Langerhans cell histiocytosis

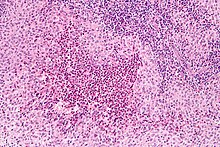

[1] LCH is part of a group of syndromes called histiocytoses, which are characterized by an abnormal proliferation of histiocytes (an archaic term for activated dendritic cells and macrophages).

[2] These diseases are related to other forms of abnormal proliferation of white blood cells, such as leukemias and lymphomas.

These cells in combination with lymphocytes, eosinophils, and normal histiocytes form typical LCH lesions that can be found in almost any organ.

When found in the lungs, it should be distinguished from Pulmonary Langerhans cell hystiocytosis—a special category of disease most commonly seen in adult smokers.

[9] This primary bone involvement helps to differentiate eosinophilic granuloma from other forms of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe or Hand-Schüller-Christian variant).

[10] Seen mostly in children, multifocal unisystem LCH is characterized by fever, bone lesions and diffuse eruptions, usually on the scalp and in the ear canals.

[12] Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH) is a unique form of LCH in that it occurs almost exclusively in cigarette smokers.

PLCH develops when an abundance of monoclonal CD1a-positive Langerhans (immature histiocytes) proliferate the bronchioles and alveolar interstitium, and this flood of histiocytes recruits granulocytes like eosinophils and neutrophils and agranulocytes like lymphocytes further destroying bronchioles and the interstitial alveolar space that can cause damage to the lungs.

[13] It is hypothesized that bronchiolar destruction in PLCH is first attributed to the special state of Langerhans cells that induce cytotoxic T-cell responses, and this is further supported by research that has shown an abundance of T-cells in early PLCH lesions that are CD4+ and present early activation markers.

[15] LCH provokes a non-specific inflammatory response, which includes fever, lethargy, and weight loss.

Arguments supporting the reactive nature of LCH include the occurrence of spontaneous remissions, the extensive secretion of multiple cytokines by dendritic cells and bystander-cells (a phenomenon known as cytokine storm) in the lesional tissue, favorable prognosis and relatively good survival rate in patients without organ dysfunction or risk organ involvement.

[24][25] On the other hand, the infiltration of organs by monoclonal population of pathologic cells, and the successful treatment of subset of disseminated disease using chemotherapeutic regimens are all consistent with a neoplastic process.

[35] Imaging may be evident in chest X-rays with micronodular and reticular changes of the lungs with cyst formation in advanced cases.

Endocrine deficiency often require lifelong supplement e.g. desmopressin for diabetes insipidus which can be applied as nasal drop.

[49] Although there is a general good prognosis for Langerhans cell histiocytosis, approximately 50% of patients with the disease are prone to various complications such as musculoskeletal disability, skin scarring and diabetes insipidus.