Optical microscope

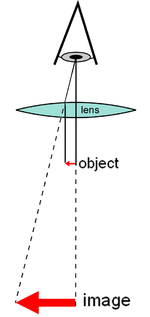

A compound microscope uses a system of lenses (one set enlarging the image produced by another) to achieve a much higher magnification of an object.

[1][2] The use of a single convex lens or groups of lenses are found in simple magnification devices such as the magnifying glass, loupes, and eyepieces for telescopes and microscopes.

Common compound microscopes often feature exchangeable objective lenses, allowing the user to quickly adjust the magnification.

Digital microscopy allows greater analysis of a microscope image, for example, measurements of distances and areas and quantitation of a fluorescent or histological stain.

It has been demonstrated that a light source providing pairs of entangled photons may minimize the risk of damage to the most light-sensitive samples.

[7] The earliest microscopes were single lens magnifying glasses with limited magnification, which date at least as far back as the widespread use of lenses in eyeglasses in the 13th century.

These include a claim 35[12] years after they appeared by Dutch spectacle-maker Johannes Zachariassen that his father, Zacharias Janssen, invented the compound microscope and/or the telescope as early as 1590.

[citation needed] Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1724) is credited with bringing the microscope to the attention of biologists, even though simple magnifying lenses were already being produced in the 16th century.

[23][24] While basic microscope technology and optics have been available for over 400 years it is much more recently that techniques in sample illumination were developed to generate the high quality images seen today.

[citation needed] The Nobel Prize in physics was awarded to Dutch physicist Frits Zernike in 1953 for his development of phase contrast illumination which allows imaging of transparent samples.

By using interference rather than absorption of light, extremely transparent samples, such as live mammalian cells, can be imaged without having to use staining techniques.

Just two years later, in 1955, Georges Nomarski published the theory for differential interference contrast microscopy, another interference-based imaging technique.

[citation needed] Modern biological microscopy depends heavily on the development of fluorescent probes for specific structures within a cell.

[citation needed] Since the mid-20th century chemical fluorescent stains, such as DAPI which binds to DNA, have been used to label specific structures within the cell.

[citation needed] At the lower end of a typical compound optical microscope, there are one or more objective lenses that collect light from the sample.

The stage usually has arms to hold slides (rectangular glass plates with typical dimensions of 25×75 mm, on which the specimen is mounted).

A mechanical stage, typical of medium and higher priced microscopes, allows tiny movements of the slide via control knobs that reposition the sample/slide as desired.

Most microscopes, however, have their own adjustable and controllable light source – often a halogen lamp, although illumination using LEDs and lasers are becoming a more common provision.

Modified environments such as the use of oil or ultraviolet light can increase the resolution and allow for resolved details at magnifications larger than 1,000x.

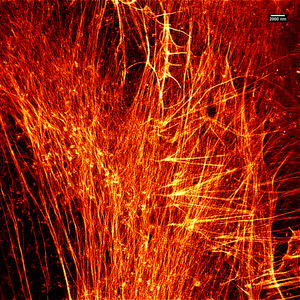

A recent technique (Sarfus) combines cross-polarized light and specific contrast-enhanced slides for the visualization of nanometric samples.

[citation needed] Modern microscopes allow more than just observation of transmitted light image of a sample; there are many techniques which can be used to extract other kinds of data.

[citation needed] Optical microscopy is used extensively in microelectronics, nanophysics, biotechnology, pharmaceutic research, mineralogy and microbiology.

Aside from applications needing true depth perception, the use of dual eyepieces reduces eye strain associated with long workdays at a microscopy station.

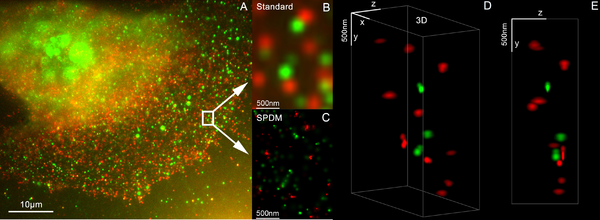

Examples include Vertico SMI, near field scanning optical microscopy which uses evanescent waves, and stimulated emission depletion.

[citation needed] On 8 October 2014, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Eric Betzig, William Moerner and Stefan Hell for the development of super-resolved fluorescence microscopy.

[38][39] SMI (spatially modulated illumination microscopy) is a light optical process of the so-called point spread function (PSF) engineering.

These are processes which modify the PSF of a microscope in a suitable manner to either increase the optical resolution, to maximize the precision of distance measurements of fluorescent objects that are small relative to the wavelength of the illuminating light, or to extract other structural parameters in the nanometer range.

Using this so-called SPDMphymod (physically modifiable fluorophores) technology a single laser wavelength of suitable intensity is sufficient for nanoimaging.

[citation needed] It is important to note that higher frequency waves have limited interaction with matter, for example soft tissues are relatively transparent to X-rays resulting in distinct sources of contrast and different target applications.

[citation needed] The use of electrons and X-rays in place of light allows much higher resolution – the wavelength of the radiation is shorter so the diffraction limit is lower.