Latin America during World War II

In order to better protect the Panama Canal, combat Axis influence, and optimize the production of goods for the war effort, the United States through Lend-Lease and similar programs greatly expanded its interests in Latin America, resulting in large-scale modernization and a major economic boost for the countries that participated.

[1][4][5] Brazil was the only country to send troops to the European Theater, was instrumental in providing air bases for the resupply of the combatants, and had an important part in the anti-submarine campaign of the Atlantic.

On the whole the Roosevelt policy was a political success, except in Argentina and Chile, which tolerated German influence, and refused to follow Washington's lead until the war was practically over.

[16] Following the December 7, 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, most of Latin America either severed relations with the Axis powers or declared war on them.

The demands of the American war industry and a scarcity of shipping caused many goods to be unavailable in Latin America, and so the prices for what was available increased.

In Peru, the government placed price controls on various products; hence, its foreign reserves did not increase as much as some of the other Latin American states and it lost badly-needed capital.

Mexican President Manuel Ávila Camacho capitalized on the situation to improve Mexico's bargaining position with the United States in general.

[1] Under Lend-Lease, Latin America received approximately $400 million in war materials in exchange for military bases and assisting in the defense of the Western Hemisphere.

[17] Out of all of the Latin American nations, Brazil benefited the most from Lend-Lease aid, mainly because of its geographical position at the northeastern corner of South America, which allowed for patrolling between South America and West Africa, as well as providing a ferry point for the transfer of American-made war materials to the Allies fighting in North Africa, but also because it was seen as a possible German invasion route that had to be defended.

Colombia and the Dominican Republic received Lend-Lease funds to modernize their militaries so they could assist in the defense of the Panama Canal and the Caribbean Sea lanes.

By 1943, the Pan-American Highway, built by the United States in part for defense purposes, ceased to be a priority, and so work on the road, as well as military aid, was halted.

Similar views were held by Jorge Ubico, Tiburcio Carias Andino, and Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, the dictators of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, respectively.

Chile and Argentina, on the other hand, allowed Axis agents to operate in their countries for most of the war, which was a source of considerable discord between the two nations and the United States.

Many of the Germans in Colombia were involved in the air transportation industry as employees of SCADTA, so the United States was concerned that they might be engaged in espionage or even plot to convert civilian aircraft into bombers for an attack against the Panama Canal.

Throughout much of the war, the Germans operated spy networks in all of the most prominent countries of the region, including Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Brazil, Cuba, Mexico, and others.

Operation Bolivar, as it was called, was centered on clandestine radio communications from their base in Argentina to Berlin in Germany, but it also utilized Spanish merchant vessels for the shipment of paper-form intelligence back to Europe.

Although Argentina and Chile eventually cracked down on the Axis agents operating in their countries in early 1944, some Bolivar activity continued up until the end of the European war in May 1945.

Prior to the beginning of the war in 1939, the propaganda focused on the superiority of German manufactured goods, and claimed that Germany was the center for scientific research, because it had the "world's most advanced educational system."

(Upon hearing of the final defeat of the German army, I, along with my country, remembered the admirable efforts of the heroic Soviet people during the years of struggle against fascist troops.

)[20] After World War I, in which Brazil was an ally of the United States, Great Britain, and France, the country realized it needed a more capable army but did not have the technology to create it.

Brazil remained neutral during the interwar but attended continental meetings in Buenos Aires, Argentina (1936); Lima, Peru (1938); and Havana, Cuba (1940) that obligated them to agree to defend any part of the Americas if attacked.

Initially, Brazil wanted to only provide resources and shelter for the war to have a chance of gaining a high postwar status but ended up sending 25,000 men to fight.

For example, USAID created family planning programs in Latin America combining the NGOs already in place, providing women in largely Catholic areas with access to contraception.

The Potrero del Llano, originally an Italian tanker, had been seized in port by the Mexican government in April 1941 and renamed for a region in Veracruz.

[26] A large part of Mexico's contribution to the war came through an agreement in January 1942 that allowed Mexican nationals living in the United States to join the U.S. armed forces.

[32] President Federico Laredo Brú led Cuba when war broke out in Europe, though real power belonged to Fulgencio Batista as the army's Chief of Staff.

The navy escorted hundreds of Allied ships through hostile waters, flew thousands of hours on convoy and patrol duty, and rescued over 200 victims of German U-boat attacks from the sea.

[36] Cuba received millions of dollars in American military aid through the Lend-Lease program, which included air bases, aircraft, weapons, and training.

[38] On May 3, 1942, German submarine U-125 sank the Dominican ship San Rafael with one torpedo and 32 rounds from the deck gun 50 miles west off Jamaica; one was killed, but 37 survived.

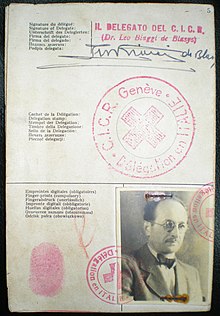

Gustav Wagner, an SS officer known as the “Beast,” died in Brazil in 1980 after the country’s supreme federal court refused to extradite him to Germany because of inaccuracies in the paperwork.