Languages of the Roman Empire

[7] Educated Romans, particularly those of the ruling elite, studied and often achieved a high degree of fluency in Greek, which was useful for diplomatic communications in the East even beyond the borders of the Empire.

Because communication in ancient society was predominantly oral, it can be difficult to determine the extent to which regional or local languages continued to be spoken or used for other purposes under Roman rule.

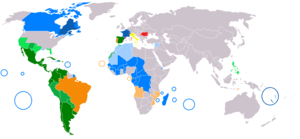

[14] After the decentralization of political power in late antiquity, Latin developed locally in the Western provinces into branches that became the Romance languages, including Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, Catalan, Occitan, Aromanian and Romanian.

[15] Latin itself remained an international medium of expression for diplomacy and for intellectual developments identified with Renaissance humanism up to the 17th century, and for law and the Roman Catholic Church to the present.

[27] Latin was not a requirement for Roman citizenship, and there was no state-supported schooling that privileged it as the medium for education: fluency was desirable for its "high cultural, political, legal, social and economic value".

The Imperial bureaucracy was so dependent on writing that the Babylonian Talmud (bT Shabbat 11a) declared "if all seas were ink, all reeds were pen, all skies parchment, and all men scribes, they would be unable to set down the full scope of the Roman government's concerns.

[36] An early form of story ballet (pantomimus) was brought to Rome by Greek performers and became popular throughout the multilingual empire in part because it relied on gesture rather than verbal expression.

[65] The satirist and rhetorician Lucian came from Samosata in the province of Syria; although he wrote in Greek, he calls himself a Syrian, and a reference to himself as a "barbarian" suggests that he spoke Syriac.

[69] At this time Coptic emerged as a fully literary language, including major translations of Greek scriptures, liturgical texts, and patristic works.

[85] The social custom of pledging mutual support among families or communities was compatible with hospitium in Roman culture, and the Celtiberians continued to produce the tokens, though switching to Latin, into the 2nd century of the Imperial era.

[92] The collection of pharmacological recipes by Marcellus of Bordeaux (late 4th or early 5th century) contains several Gaulish words, mainly plant names, and seems to indicate that the language remained in use for at least some purposes such as traditional medicine and magic.

[98] The officers and secretaries who kept the records preserved in the Vindolanda tablets were Batavian, but their Latin contains no hint; the common soldiers of their units, however, may have retained their Germanic speech.

[103] One striking example of multilingualism as well as multiculturalism in the Empire is a 2nd-century epitaph for a woman named Regina, discovered in 1878 near the Roman fort at South Shields, northeast England.

The inscription is written in Latin and Palmyrene Aramaic, the language of Regina's husband, Barates, who has been identified with a standardbearer (vexillarius) of that name from Palmyra, Syria.

[115] The importance of Latin in gaining access to the ruling power structure caused the rapid extinction of inscriptions in scripts that had been used to represent local languages on the Iberian peninsula (Hispania) and in Gaul.

[119] Their content indicates that Greek was used increasingly for specialized purposes: "education, medicine, acting, agonistic activities, art, magic, religion, including Christianity".

[123] The people of southwestern Gaul and northeastern Hispania (roughly present-day Aquitaine and Navarre) were regarded by Julius Caesar as ethnically distinct from the Celts, and the Aquitanian language they spoke was Vasconic like Basque, judging from place names.

[126] In the provinces of Africa westwards of Cyrenaica (a region colonized by Greeks since the 7th century BC), the people of Carthage and other Phoenician colonies spoke and wrote Punic, with Latin common in urban centers.

[116] Inscriptions might also be trilingual: one pertaining to Imperial cult presents "the official Latin, the local Punic, and the Greek of passing traders and an educated or cosmopolitan elite".

Although Libyan inscriptions are concentrated southeast of Hippo, near the present-day Algerian-Tunisia border, their distribution overall suggests that knowledge of the language was not confined to isolated communities.

Now-extinct languages in Anatolia included Galatian (the form of Celtic introduced by invading Gauls in the 3rd century BC), Phrygian, Pisidian, and Cappadocian, attested by Imperial-era inscriptions.

The ancient Macedonian language, perhaps a Greek dialect,[140] may have been spoken in some parts of what is now Macedonia and northern Greece; to the north of this area, Paeonian would have been used, and to the south Epirot, both scantily attested.

[8] Constantine, the first emperor to actively support Christianity, presumably knew some Greek, but Latin was spoken in his court, and he used an interpreter to address Greek-speaking bishops at the Council of Nicaea.

[172] Spells were not translated, because their efficacy was thought to reside in their precise wording;[173] a language such as Gaulish thus may have persisted for private ritual purposes when it no longer had everyday currency.

[182] While many voces magicae may be deliberate neologisms or obscurantism,[183] scholars have theorized that the more recognizable passages may be the products of garbled or misunderstood transmission, either in copying a source text or transcribing oral material.

[187] One of the oldest pieces of evidence of how Biblical quotations were used in magic designed to protect the dead is an inscription on a 3rd-century amulet capsule from around 260 AD found in archaeological excavations in the Praunheim district of Frankfurt am Main.

[189] Saint Jerome reports an odd story about a Frankish-Latin bilingual man of the Candidati Imperial bodyguard who, in a state of demonic possession, began speaking perfect Aramaic, a language he did not know.

Roman jurists show a concern for local languages such as Punic, Gaulish, and Aramaic in assuring the correct understanding and application of laws and oaths.

[196] The jurist Gaius distinguished between verbal contracts that derived their validity from formulaic utterance in Latin, and obligations expressing a mutual understanding of the ius gentium regardless of whether the parties were Roman or not.

[197] As an international language of learning and literature, Latin continued as an active medium of expression for diplomacy and for intellectual developments identified with Renaissance humanism up to the 17th century, and for law and the Roman Catholic Church to the present.

- "We're going to get naked" ([N]os nudi [f]iemus)

– "We came to drink" (Bibere venimus)

- "Now you're talking a lot" (Ia[m] multu[m] loquimini)

- "We may be called away" (Avocemur)

- "We're having three" [drinks] (Nos tres tenemus)

The scene may convey a proverbial expression equivalent to both " Let sleeping dogs lie " and "Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we may die." [ 1 ]