Scotland in the Late Middle Ages

However, the Auld Alliance with France led to the heavy defeat of a Scottish army at the Battle of Flodden in 1513 and the death of the king James IV, which would be followed by a long minority and a period of political instability.

[9] Despite the excommunication of Bruce and his followers by Pope Clement V, his support grew; and by 1314, with the help of leading nobles such as Sir James Douglas and the Earl of Moray, only the castles at Bothwell and Stirling remained under English control.

[16] Despite victories at Dupplin Moor (1332) and Halidon Hill (1333), in the face of tough Scottish resistance led by Sir Andrew Murray, the son of Wallace's comrade in arms, successive attempts to secure Balliol on the throne failed.

[24][25] In 1449 James II was declared to have reached his majority, but the Douglases consolidated their position and the king began a long struggle for power, leading to the murder of the 8th Earl of Douglas at Stirling Castle on 22 February 1452.

By this point, the alliance with England was failing and from 1480 there was intermittent war, followed by a full-scale invasion of Scotland two years later, led by the Duke of Gloucester, the future Richard III, and accompanied by Albany.

However, the king managed to alienate the barons, refusing to travel for the implementation of justice, preferring to be resident in Edinburgh, he debased the coinage, probably creating a financial crisis, he continued to pursue an English alliance and dismissed key supporters, including his Chancellor Colin Campbell, 1st Earl of Argyll, becoming estranged from his wife, Margaret of Denmark, and his son James.

He forced through the forfeiture of the lands of the last lord John MacDonald in 1493, backing Alexander Gordon, 3rd Earl of Huntly's power in the region and launching a series of naval campaigns and sieges that resulted in the capture or exile of his rivals by 1507.

However, he then established good diplomatic relations with England, and in 1502 signed the Treaty of Perpetual Peace, marrying Henry VII's daughter, Margaret Tudor, thus laying the foundation for the 17th century Union of the Crowns.

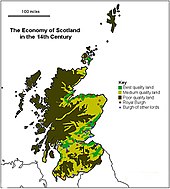

[37] The Central Lowland belt averages about 50 miles in width[38] and, because it contains most of the good quality agricultural land and has easier communications, could support most of the urbanisation and elements of conventional medieval government.

[48] The rural economy appears to have boomed in the 13th century and in the immediate aftermath of the Black Death was still buoyant, but by the 1360s there was a severe falling off of incomes, which can be seen in clerical benefices, of between a third and half compared with the beginning of the era.

As a result, the most important exports were unprocessed raw materials, including wool, hides, salt, fish, animals and coal, while Scotland remained frequently short of wood, iron and, in years of bad harvests, grain.

[31] Much more than the English monarchy, the Scottish court remained a largely itinerant institution, with the king moving between royal castles, particularly Perth and Stirling, but also holding judicial sessions throughout the kingdom, with Edinburgh only beginning to emerge as the capital in the reign of James III at the cost of considerable unpopularity.

[31] Like most Western European monarchies, the Scottish Crown in the 15th century adopted the example of the Burgundian court, through formality and elegance putting itself at the centre of culture and political life, defined with display, ritual and pageantry, reflected in elaborate new palaces and patronage of the arts.

By the end of the 15th century this group was being joined by increasing numbers of literate laymen, often secular lawyers, of which the most successful gained preferment in the judicial system and grants of lands and lordships.

[71][72] It acquired significant powers over particular issues, including consent for taxation, but it also had a strong influence over justice, foreign policy, war, and other legislation, whether political, ecclesiastical, social or economic.

[68] However, from about 1494, after his success against the Stewarts and Douglases and over rebels in 1482 and 1488, James IV managed to largely dispense with the institution and it might have declined, like many other systems of Estates in continental Europe, had it not been for his death in 1513 and another long minority.

Until the 15th century the ancient pattern of major lordships survived largely intact, with the addition of two new "scattered earldoms" of Douglas and Crawford, thanks to royal patronage after the Wars of Independence, mainly in the borders and south-west.

In the highlands James II created two new provincial earldoms for his favourites: Argyll for the Campbells and Huntly for the Gordons, which acted as a bulwark against the vast Lordship of the Isles built up by the Macdonalds.

They often formed the large close order defensive formations of shiltrons, able to counter mounted knights as they did at Bannockburn, but vulnerable to arrows (and later artillery fire) and relatively immobile, as they proved at Halidon Hill.

[82] James II had a royal gunner and received gifts of artillery from the continent, including two giant bombards made for Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, one of which, Mons Meg, still survives.

[92] Late medieval religion had its political aspects, with Robert I carrying the brecbennoch (or Monymusk reliquary), said to contain the remains of St. Columba, into battle at Bannockburn[93] and James IV using his pilgrimages to Tain and Whithorn to help bring Ross and Galloway under royal authority.

This led to the placement of clients and relatives of the king in key positions, including James IV's illegitimate son Alexander, who was nominated as Archbishop of St. Andrews at the age of 11, intensifying royal influence and also opening the Church to accusations of venality and nepotism.

[92] Traditional Protestant historiography tended to stress the corruption and unpopularity of the late medieval Scottish church, but more recent research has indicated how it met the spiritual needs of different social groups.

[94] Heresy, in the form of Lollardry, began to reach Scotland from England and Bohemia in the early 15th century, but despite evidence of a number of burnings of heretics and some apparent support for its anti-sacramental elements, it probably remained a relatively small movement.

In contrast to England, where the wealthy began to move towards more comfortable grand houses, these continued to be built into the modern period, developing into the style of Scottish Baronial architecture in the 19th century, popular amongst the minor aristocracy and merchant class.

[105] The grandest buildings of this type were the royal palaces in this style at Linlithgow, Holyrood, Falkland and the remodelled Stirling Castle,[106] all of which have elements of continental European architecture, particularly from France and the Low Countries, adapted to Scottish idioms and materials (particularly stone and harl).

[111] It was the dominant language of the lowlands and borders, brought there largely by Anglo-Saxon settlers from the 5th century, but began to be adopted by the ruling elite as they gradually abandoned French in the late medieval era.

The bardic tradition was not completely isolated from trends elsewhere, including love poetry influenced by continental developments and medical manuscripts from Padua, Salerno and Montpellier translated from Latin.

[111] The landmark work in the reign of James IV was Gavin Douglas's version of Virgil's Aeneid, the Eneados, which was the first complete translation of a major classical text in an Anglian language, finished in 1513, but overshadowed by the disaster at Flodden.

[122] The late Middle Ages has often been seen as the era in which Scottish national identity was initially forged, in opposition to English attempts to annexe the country and as a result of social and cultural changes.