Khmer Rouge

Following their victory, the Khmer Rouge–who were led by Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary, Son Sen, and Khieu Samphan–immediately set about forcibly evacuating the country's major cities.

[30]: 26 Its leaders and theorists, most of whom had been exposed to the heavily Stalinist outlook of the French Communist Party during the 1950s,[39]: 249 developed a distinctive and eclectic "post-Leninist" ideology that drew on elements of Stalinism, Maoism and the postcolonial theory of Frantz Fanon.

[48]: 284 The policy of evacuating major towns, as well as providing a reserve of easily exploitable agricultural labour, was likely viewed positively by the Khmer Rouge's peasant supporters as removing the source of their debts.

[48]: 191 While in practice religious activity was not tolerated, the relationship of the CPK to the majority Cambodian Theravada Buddhism was complex; several key figures in its history, such as Tou Samouth and Ta Mok, were former monks, along with many lower level cadres, who often proved some of the strictest disciplinarians.

[48]: 191 While there was extreme harassment of Buddhist institutions, there was a tendency for the CPK regime to internalise and reconfigure the symbolism and language of Cambodian Buddhism so that many revolutionary slogans mimicked the formulae learned by young monks during their training.

[48]: 347 While François Ponchaud stated that Christians were invariably taken away and killed with the accusation of having links with the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, at least some cadres appear to have regarded it as preferable to the "feudal" class-based Buddhism.

According to the historian David P. Chandler, the leftist Issarak groups aided by the Viet Minh occupied a sixth of Cambodia's territory by 1952, and on the eve of the Geneva Conference in 1954, they controlled as much as one half of the country.

According to Democratic Kampuchea's perspective of party history, the Viet Minh's failure to negotiate a political role for the KPRP at the 1954 Geneva Conference represented a betrayal of the Cambodian movement, which still controlled large areas of the countryside, and which commanded at least 5,000 armed men.

Sihanouk habitually labelled local leftists the Khmer Rouge, a term that later came to signify the party and the state headed by Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, Khieu Samphan and their associates.

Described by one source as a "determined, rather plodding organizer", Pol Pot failed to obtain a degree, but according to Jesuit priest Father François Ponchaud he acquired a taste for the classics of French literature as well as an interest in the writings of Karl Marx.

Meeting with Khmers who were fighting with the Viet Minh (but subsequently judged them to be too subservient to the Vietnamese), they became convinced that only a tightly disciplined party organization and a readiness for armed struggle could achieve revolution.

After the end of the war, he moved to Phnom Penh under Tou Samouth's "urban committee", where he became an important point of contact between above-ground parties of the left and the underground secret communist movement.

His ally Nuon Chea, also known as Long Reth, became deputy general secretary, but Pol Pot and Ieng Sary were named to the Political Bureau to occupy the third and the fifth highest positions in the renamed party's hierarchy.

[65] The region where Pol Pot and the others moved to was inhabited by tribal minorities, the Khmer Loeu, whose rough treatment (including resettlement and forced assimilation) at the hands of the central government made them willing recruits for a guerrilla struggle.

[74] Sihanouk's popular support in rural Cambodia allowed the Khmer Rouge to extend its power and influence to the point that by 1973 it exercised de facto control over the majority of Cambodian territory, although only a minority of its population.

Some scholars, including Michael Ignatieff, Adam Jones[77] and Greg Grandin,[78] have cited the United States intervention and bombing campaign (spanning 1965–1973) as a significant factor which led to increased support for the Khmer Rouge among the Cambodian peasantry.

"[30]: 16–19 Pol Pot biographer David P. Chandler writes that the bombing "had the effect the Americans wanted – it broke the Communist encirclement of Phnom Penh", but it also accelerated the collapse of rural society and increased social polarization.

[87] In 2009, China defended its past ties with previous Cambodian governments, including that of Democratic Kampuchea or Khmer Rouge, which at the time had a legal seat at the United Nations and foreign relations with more than 70 countries.

[48]: 158 A possible military coup attempt was made in May 1976, and its leader was a senior Eastern Zone cadre named Chan Chakrey, who had been appointed deputy secretary of the army's General Staff.

The exception was the Eastern Zone, which until 1976 was run by cadres who were closely connected with Vietnam rather than the Party Centre, where a more organised system seems to have existed under which children were given extra rations, taught by teachers who were drawn from the "base people" and given a limited number of official textbooks.

People were told to "forge" (លត់ដំ; lot dam) a new revolutionary character, that they were the "instruments" (ឧបករណ៍; opokar) of the ruling body known as Angkar (អង្គការ, The Organisation) and that nostalgia for pre-revolutionary times (ឈឺសតិអារម្មណ៍; chheu satek arom, or "memory sickness") could result in execution.

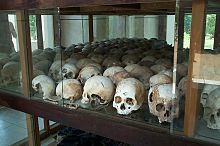

[106] Although considerably higher than earlier and more widely accepted estimates of Khmer Rouge executions, Etcheson argues that these numbers are plausible, given the nature of the mass grave and DC-Cam's methods, which are more likely to produce an under-count of bodies rather than an over-estimate.

In an interview conducted in 2018, historian David P. Chandler states that crimes against humanity was the term that best fit the atrocities of the regime and that some attempts to characterise the majority of the killings as genocide was flawed and at times politicised.

[35]: 268–9 In late 1976, with the Kampuchean economy underperforming, Pol Pot ordered a purge of the ministry of commerce, and Khoy Thoun and his subordinates who he had brought from the northern zone were arrested and tortured before being executed at Tuol Sleng.

On 25 December 1978, the Vietnamese armed forces along with the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation, an organization founded by Heng Samrin that included many dissatisfied former Khmer Rouge members,[48] invaded Cambodia and captured Phnom Penh on 7 January 1979.

[111] Despite its deposal, the Khmer Rouge retained its United Nations seat, which was occupied by Thiounn Prasith, an old companion of Pol Pot and Ieng Sary from their student days in Paris and one of the 21 attendees at the 1960 KPRP Second Congress.

[117] While Vietnam proposed to withdraw from Cambodia in return for a political settlement that would exclude the Khmer Rouge from power, the rebel coalition government as well as ASEAN, China and the United States, insisted that such a condition was unacceptable.

It began fighting the Cambodian coalition government which included the former Vietnamese-backed communists (headed by Hun Sen) as well as the Khmer Rouge's former non-communist and monarchist allies (notably Prince Rannaridh).

[125] After claiming to feel great remorse for his part in Khmer Rouge atrocities, Duch, head of Tuol Sleng where 16,000 men, women and children were sent to their deaths, surprised the court in his trial on 27 November 2009 with a plea for his freedom.

ICfC launched the Justice and History Outreach project in 2007 and has worked in villages in rural Cambodia with the goal of creating mutual understanding and empathy between victims and former members of the Khmer Rouge.