wrote a concert overture Julius Caesar, inspired by Shakespeare's play.

[32] The Canadian comedy duo Wayne and Shuster parodied Julius Caesar in their 1958 sketch Rinse the Blood off My Toga.

In the Ray Bradbury book Fahrenheit 451, some of the character Beatty's last words are "There is no terror, Cassius, in your threats, for I am armed so strong in honesty that they pass me as an idle wind, which I respect not!"

The play's line "the fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves", spoken by Cassius in Act I, scene 2, is often referenced in popular culture.

Barrie play Dear Brutus, and also gave its name to the best-selling young adult novel The Fault in Our Stars by John Green and its film adaptation.

The same line was quoted in Edward R. Murrow's epilogue of his famous 1954 See It Now documentary broadcast concerning Senator Joseph R. McCarthy.

The line "And therefore think him as a serpent's egg / Which hatched, would, as his kind grow mischievous; And kill him in the shell" spoken by Brutus in Act II, Scene 1, is referenced in the Dead Kennedys song "California über alles".

The play was previously discussed in a conversation between Julian Bashir and Elim Garak in the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode "Improbable Cause".

Julius Caesar has been adapted to a number of film productions, including: Modern adaptions of the play have often made contemporary political references,[46] with Caesar depicted as resembling a variety of political leaders, including Huey Long, Margaret Thatcher, and Tony Blair,[47] as well as Fidel Castro and Oliver North.

[48][49] Scholar A. J. Hartley stated that this is a fairly "common trope" of Julius Caesar performances: "Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, the rule has been to create a recognizable political world within the production.

[46] In 2017, however, a modern adaptation of the play at New York's Shakespeare in the Park (performed by The Public Theater) depicted Caesar with the likeness of then-president Donald Trump and thereby aroused ferocious controversy, drawing criticism by media outlets such as The Daily Caller and Breitbart and prompting corporate sponsors Bank of America and Delta Air Lines to pull their financial support.

[46][50][51][52] The Public Theater stated that the message of the play is not pro-assassination and that the point is that "those who attempt to defend democracy by undemocratic means pay a terrible price and destroy the very thing they are fighting to save."

[54][55][56][57] The protests were praised by American Family Association director Sandy Rios who compared the play with the execution of Christians by damnatio ad bestias.

The commoners in the first scene sing modern punk music and Caesar distributes red hats to the audience that are remarkably similar to Donald Trump's campaign merchandise.