Lesch–Nyhan syndrome

[3] The disorder was first recognized and clinically characterized by American medical student Michael Lesch and his mentor, pediatrician William Nyhan, at Johns Hopkins.

The combination of increased synthesis and decreased utilization of purines leads to high levels of uric acid production.

Beginning in the second year of life, a particularly striking feature of LNS is self-mutilating behaviors, characterized by lip and finger biting.

Neurological symptoms include facial grimacing, involuntary writhing, and repetitive movements of the arms and legs similar to those seen in Huntington's disease.

LNS is characterized by three major hallmarks: neurologic dysfunction, cognitive and behavioral disturbances including self-mutilation, and uric acid overproduction (hyperuricemia).

Damage to the basal ganglia causes affected individuals to adopt a characteristic fencing stance due to the nature of the lesion.

The most common presenting features are abnormally decreased muscle tone (hypotonia) and developmental delay, which are evident by three to six months of age.

Within the first few years of life, extrapyramidal involvement causes abnormal involuntary muscle contractions such as loss of motor control (dystonia), writhing motions (choreoathetosis), and arching of the spine (opisthotonus).

[15] The majority of individuals are cognitively impaired, which is sometimes difficult to distinguish from other symptoms because of the behavioral disturbances and motor deficits associated with the syndrome.

[18] LNS is due to mutations in the HPRT1 gene,[3][19] so named because it codes for the enzyme hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT or HGPRT, EC 2.4.2.8).

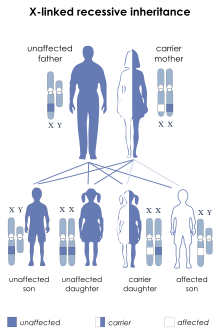

Female carriers have a second X chromosome, which contains a "normal" copy of HPRT, preventing the disease from developing, though they may have increased risk of hyperuricemia.

[citation needed] HGPRT is the "salvage enzyme" for the purines: it channels hypoxanthine and guanine back into DNA synthesis.

Failure of this enzyme has two results:[citation needed] It was previously unclear whether the neurological abnormalities in LNS were due to uric acid neurotoxicity or to a relative shortage in "new" purine nucleotides during essential synthesis steps.

Genetic mutations affecting the enzymes of the de novo synthesis pathway may possibly contribute to the disease, although these are rare or unknown.

[citation needed] Importantly, evidence suggests that one or more lesions in striatal dopaminergic pathways may be central to the neurological deficits, especially the choreoathetoid dyskinesia and self-mutilation.

This is based on the theory that uric acid is a powerful reducing agent and likely an important human antioxidant, in high concentration in blood.

Thus, it has been suggested that free radicals, oxidative stress, and reactive oxygen species may play some role in the neuropathology of LNS.

Likewise, 6-hydroxydopamine (the putative animal model for Lesch–Nyhan's neuropathy) apparently acts as a neurotoxin by generation of reactive oxygen species.

[citation needed] When an affected individual has fully developed the three clinical elements of uric acid overproduction, neurologic dysfunction, and cognitive and behavioral disturbances, diagnosis of LNS is easily made.

Signs of self-injurious behavior (SIB), results of pedigree analysis and novel molecular biology with genetic testing (called as Diagnostic triad for LNS), often confirms the diagnosis.

If only a suspected carrier female is available for mutation testing, it may be appropriate to grow her lymphocytes in 6-thioguanine (a purine analogue), which allows only HGPRT-deficient cells to survive.

[5] It is essential that the overproduction of uric acid be controlled in order to reduce the risk of nephropathy, nephrolithiasis, and gouty arthritis.

Even children treated from birth with allopurinol develop behavioral and neurologic problems, despite never having had high serum concentrations of uric acid.

Sixty percent of individuals have their teeth extracted[citation needed] in order to avoid self-injury, which families have found to be an effective management technique.

six Lesch–Nyhan syndrome patients, believed to be the largest concentration of LNS cases in one location, and is recognized as the leading source of information on care issues.

[citation needed] An article in the August 13, 2007 issue of The New Yorker magazine, written by Richard Preston, discusses "deep-brain stimulation" as a possible treatment.

The treatment involves invasive surgery to place wires that carry a continuous electric current into a specific region of the brain.

[30] An encouraging advance in the treatment of the neurobehavioural aspects of LNS was the publication in the October, 2006 issue of Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease of an experimental therapy giving oral S-adenosyl-methionine (SAMe).

The drug is available without prescription and has been widely used for depression, but its use for treating LNS should be undertaken only under strict medical supervision, as side effects are known.

[5] Michael Lesch was a medical student at Johns Hopkins and William Nyhan, a pediatrician and biochemical geneticist, was his mentor when the two identified LNS and its associated hyperuricemia in two affected brothers, ages 4 and 8.