Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock

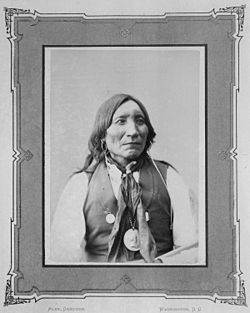

Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553 (1903), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case brought against the US government by the Kiowa chief Lone Wolf, who charged that Native American tribes under the Medicine Lodge Treaty had been defrauded of land by Congressional actions in violation of the treaty.

[5] The alliance made travel on the Santa Fe Trail hazardous, with attacks on wagon trains beginning in 1828 and continuing thereafter.

There was an attempt to place some of the tribes on a reservation on the Brazos River in Texas near Fort Belknap, under Indian Agent Robert S.

[fn 6] At the same time, Indian agents were trying to undermine tribal authority as the buffalo herds were being eliminated by white hunting.

[fn 9] During this same period, as the tribes had been unsuccessful at farming it, the KCA found a way to make the land pay by leasing it to cattlemen for grazing.

[28][29] Lone Wolf spoke out in opposition to the allotment, saying: Now we have several good schools on the reservation, and to them we intend to send our children, where they will be taught the arts of manual labor.

For that reason, because we are making such rapid progress, we ask the commission not to push us ahead too fast on the road we are to take.

[32] With the validity of the agreement in question, the tribes, joined by the Indian Rights Association (IRA) and local ranchers, lobbied against its ratification by Congress.

[fn 10][34] The IRA wrote letters to Senators, stating that the agreement was: "utterly destructive of that honor and good faith which should characterize our dealings with any people, and especially with one too weak to enforce their rights as against us by any other mean as than an appeal to our sense of justice.

[37] The agreement finally passed when the Rock Island Railroad agree to set aside an additional 480,000 acres of pastureland for the tribes to hold in common.

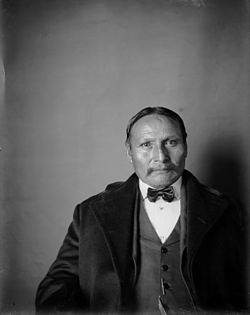

[38] At the ratification of the agreement, a delegation of tribal leaders[fn 12] traveled to Washington, D.C., and requested a meeting with President William McKinley.

[50] Judge A.C. Bradley ruled against Lone Wolf, holding that Congress had the authority to allot the land, citing United States v.

[53] The Court held that an act of Congress must prevail over any specific article in a treaty with an Indian tribe.

[58] Willis Van Devanter[fn 16] argued the case for the United States, taking the position that Congress had the power to abrogate the treaty at will.

The Court held that Congress had the authority to void treaty obligations with Native American tribes because it had an inherent plenary power,[61] noting: Authority over the tribal relations of the Indians has been exercised by Congress from the beginning, and the power has always been deemed a political one, not subject to be controlled by the judicial department of the government.

From their very weakness and helplessness, so largely due to the course of dealing of the Federal government with them and the treaties in which it has been promised, there arises the duty of protection, and with it the power.

[66] Until the Meriam Report was published, showing the destructive effects of the policy, the allotment process continued unchecked.

[68] Also, the Court's ruling meant that the only recourse left for Indian tribes to use to resolve land disputes was Congress.

Legally, scholars have compared Lone Wolf to the infamous Dred Scott case,[71][72][73] and universally condemned the decision.