Kansas–Nebraska Act

It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by President Franklin Pierce.

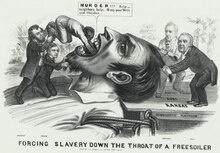

However, the Kansas–Nebraska Act effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, stoking national tensions over slavery and contributing to a series of armed conflicts known as "Bleeding Kansas".

To win the support of Southerners like Atchison, Pierce and Douglas agreed to back the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, with the status of slavery instead decided based on "popular sovereignty".

[2] Douglas and Pierce hoped that popular sovereignty would help bring an end to the national debate over slavery, but the Kansas–Nebraska Act outraged Northerners.

In 1845, Stephen A. Douglas, then serving in his first term in the U.S. House of Representatives, had submitted an unsuccessful plan to organize the Nebraska Territory formally, as the first step in building a railroad with its eastern terminus in Chicago.

Railroad proposals were debated in all subsequent sessions of Congress with cities such as Chicago, St. Louis, Quincy, Memphis, and New Orleans competing to be the jumping-off point for the construction.

When Congress reconvened on December 5, 1853, the group, termed the F Street Mess, along with Virginian William O. Goode, formed the nucleus that would insist on slaveholder equality in Nebraska.

[7] Douglas was also a fervent believer in popular sovereignty—the policy of letting the voters, almost exclusively white males, of a territory decide whether or not slavery should exist in it.

[8] Iowa Senator Augustus C. Dodge immediately reintroduced the same legislation to organize Nebraska that had stalled in the previous session; it was referred to Douglas's committee on December 14.

"[13] In a report accompanying the bill, Douglas's committee wrote that the Utah and New Mexico Acts: ... were intended to have a far more comprehensive and enduring effect than the mere adjustment of the difficulties arising out of the recent acquisition of Mexican territory.

They were designed to establish certain great principles, which would not only furnish adequate remedies for existing evils, but, in all times to come, avoid the perils of a similar agitation, by withdrawing the question of slavery from the halls of Congress and the political arena, and committing it to the arbitrament of those who were immediately interested in, and alone responsible for its consequences.

On January 16 Dixon surprised Douglas by introducing an amendment that would repeal the section of the Missouri Compromise that prohibited slavery north of the 36°30' parallel.

[17] Pierce was not enthusiastic about the implications of repealing the Missouri Compromise and had barely referred to Nebraska in his State of the Union message delivered December 5, 1853, just a month before.

Close advisors Senator Lewis Cass of Michigan, a proponent of popular sovereignty as far back as 1848 as an alternative to the Wilmot Proviso, and Secretary of State William L. Marcy both told Pierce that repeal would create serious political problems.

[21] On January 23, a revised bill was introduced in the Senate that repealed the Missouri Compromise and split the unorganized land into two new territories: Kansas and Nebraska.

The publications and speeches of abolitionists, some of them former slaves themselves, were telling Northerners that the supposed beneficence of slavery was a Southern lie, and that enslaving another person was un-Christian, a horrible sin that must be fought.

The Democrats held large majorities in each house, and Douglas, "a ferocious fighter, the fiercest, most ruthless, and most unscrupulous that Congress had perhaps ever known", led a tightly disciplined party.

The day after the bill was reintroduced, two Ohioans, Representative Joshua Giddings and Senator Salmon P. Chase, published a free-soil response, "Appeal of the Independent Democrats in Congress to the People of the United States": We arraign this bill as a gross violation of a sacred pledge; as a criminal betrayal of precious rights; as part and parcel of an atrocious plot to exclude from vast unoccupied region immigrants from the Old World and free laborers from our States, and convert it into a dreary region of despotism, inhabited by masters and slaves.

He expressed his sense of betrayal, recalling that Chase, "with a smiling face and the appearance of friendship", had appealed for a postponement of debate on the ground that he had not yet familiarized himself with the bill.

"Little did I suppose at the time that I granted that act of courtesy", Douglas remarked, that Chase and his compatriots had published a document "in which they arraigned me as having been guilty of a criminal betrayal of my trust", of bad faith, and of plotting against the cause of free government.

Douglas remained the main advocate for the bill while Chase, William Seward, of New York, and Charles Sumner, of Massachusetts, led the opposition.

Realizing from the vote to stall that the act faced an uphill struggle, the Pierce administration made it clear to all Democrats that passage of the bill was essential to the party and would dictate how federal patronage would be handled.

On April 25, in a House speech that biographer William Nisbet Chambers called "long, passionate, historical, [and] polemical", Benton attacked the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, which he "had stood upon ... above thirty years, and intended to stand upon it to the end—solitary and alone, if need be; but preferring company".

[34] Historian Michael Morrison wrote: A filibuster led by Lewis D. Campbell, an Ohio free-soiler, nearly provoked the House into a war of more than words.

White American settlers from both the free-soil North and pro-slavery South flooded the Northern Indian Territory, hoping to influence the vote on slavery that would come following the admittance of Kansas and, to a lesser extent, Nebraska to the United States.

In 1854 alone, the U.S. agreed to acquire lands in Kansas or Nebraska from several tribes including the Kickapoo,[60] Delaware,[61] Omaha,[62] Shawnee,[63] Otoe and Missouri,[64] Miami,[65] and Kaskaskia and Peoria.

While noting intemperance, or alcoholism, as a leading cause of death, Cumming specifically cited cholera, smallpox, and measles, none of which the Native Americans were able to treat.

[70] The disastrous epidemics exemplified the Osage people, who lost an estimated 1300 lives to scurvy, measles, smallpox, and scrofula between 1852 and 1856,[71] contributing, in part, to the massive decline in population, from 8000 in 1850 to just 3500 in 1860.

[86] Two days after Buchanan's inauguration, Chief Justice Roger Taney delivered the Dred Scott decision, which asserted that Congress had no constitutional power to exclude slavery in the territories.

[87] Douglas continued to support the doctrine of popular sovereignty, but Buchanan insisted that Democrats respect the Dred Scott decision and its repudiation of federal interference with slavery in the territories.