Liberal feminism

As the oldest of the "Big Three" schools of feminist thought,[1] liberal feminism has its roots in 19th century first-wave feminism seeking recognition of women as equal citizens, focusing particularly on women's suffrage and access to education, the effort associated with 19th century liberalism and progressivism.

The sunflower and the color gold, taken to represent enlightenment, became widely used symbols of mainstream liberal feminism and women's suffrage from the 1860s, originally in the United States and later also in parts of Europe.

Early liberal feminists had to counter the assumption that only white men deserved to be full citizens.

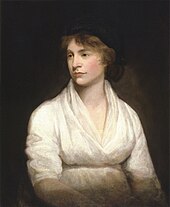

Pioneers such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Judith Sargent Murray, and Frances Wright advocated for women's full political inclusion.

Specific issues important to liberal feminists include but are not limited to reproductive rights and abortion access, sexual harassment, voting, education, fair compensation for work, affordable childcare, affordable health care, and bringing to light the frequency of sexual and domestic violence against women.

[23] A fair number of American liberal feminists believe that equality in pay, job opportunities, political structure, social security, and education for women especially needs to be guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution.

In February 1970, twenty NOW leaders disrupted the hearings of the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Amendments, demanding the ERA be heard by the full Congress.

In June, the ERA finally left the House Judiciary Committee due to a discharge petition filed by Representative Martha Griffiths.

Senator Sam Ervin and Representative Emanuel Celler succeeded in setting a time limit of seven years for ratification.

In 1978, Congress passed a disputed (less than supermajority) three-year extension on the original seven-year ratification limit, but the ERA could not gain approval by the needed number of states.

[25] According to Anthony Giddens, liberal feminist theory "believes gender inequality is produced by reduced access for women and girls to civil rights and allocation of social resources such as education and employment.

"[29] Political liberalism gave feminism a familiar platform for convincing others that their reforms "could and should be incorporated into existing law".

[30] Liberal feminists argued that women, like men, be regarded as autonomous individuals, and likewise be accorded the rights of such.

Liberal feminism emerged as a distinct political tradition during the Enlightenment (...) Liberal feminist theory emphasizes women's individual rights to autonomy and proposes remedies for gender inequities through, variously, removing legal and social constraints or advancing conditions that support women's equality.

"[33] Liberal feminist organizations are broadly inclusive and thus tend to support LGBT rights in the modern era.

The letter called upon the media and politicians "to no longer provide legitimate representation for those that share bigoted beliefs, that are aligned with far-right ideologies and seek nothing but harm and division" and stated that "these fringe internet accounts stand against affirmative medical care of transgender people, and they stand against the right to self-identification of transgender people in this country.

[67] The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy refers to Wendy McElroy, Joan Kennedy Taylor, Cathy Young, Rita Simon, Katie Roiphe, Diana Furchtgott-Roth, Christine Stolba, and Christina Hoff Sommers as equity feminists.

[67] Steven Pinker, an evolutionary psychologist, identifies himself as an equity feminist, which he defines as "a moral doctrine about equal treatment that makes no commitments regarding open empirical issues in psychology or biology".

Along with Judith Sargent Murray and Frances Wright, Wollstonecraft was one of the first major advocates for women's full inclusion in politics.

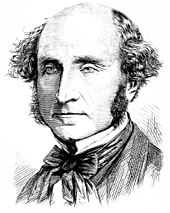

"[73] Mill frequently spoke of this imbalance and wondered if women were able to feel the same "genuine unselfishness" that men did in providing for their families.

Her book The Feminine Mystique, written in 1963, became a landmark bestseller and significantly influential by rebuking the fulfillment of middle-class women for domestic lives.

[80] Founders of NWPC include such prominent women as Gloria Steinem, author, lecturer and founding editor of Ms. Magazine; former Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm; former Congresswoman Bella Abzug; Dorothy Height, former president of the National Council of Negro Women; Jill Ruckelshaus, former U.S. Civil Rights Commissioner; Ann Lewis, former Political Director of the Democratic National Committee; Elly Peterson, former vice-chair of the Republican National Committee; LaDonna Harris, Indian rights leader; Liz Carpenter, author, lecturer and former press secretary to Lady Bird Johnson; and Eleanor Holmes Norton, Delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives and former chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

They believed legal, economic and social equity would come about only when women were equally represented among the nation's political decision-makers.

[82] The stated purposes of WEAL were: Norway has had a tradition of government-supported liberal feminism since 1884, when the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights (NKF) was founded with the support of the progressive establishment within the then-dominant governing Liberal Party (which received 63.4% of the votes in the election the following year).

Historians Cheris Kramarae and Paula A. Treichler noted that Colors were important in the iconography of the suffrage movement.

[88] Critics of liberal feminism argue that its individualist assumptions make it difficult to see the ways in which underlying social structures and values disadvantage women.

[89] According to Zhang and Rios, "liberal feminism tends to be adopted by 'mainstream' (i.e., middle-class) women who do not disagree with the current social structure."

[22] One of the leading scholars who have critiqued liberal feminism is radical feminist Catherine A. MacKinnon, an American lawyer, writer, and social activist.

[90] bell hooks' main criticism of the philosophies of liberal feminism is that they focus too much on an equality with men in their own class.

[91] She maintains that the "cultural basis of group oppression" is the biggest challenge, in that liberal feminists tend to ignore it.