Ordovician

[10] The Ordovician, named after the Welsh tribe of the Ordovices, was defined by Charles Lapworth in 1879 to resolve a dispute between followers of Adam Sedgwick and Roderick Murchison, who were placing the same rock beds in North Wales in the Cambrian and Silurian systems, respectively.

[14] Pre-existing Baltoscandic, British, Siberian, North American, Australian, Chinese, Mediterranean and North-Gondwanan regional stratigraphic schemes are also used locally.

[15] The Ordovician Period in Britain was traditionally broken into Early (Tremadocian and Arenig), Middle (Llanvirn (subdivided into Abereiddian and Llandeilian) and Llandeilo) and Late (Caradoc and Ashgill) epochs.

The corresponding rocks of the Ordovician System are referred to as coming from the Lower, Middle, or Upper part of the column.

Accretion of new crust was limited to the Iapetus margin of Laurentia; elsewhere, the pattern was of rifting in back-arc basins followed by remerger.

[29] There was vigorous tectonic activity along northwest margin of Gondwana during the Floian, 478 Ma, recorded in the Central Iberian Zone of Spain.

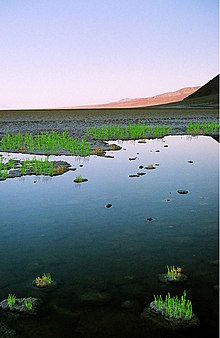

[18] Towards the end of the Ordovician, Gondwana began to drift across the South Pole; this contributed to the Hirnantian glaciation and the associated extinction event.

[45] The Dapingian and Sandbian saw major humidification events evidenced by trace metal concentrations in Baltoscandia from this time.

[50] Evidence suggests that global temperatures rose briefly in the early Katian (Boda Event), depositing bioherms and radiating fauna across Europe.

[52] The Ordovician saw the highest sea levels of the Paleozoic, and the low relief of the continents led to many shelf deposits being formed under hundreds of metres of water.

Sea levels fell steadily due to the cooling temperatures for about 3 million years leading up to the Hirnantian glaciation.

Shallow clear waters over continental shelves encouraged the growth of organisms that deposit calcium carbonates in their shells and hard parts.

For most of the Late Ordovician life continued to flourish, but at and near the end of the period there were mass-extinction events that seriously affected conodonts and planktonic forms like graptolites.

Brachiopods, bryozoans and echinoderms were also heavily affected, and the endocerid cephalopods died out completely, except for possible rare Silurian forms.

Their success epitomizes the greatly increased diversity of carbonate shell-secreting organisms in the Ordovician compared to the Cambrian.

[71] Molecular clock analyses suggest that early arachnids started living on land by the end of the Ordovician.

[82] This includes the distinctive Nemagraptus gracilis graptolite fauna, which was distributed widely during peak sea levels in the Sandbian.

It was long thought that the first true vertebrates (fish — Ostracoderms) appeared in the Ordovician, but recent discoveries in China reveal that they probably originated in the Early Cambrian.

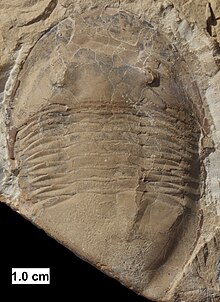

[88][89] In the Early Ordovician, trilobites were joined by many new types of organisms, including tabulate corals, strophomenid, rhynchonellid, and many new orthid brachiopods, bryozoans, planktonic graptolites and conodonts, and many types of molluscs and echinoderms, including the ophiuroids ("brittle stars") and the first sea stars.

[91] It is marked by a sudden abundance of hard substrate trace fossils such as Trypanites, Palaeosabella, Petroxestes and Osprioneides.

Bioerosion became an important process, particularly in the thick calcitic skeletons of corals, bryozoans and brachiopods, and on the extensive carbonate hardgrounds that appear in abundance at this time.

Terrestrial plants probably evolved from green algae, first appearing as tiny non-vascular forms resembling liverworts, in the middle to late Ordovician.

The extinctions occurred approximately 447–444 million years ago and mark the boundary between the Ordovician and the following Silurian Period.

At that time all complex multicellular organisms lived in the sea, and about 49% of genera of fauna disappeared forever; brachiopods and bryozoans were greatly reduced, along with many trilobite, conodont and graptolite families.

[99][100] The dip may have been caused by a burst of volcanic activity that deposited new silicate rocks, which draw CO2 out of the air as they erode.

[100] Another possibility is that bryophytes and lichens, which colonized land in the middle to late Ordovician, may have increased weathering enough to draw down CO2 levels.

For example, there is evidence the oceans became more deeply oxygenated during the glaciation, allowing unusual benthic organisms (Hirnantian fauna) to colonize the depths.

The rebound of life's diversity with the permanent re-flooding of continental shelves at the onset of the Silurian saw increased biodiversity within the surviving Orders.

[103] An alternate extinction hypothesis suggested that a ten-second gamma-ray burst could have destroyed the ozone layer and exposed terrestrial and marine surface-dwelling life to deadly ultraviolet radiation and initiated global cooling.

[104] Recent work considering the sequence stratigraphy of the Late Ordovician argues that the mass extinction was a single protracted episode lasting several hundred thousand years, with abrupt changes in water depth and sedimentation rate producing two pulses of last occurrences of species.