Golden Legend

[6] During the height of its popularity the book was so well known that the term "Golden Legend" was sometimes used generally to refer to any collection of stories about the saints.

Its repetitious nature is explained if Jacobus meant to write a compendium of saintly lore for sermons and preaching, not a work of popular entertainment.

The correct derivation is alluded to in the text, but set out in parallel to fanciful ones that lexicographers would consider quite wide of the mark.

Jacobus' etymologies have parallels in Isidore of Seville's Etymologiae, in which linguistically accurate derivations are set out beside allegorical and figurative explanations.

[12] The story then goes on to describe "Magumeth (Mahomet, Muhammad)" as "a false prophet and sorcerer", detailing his early life and travels as a merchant through his marriage to the widow Khadija, and goes on to suggest that his religious visions came as a result of epileptic seizures and the interventions of a renegade Nestorian monk named Sergius.

Such a tale is told of Saint Agatha; Jacobus da Varagine has pagans in Catania repairing to the relics of St. Agatha to supernaturally repel an eruption of Mount Etna: And for to prove that she had prayed for the salvation of the country, at the beginning of February, the year after her martyrdom, there arose a great fire, and came from the mountain toward the city of Catania and burnt the earth and stones, it was so fervent.

A typical example of the sort of story related, also involving St. Silvester, shows the saint receiving miraculous instruction from Saint Peter in a vision that enables him to exorcise a dragon: In this time it happed that there was at Rome a dragon in a pit, which every day slew with his breath more than three hundred men.

And when he came to the pit, he descended down one hundred and fifty steps, bearing with him two lanterns, and found the dragon, and said the words that S. Peter had said to him, and bound his mouth with the thread, and sealed it, and after returned, and as he came upward again he met with two enchanters which followed him for to see if he descended, which were almost dead of the stench of the dragon, whom he brought with him whole and sound, which anon were baptized, with a great multitude of people with them.

Thus was the city of Rome delivered from double death, that was from the culture and worshiping of false idols, and from the venom of the dragon.

[21]Jacobus describes the story of Saint Margaret of Antioch surviving being swallowed by a dragon as "apocryphal and not to be taken seriously" (trans.

The reason it stood out against competing saint collections probably is that it offered the average reader the perfect balance of information.

[25] It was also a major source for John Mirk's Festial, Osbern Bokenam's Legends of Hooly Wummen, and the Scottish Legendary.

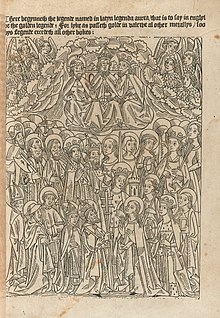

[28] In 1483, the work was re-translated and printed by William Caxton under the name The Golden Legende, and subsequently reprinted many times due to the demand.

[29] The adverse reaction to Legenda aurea under critical scrutiny in the 16th century was led by scholars who reexamined the criteria for judging hagiographic sources and found Legenda aurea wanting; prominent among the humanists were two disciples of Erasmus, Georg Witzel, in the preface to his Hagiologium, and Juan Luis Vives in De disciplinis.