Leaf

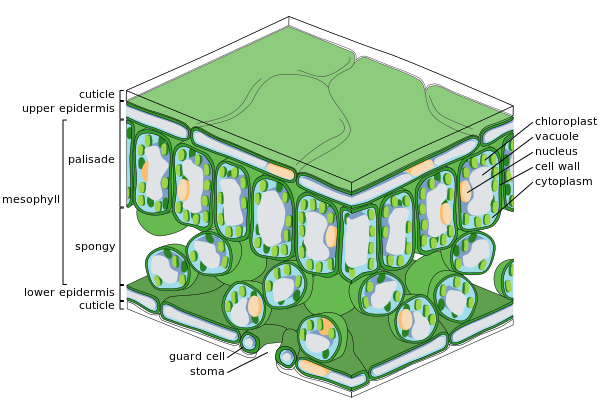

The leaf is an integral part of the stem system, and most leaves are flattened and have distinct upper (adaxial) and lower (abaxial) surfaces that differ in color, hairiness, the number of stomata (pores that intake and output gases), the amount and structure of epicuticular wax, and other features.

Leaves are mostly green in color due to the presence of a compound called chlorophyll which is essential for photosynthesis as it absorbs light energy from the Sun.

They capture the energy in sunlight and use it to make simple sugars, such as glucose and sucrose, from carbon dioxide (CO2) and water.

[6] Some leaf forms are adapted to modulate the amount of light they absorb to avoid or mitigate excessive heat, ultraviolet damage, or desiccation, or to sacrifice light-absorption efficiency in favor of protection from herbivory.

[6]: 445 The internal organization of most kinds of leaves has evolved to maximize exposure of the photosynthetic organelles (chloroplasts) to light and to increase the absorption of CO2 while at the same time controlling water loss.

In most plants, leaves also are the primary organs responsible for transpiration and guttation (beads of fluid forming at leaf margins).

The concentration of photosynthetic structures in leaves requires that they be richer in protein, minerals, and sugars than, say, woody stem tissues.

Correspondingly, leaves represent heavy investment on the part of the plants bearing them, and their retention or disposition are the subject of elaborate strategies for dealing with pest pressures, seasonal conditions, and protective measures such as the growth of thorns and the production of phytoliths, lignins, tannins and poisons.

The leaf-like organs of bryophytes (e.g., mosses and liverworts), known as phyllids, differ greatly morphologically from the leaves of vascular plants.

In most cases, they lack vascular tissue, are a single cell thick and have no cuticle, stomata, or internal system of intercellular spaces.

[13] Simple, vascularized leaves (microphylls), such as those of the early Devonian lycopsid Baragwanathia, first evolved as enations, extensions of the stem.

True leaves or euphylls of larger size and with more complex venation did not become widespread in other groups until the Devonian period, by which time the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere had dropped significantly.

This occurred independently in several separate lineages of vascular plants, in progymnosperms like Archaeopteris, in Sphenopsida, ferns and later in the gymnosperms and angiosperms.

[19] Dicot leaves have blades with pinnate venation (where major veins diverge from one large mid-vein and have smaller connecting networks between them).

[19] Monocot leaves in temperate climates usually have narrow blades and usually parallel venation converging at leaf tips or edges.

[20] A large variety of phyllotactic patterns occur in nature: In the simplest mathematical models of phyllotaxis, the apex of the stem is represented as a circle.

[24][25] Within the lamina of the leaf, while some vascular plants possess only a single vein, in most this vasculature generally divides (ramifies) according to a variety of patterns (venation) and form cylindrical bundles, usually lying in the median plane of the mesophyll, between the two layers of epidermis.

[29] In contrast, leaves with reticulate venation have a single (sometimes more) primary vein in the centre of the leaf, referred to as the midrib or costa, which is continuous with the vasculature of the petiole.

[29] Although it is the more complex pattern, branching veins appear to be plesiomorphic and in some form were present in ancient seed plants as long as 250 million years ago.

A pseudo-reticulate venation that is actually a highly modified penniparallel one is an autapomorphy of some Melanthiaceae, which are monocots; e.g., Paris quadrifolia (True-lover's Knot).

[36] The epidermis serves several functions: protection against water loss by way of transpiration, regulation of gas exchange and secretion of metabolic compounds.

[41][42] On the basis of molecular genetics, Eckardt and Baum (2010) concluded that "it is now generally accepted that compound leaves express both leaf and shoot properties.

However, horizontal alignment maximizes exposure to bending forces and failure from stresses such as wind, snow, hail, falling debris, animals, and abrasion from surrounding foliage and plant structures.

Thus, leaf design may involve compromise between carbon gain, thermoregulation and water loss on the one hand, and the cost of sustaining both static and dynamic loads.

In vascular plants, perpendicular forces are spread over a larger area and are relatively flexible in both bending and torsion, enabling elastic deforming without damage.

[47] Many leaves rely on hydrostatic support arranged around a skeleton of vascular tissue for their strength, which depends on maintaining leaf water status.

This shifts the balance from reliance on hydrostatic pressure to structural support, an obvious advantage where water is relatively scarce.

Red anthocyanin pigments are now thought to be produced in the leaf as it dies, possibly to mask the yellow hue left when the chlorophyll is lost—yellow leaves appear to attract herbivores such as aphids.

Further classification was then made on the basis of secondary veins, with 12 further types, such as; terms which had been used as subtypes in the original Hickey system.

[58] Further descriptions included the higher order, or minor veins and the patterns of areoles (see Leaf Architecture Working Group, Figures 28–29).

- Apex

- Midvein (Primary vein)

- Secondary vein.

- Lamina.

- Leaf margin

- Petiole

- Bud

- Stem

Bottom: skunk cabbage, Symplocarpus foetidus (simple leaf)

- Apex

- Primary vein

- Secondary vein

- Lamina

- Leaf margin

- Rachis