Guru

[2][5][6] By about mid 1st millennium CE, archaeological and epigraphical evidence suggest numerous larger institutions of gurus existed in India, some near Hindu temples, where guru-shishya tradition helped preserve, create and transmit various fields of knowledge.

[6] These gurus led broad ranges of studies including Hindu scriptures, Buddhist texts, grammar, philosophy, martial arts, music and painting.

A popular etymological theory considers the term "guru" to be based on the syllables gu (गु) and ru (रु), which it claims stands for darkness and "light that dispels it", respectively.

[2] Karen Pechilis states that, in the popular parlance, the "dispeller of darkness, one who points the way" definition for guru is common in the Indian tradition.

[32][33] In the Taittiriya Upanishad, the guru then urges a student to "struggle, discover and experience the Truth, which is the source, stay and end of the universe.

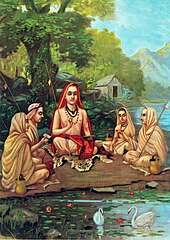

[41][42] The 8th century Hindu text Upadesasahasri of the Advaita Vedanta philosopher Adi Shankara discusses the role of the guru in assessing and guiding students.

The teacher possesses tranquility, self-control, compassion and a desire to help others, who is versed in the Śruti texts (Vedas, Upanishads), and unattached to pleasures here and hereafter, knows the subject and is established in that knowledge.

He is never a transgressor of the rules of conduct, devoid of weaknesses such as ostentation, pride, deceit, cunning, jugglery, jealousy, falsehood, egotism and attachment.

[35][53] At the Gurukul, the working student would study the basic traditional vedic sciences and various practical skills-oriented shastras[54] along with the religious texts contained within the Vedas and Upanishads.

[5][55][56] The education stage of a youth with a guru was referred to as Brahmacharya, and in some parts of India this followed the Upanayana or Vidyarambha rites of passage.

[7][60][61] Each ashram had a lineage of gurus, who would study and focus on certain schools of Hindu philosophy or trade,[54][55] also known as the guru-shishya parampara (teacher-student tradition).

[62][63] Inscriptions from 4th century CE suggest the existence of gurukuls around Hindu temples, called Ghatikas or Mathas, where the Vedas were studied.

[64] In south India, 9th century Vedic schools attached to Hindu temples were called Calai or Salai, and these provided free boarding and lodging to students and scholars.

[69] The Yajurveda and Atharvaveda texts state that knowledge is for everyone, and offer examples of women and people from all segments of society who are guru and participated in vedic studies.

[69][70][Note 6] Kramrisch, Scharfe, and Mookerji state that the guru tradition and availability of education extended to all segments of ancient and medieval society.

Swami Vivekananda said that there are many incompetent gurus, and that a true guru should understand the spirit of the scriptures, have a pure character and be free from sin, and should be selfless, without desire for money and fame.

"[82] A true guru guides and counsels a student's spiritual development because, states Yoga-Bija, endless logic and grammar leads to confusion, and not contentment.

[84] In modern neo-Hinduism, Kranenborg states guru may refer to entirely different concepts, such as a spiritual advisor, or someone who performs traditional rituals outside a temple, or an enlightened master in the field of tantra or yoga or eastern arts who derives his authority from his experience, or a reference by a group of devotees of a sect to someone considered a god-like Avatar by the sect.

[90] Initiations or ritual empowerments are necessary before the student is permitted to practice a particular tantra, in Vajrayana Buddhist sects found in Tibet and South Asia.

lama nampa shyi) in Tibetan Buddhism: In various Buddhist traditions, there are equivalent words for guru, which include Shastri (teacher), Kalyana Mitra (friendly guide, Pali: Kalyāṇa-mittatā), Acarya (master), and Vajra-Acarya (hierophant).

[93] The guru is literally understood as "weighty", states Alex Wayman, and it refers to the Buddhist tendency to increase the weight of canons and scriptures with their spiritual studies.

According to the American sociologist David G. Bromley this was partially due to the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1965 which permitted Asian gurus entrance to the US.

[105] In the Western world, the term is sometimes used in a derogatory way to refer to individuals who have allegedly exploited their followers' naiveté, particularly in certain cults or groups in the fields of hippie, new religious movements, self-help, and tantra.

[108] One example of such group was the Hare Krishna movement (ISKCON) founded by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada in 1966, many of whose followers voluntarily accepted the demanding lifestyle of bhakti yoga on a full-time basis, in stark contrast to much of the popular culture of the time.

[114] Dr. David C. Lane proposes a checklist consisting of seven points to assess gurus in his book, Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical.

For those wishing to devote their time and energy to the pursuit of conventional life, this kind of message is revolutionary, subversive, and profoundly disturbing".

Storr applies the term "guru" to figures as diverse as Jesus, Muhammad, Buddha, Gurdjieff, Rudolf Steiner, Carl Jung, Sigmund Freud, Jim Jones and David Koresh.

[117] Rob Preece, a psychotherapist and a practicing Buddhist, writes in The Noble Imperfection that while the teacher/disciple relationship can be an invaluable and fruitful experience, the process of relating to spiritual teachers also has its hazards.

[119][120] Jan van der Lans (1933–2002), a professor of the psychology of religion at the Catholic University of Nijmegen, wrote, in a book commissioned by the Netherlands-based Catholic Study Center for Mental Health, about followers of gurus and the potential dangers that exist when personal contact between the guru and the disciple is absent, such as an increased chance of idealization of the guru by the student (myth making and deification), and an increase of the chance of false mysticism.

[Note 8] In their 1993 book, The Guru Papers, authors Diana Alstad and Joel Kramer reject the guru-disciple tradition because of what they see as its structural defects.