Liverpool and Manchester Railway

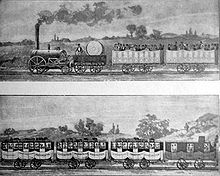

[4] It was also the first railway to rely exclusively on locomotives driven by steam power, with no horse-drawn traffic permitted at any time; the first to be entirely double track throughout its length; the first to have a true signalling system; the first to be fully timetabled; and the first to carry mail.

Cable haulage of freight trains was down the steeply-graded 1.26-mile (2.03 km) Wapping Tunnel to Liverpool Docks from Edge Hill junction.

The railway was primarily built to provide faster transport of raw materials, finished goods, and passengers between the Port of Liverpool and the cotton mills and factories of Manchester and surrounding towns.

Designed and built by George Stephenson, the line was financially successful, and influenced the development of railways across Britain in the 1830s.

[9][12] The proposed Liverpool and Manchester Railway was to be one of the earliest land-based public transport systems not using animal traction power.

[14] The original promoters are usually acknowledged to be Joseph Sandars, a rich Liverpool corn merchant, and John Kennedy, owner of the largest spinning mill in Manchester.

He advocated a national network of railways, based on what he had seen of the development of colliery lines and locomotive technology in the north of England.

Charles Lawrence was the Chairman, Lister Ellis, Robert Gladstone, John Moss and Joseph Sandars were the Deputy Chairmen.

The committee lost confidence in his ability to plan and build the line[23] and, in June 1824, George Stephenson was appointed principal engineer.

[24] As well as objections to the proposed route by Lords Sefton and Derby, Robert Haldane Bradshaw, a trustee of the Duke of Bridgewater's estate at Worsley, refused any access to land owned by the Bridgewater Trustees and Stephenson had difficulty producing a satisfactory survey of the proposed route and accepted James' original plans with spot checks.

Francis Giles suggested that putting the railway through Chat Moss was a serious error and the total cost of the line would be around £200,000 instead of the £40,000 quoted by Stephenson.

[27] Stephenson was cross examined by the opposing counsel led by Edward Hall Alderson and his lack of suitable figures and understanding of the work came to light.

[33] The railway route ran on a significantly different alignment, south of Stephenson's, avoiding properties owned by opponents of the previous bill.

In Liverpool, the route included a 1.25-mile (2.01 km) tunnel from Edge Hill to the docks, avoiding crossing any streets at ground level.

The Rennies insisted that the company should appoint a resident engineer, recommending either Josias Jessop or Thomas Telford, but would not consider George Stephenson except in an advisory capacity for locomotive design.

It was found impossible to drain the bog and so the engineers used a design from Robert Stannard, steward for William Roscoe, that used wrought iron rails supported by timber in a herring bone layout.

On 28 December, the Rocket travelled over the line carrying 40 passengers and crossed the Moss in 17 minutes, averaging 17 miles per hour (27 km/h).

[47] In April the following year, a test train carrying a 45-ton load crossed the moss at 15 miles per hour (24 km/h) without incident.

The L&MR had sought to de-emphasise the use of steam locomotives during the passage of the bill, the public were alarmed at the idea of monstrous machines which, if they did not explode, would fill the countryside with noxious fumes.

[54] To determine whether and which locomotives would be suitable, in October 1829 the directors organised a public competition, known as the Rainhill trials, which involved a run along a 1 mile (1.6 km) stretch of track.

The narrowness of the gap contributed to the first fatality, that of William Huskisson, and also made it dangerous to perform maintenance on one track while trains were operating on the other.

The somewhat subdued party proceeded to Manchester, where, the Duke being deeply unpopular with the weavers and mill workers, they were given a lively reception, and returned to Liverpool without alighting.

[67] Most stage coach companies operating between the two towns closed shortly after the railway opened as it was impossible to compete.

[76] Drivers could, and did, travel more quickly, but were reprimanded: it was found that excessive speeds forced apart the light rails, which were set onto individual stone blocks without cross-ties.

[84] Until 1844 handbells were used as emergency signals in foggy weather, though in that year small explosive boxes placed on the line began to be used instead.

have claimed the operation was the first Inter-city railway,[4] though that branding was not introduced until many years later and neither Manchester or Liverpool achieved city status until 1853 and 1880 respectively, nor would the distance between them qualify as long-haul.

This however has already started to change (from the May 2014 timetable) with new First TransPennine Express services between Newcastle/Manchester Victoria and Liverpool and between Manchester (Airport) and Scotland (via Chat Moss, Lowton and Wigan).

Northern also operates an hourly service calling at all stations from Liverpool Lime Street to Manchester Victoria.

[95] The historic passenger railway station of Manchester Liverpool Road is a Grade I Listed building, and was threatened by the Northern Hub plan.

The Science & Industry Museum, that is based at the former station premises, had initially objected to the scheme and an inquiry was set up in 2014 to investigate the potential damage to the historic structure.