Lanthanum aluminate-strontium titanate interface

Individually, LaAlO3 and SrTiO3 are non-magnetic insulators, yet LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interfaces can exhibit electrical metallic conductivity,[1] superconductivity,[2] ferromagnetism,[3] large negative in-plane magnetoresistance,[4] and giant persistent photoconductivity.

[5] The study of how these properties emerge at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interface is a growing area of research in condensed matter physics.

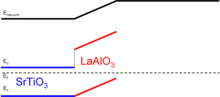

[1] It postulates that the LaAlO3, which is polar in the 001 direction (with alternating sheets of positive and negative charge), acts as an electrostatic gate on the semiconducting SrTiO3.

[1] When the LaAlO3 layer grows thicker than three unit cells, its valence band energy rises above the Fermi level, causing holes (or positively charged oxygen vacancies[9] ) to form on the outer surface of the LaAlO3.

The polar gating hypothesis also cannot explain why Ti3+ is detected when the LaAlO3 films are thinner than the critical thickness for conductivity.

An obvious difference between oxygen vacancies and polar gating in creating the interface conductivity is that the carriers from oxygen vacancies are thermally activated as the donor level of oxygen vacancies is usually separated from the SrTiO3 conduction band, consequently exhibiting the carrier freeze-out effect[22] at low temperatures; in contrast, the carriers originating from the polar gating are transferred into the SrTiO3 conduction band (Ti 3d orbitals) and are therefore degenerate.

[29] In 2011, researchers at Stanford University used a scanning SQUID to directly image the ferromagnetism, and found that it occurred in heterogeneous patches.

Magnetoresistance measurements are a major experimental tool used to understand the electronic properties of materials.

The magnetoresistance of LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interfaces has been used to reveal the 2D nature of conduction, carrier concentrations (through the hall effect), electron mobilities, and more.

[4] The large negative in-plane magnetoresistance has been ascribed to the interface's enhanced spin-orbit interaction.

A high-power laser ablates a LaAlO3 target, and the plume of ejected material is deposited onto a heated SrTiO3 substrate.

Typical conditions used are: Some LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interfaces have also been synthesized by molecular beam epitaxy, sputtering, and atomic layer deposition.

However, speculative applications have been suggested, including field-effect devices, sensors, photodetectors, and thermoelectrics;[53] related LaVO3/SrTiO3 is a functional solar cell[54] albeit hitherto with a low efficiency.