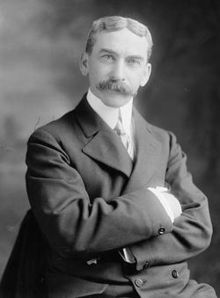

Francisco I. Madero

An advocate for social justice and democracy, his 1908 book The Presidential Succession in 1910 called Mexican voters to prevent the reelection of Porfirio Díaz, whose regime had become increasingly authoritarian.

After Díaz declared himself winner for an eighth term in a rigged election,[7] Madero escaped from jail, fled to the United States, and called for the overthrow of his regime in the Plan of San Luis Potosí, sparking the Mexican Revolution.

Madero was captured and assassinated along with vice president José María Pino Suárez in a series of events now called the Ten Tragic Days, where his brother Gustavo was tortured and killed.

In the north, Venustiano Carranza, then governor of Coahuila, led the nascent Constitutionalist Army; meanwhile, Zapata continued his rebellion against the federal government under the Plan of Ayala.

Once Huerta was ousted in July 1914, the revolutionary coalitions met in the Convention of Aguascalientes, where disagreements persisted, and Mexico entered a new stage of civil war.

Francisco Ignacio Madero González was born in 1873 into a large and extremely wealthy family in northeastern Mexico at the hacienda of El Rosario, in Parras de la Fuente, Coahuila.

During his time in Paris, Madero made a pilgrimage to the tomb of Allan Kardec, the founder of Spiritism, and became a passionate advocate of the belief, soon coming to believe he was a medium.

[28] On 2 April 1903, Bernardo Reyes, governor of Nuevo León, violently crushed a political demonstration, an example of the increasingly authoritarian policies of president Porfirio Díaz.

However, Madero argued that this was counterbalanced by the dramatic loss of freedom, including the brutal treatment of the Yaqui people, the repression of workers in Cananea, excessive concessions to the United States, and an unhealthy centralization of politics around the person of the president.

He founded the Anti-Re-election Center in Mexico City in May 1909, and soon thereafter lent his backing to the periodical El Antirreeleccionista, which was run by the young lawyer/philosopher José Vasconcelos and another intellectual, Luis Cabrera Lobato.

[34] In Puebla, Aquiles Serdán, from a politically engaged family, contacted Madero and as a result, formed an Anti-Re-electionist Club to organize for the 1910 elections, particularly among the working classes.

[36] At the meeting, Diaz told John Hays Hammond, "Since I am responsible for bringing several billion dollars in foreign investments into my country, I think I should continue in my position until a competent successor is found.

Moore, a Texas Ranger, discovered a man holding a concealed palm pistol along the procession route and they disarmed the assassin within only a few feet of Díaz and Taft.

Francisco Vázquez Gómez took over the nomination, but during Madero's time in jail, a fraudulent election was held on 21 June 1910 that gave Díaz an unbelievably large margin of victory.

At that point, Madero declared himself provisional President of Mexico, and called for a general refusal to acknowledge the central government, restitution of land to villages and Indian communities, and freedom for political prisoners.

[54] On 20 November 1910, Madero arrived at the border and planned to meet up with 400 men raised by his uncle Catarino Benavides Hernández to launch an attack on Ciudad Porfirio Díaz (modern-day Piedras Negras, Coahuila).

Two survivors of the Casas Grandes debacle were Giuseppe Garibaldi II, grandson of the famous Italian revolutionary, and General Benjamin Johannes Viljoen, an Afrikaner veteran of the Boer War.

In early May, Madero wanted to extend a ceasefire, but his fellow revolutionaries Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa disagreed and went ahead without orders on 8 May to attack Ciudad Juárez.

The Governor of Coahuila, Venustiano Carranza, and Luis Cabrera had strongly advised Madero not to sign the treaty, since it gave away the power the revolutionary forces had won.

The German ambassador to Mexico, Paul von Hintze, who associated with the Interim President, said of him that "De la Barra wants to accommodate himself with dignity to the inevitable advance of the ex-revolutionary influence, while accelerating the widespread collapse of the Madero party...."[58] Madero sought to be a moderate democrat and follow the course outlined in treaty bringing about exile of Díaz, but by calling for the disarming and demobilization of his revolutionary base, he undermined his support.

A curious fact is that almost immediately after taking office in November, Madero became the first head of state in the world to fly in an airplane, which the Mexican press was later to mock.

Emilio was the brother of Francisco Vázquez Gómez whom Madero replaced as the vice presidential candidate Pino Suárez when he successfully ran for president.

Unlike the two small, unsuccessful rebellions that attracted few followers, Orozco not only had an army to 8,000 men, he had backing from landowning interests, and a detailed battle plan to sweep through Chihuahua and capture Mexico City.

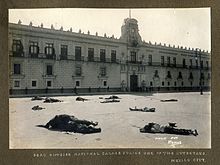

At 11:15 pm, reporters waiting outside the National Palace saw two cars containing Madero and Suárez emerge from the main gate under a heavy escort commanded by Major Francisco Cárdenas, an officer of the rurales.

A series of contemporary photographs taken by Manuel Ramos show Maderos's coffin being carried from the penitentiary and placed on a special funeral tram car for transportation to the cemetery.

Following Huerta's overthrow, Francisco Cárdenas fled to Guatemala where he committed suicide in 1920 after the new Mexican government had requested his extradition to stand trial for the murder of Madero.

[81][82] There was shock at Madero's murder, but there were many, including Mexican elites and foreign entrepreneurs and governments, who saw the coup and the emergence of General Huerta as the desired strongman to return order to Mexico.

In 1915, a Constitutionalist supporter created a chart outlining the political leaders of the time, calling Madero "The Great Democrat, elected president by the unanimous will of the people."

After three years as constitutional president, Carranza himself was ousted and killed in a 1920 coup by Sonoran revolutionary generals, Álvaro Obregón, Plutarco Elías Calles, and Adolfo de la Huerta.

His tomb had been an informal pilgrimage site on the anniversary of his murder (22 February) and the proclamation of his Plan of San Luis Potosí (20 November), which launched the Mexican Revolution.