Christopher Marlowe

There have been many conjectures as to the nature and reason for his death, including a vicious bar-room fight, blasphemous libel against the church, homosexual intrigue, betrayal by another playwright, and espionage from the highest level: the Privy Council of Elizabeth I.

In 1587, the university hesitated to award his Master of Arts degree because of a rumour that he intended to go to the English seminary at Rheims in northern France, presumably to prepare for ordination as a Roman Catholic priest.

[8] If true, such an action on his part would have been a direct violation of royal edict issued by Queen Elizabeth I in 1585 criminalising any attempt by an English citizen to be ordained in the Roman Catholic Church.

[16] Despite the dire implications for Marlowe, his degree was awarded on schedule when the Privy Council intervened on his behalf, commending him for his "faithful dealing" and "good service" to the Queen.

There is no mention of espionage in the minutes, but its summation of the lost Privy Council letter is vague in meaning, stating that "it was not Her Majesties pleasure" that persons employed as Marlowe had been "in matters touching the benefit of his country should be defamed by those who are ignorant in th'affaires he went about."

Scholars agree the vague wording was typically used to protect government agents, but they continue to debate what the "matters touching the benefit of his country" actually were in Marlowe's case and how they affected the 23-year-old writer as he began his literary career in 1587.

[20][21][22] Much has been written on his brief adult life, including speculation of: his involvement in royally sanctioned espionage; his vocal declaration of atheism; his (possibly same-sex) sexual interests; and the puzzling circumstances surrounding his death.

[23][24] In 1587, when the Privy Council ordered the University of Cambridge to award Marlowe his degree as Master of Arts, it denied rumours that he intended to go to the English Catholic college in Rheims, saying instead that he had been engaged in unspecified "affaires" on "matters touching the benefit of his country".

Surviving college buttery accounts, which record student purchases for personal provisions, show that Marlowe began spending lavishly on food and drink during the periods he was in attendance; the amount was more than he could have afforded on his known scholarship income.

[31][32][33][34] Frederick S. Boas dismisses the possibility of this identification, based on surviving legal records which document Marlowe's "residence in London between September and December 1589".

Marlowe had been party to a fatal quarrel involving his neighbours and the poet Thomas Watson in Norton Folgate and was held in Newgate Prison for a fortnight.

[35] In fact, the quarrel and his arrest occurred on 18 September, he was released on bail on 1 October and he had to attend court, where he was acquitted on 3 December, but there is no record of where he was for the intervening two months.

[36] In 1592 Marlowe was arrested in the English garrison town of Flushing (Vlissingen) in the Netherlands, for alleged involvement in the counterfeiting of coins, presumably related to the activities of seditious Catholics.

The governor of Flushing had reported that each of the men had "of malice" accused the other of instigating the counterfeiting and of intending to go over to the Catholic "enemy"; such an action was considered atheistic by the Church of England.

Following Marlowe's arrest in 1593, Baines submitted to the authorities a "note containing the opinion of one Christopher Marly concerning his damnable judgment of religion, and scorn of God's word".

[22] Other scholars point to the frequency with which Marlowe explores homosexual themes in his writing: in Hero and Leander, Marlowe writes of the male youth Leander: "in his looks were all that men desire..."[49][50] Edward the Second contains the following passage enumerating homosexual relationships: The mightiest kings have had their minions; Great Alexander loved Hephaestion, The conquering Hercules for Hylas wept; And for Patroclus, stern Achilles drooped.

[52] The decision to start the play Dido, Queen of Carthage with a homoerotic scene between Jupiter and Ganymede that bears no connection to the subsequent plot has long puzzled scholars.

[55][44] In a second letter, Kyd said they had both been working for an aristocratic patron (probably Ferdinando Stanley), and he described Marlowe as blasphemous, disorderly, holding treasonous opinions, being an irreligious reprobate and "intemperate & of a cruel hart".

[57] Marlowe duly presented himself on 20 May 1593 but there apparently being no Privy Council meeting on that day, was instructed to "give his daily attendance on their Lordships, until he shall be licensed to the contrary".

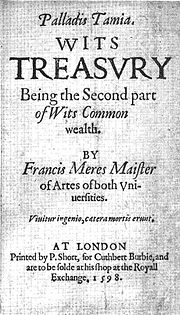

In his Palladis Tamia, published in 1598, Francis Meres says Marlowe was "stabbed to death by a bawdy serving-man, a rival of his in his lewd love" as punishment for his "epicurism and atheism".

[6] Marlowe had spent all day in a house in Deptford, owned by the widow Eleanor Bull, with three men: Ingram Frizer, Nicholas Skeres and Robert Poley.

Hotson had considered the possibility that the witnesses had "concocted a lying account of Marlowe's behaviour, to which they swore at the inquest, and with which they deceived the jury", but decided against that scenario.

[69] As an agent provocateur for the late Sir Francis Walsingham, Robert Poley was a consummate liar, the "very genius of the Elizabethan underworld", and was on record as saying "I will swear and forswear myself, rather than I will accuse myself to do me any harm".

[70][71] The other witness, Nicholas Skeres, had for many years acted as a confidence trickster, drawing young men into the clutches of people involved in the money-lending racket, including Marlowe's apparent killer, Ingram Frizer, with whom he was engaged in such a swindle.

Within weeks of his death, George Peele remembered him as "Marley, the Muses' darling"; Michael Drayton noted that he "Had in him those brave translunary things / That the first poets had" and Ben Jonson even wrote of "Marlowe's mighty line".

Believed by many scholars to be Marlowe's greatest success, Tamburlaine was the first English play written in blank verse and, with Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy, is generally considered the beginning of the mature phase of the Elizabethan theatre.

Late-twentieth-century scholarly consensus identifies 'A text' as more representative because it contains irregular character names and idiosyncratic spelling, which are believed to reflect the author's handwritten manuscript or "foul papers".

[108] Significance Considered by recent scholars as Marlowe's "most modern play" because of its probing treatment of the private life of a king and unflattering depiction of the power politics of the time.

[103] Significance The Massacre at Paris is considered Marlowe's most dangerous play, as agitators in London seized on its theme to advocate the murders of refugees from the low countries of the Spanish Netherlands, and it warns Elizabeth I of this possibility in its last scene.

[120] On 25 October 2011 a letter from Paul Edmondson and Stanley Wells was published by The Times newspaper, in which they called on the Dean and Chapter to remove the question mark on the grounds that it "flew in the face of a mass of unimpugnable evidence".