Long-term potentiation

[5] Hebbian theory, introduced by Donald Hebb in 1949, echoed Ramón y Cajal's ideas, further proposing that cells may grow new connections or undergo metabolic and synaptic changes that enhance their ability to communicate and create a neural network of experiences:[6] Let us assume that the persistence or repetition of a reverberatory activity (or "trace") tends to induce lasting cellular changes that add to its stability....

Their results showed synaptic strength changes and researchers suggested that this may be due to a basic form of learning occurring within the slug.

[8][9] Though these theories of memory formation are now well established, they were farsighted for their time: late 19th and early 20th century neuroscientists and psychologists were not equipped with the neurophysiological techniques necessary for elucidating the biological underpinnings of learning in animals.

[10][11] There, Lømo conducted a series of neurophysiological experiments on anesthetized rabbits to explore the role of the hippocampus in short-term memory.

These experiments were carried out by stimulating presynaptic fibers of the perforant pathway and recording responses from a collection of postsynaptic cells of the dentate gyrus.

As expected, a single pulse of electrical stimulation to fibers of the perforant pathway caused excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) in cells of the dentate gyrus.

This phenomenon, whereby a high-frequency stimulus could produce a long-lived enhancement in the postsynaptic cells' response to subsequent single-pulse stimuli, was initially called "long-lasting potentiation".

[12][13] Timothy Bliss, who joined the Andersen laboratory in 1968,[10] collaborated with Lømo and in 1973 the two published the first characterization of long-lasting potentiation in the rabbit hippocampus.

[17] Since its original discovery in the rabbit hippocampus, LTP has been observed in a variety of other neural structures, including the cerebral cortex,[18] cerebellum,[19] amygdala,[20] and many others.

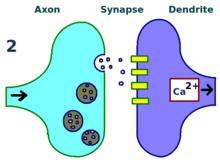

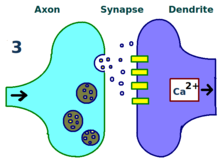

Borrowing its name from Hebb's postulate, summarized by the maxim that "cells that fire together wire together," Hebbian LTP requires simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic depolarization for its induction.

NMDA receptor-dependent LTP exhibits several properties, including input specificity, associativity, cooperativity, and persistence.

When the appropriate LTP-inducing stimulus arrives, nonsynaptic AMPA receptors are rapidly trafficked into the postsynaptic membrane under the influence of protein kinases.

By increasing the efficiency and number of AMPA receptors at the synapse, future excitatory stimuli generate larger postsynaptic responses.

[36] One hypothesis of this presynaptic facilitation is that persistent CaMKII activity in the postsynaptic cell during E-LTP may lead to the synthesis of a "retrograde messenger", discussed later.

[39] Recent research has shown that the induction of L-LTP can depend on coincident molecular events, namely PKA activation and calcium influx, that converge on CRTC1 (TORC1), a potent transcriptional coactivator for cAMP response element binding protein (CREB).

Upon activation, ERK may phosphorylate a number of cytoplasmic and nuclear molecules that ultimately result in the protein synthesis and morphological changes observed in L-LTP.

Regardless of their identities, it is thought that they contribute to the increase in dendritic spine number, surface area, and postsynaptic sensitivity to neurotransmitter associated with L-LTP expression.

[39] This reasoning was not seriously challenged until the 1980s, when investigators reported observing protein synthesis in dendrites whose connection to their cell body had been severed.

[39] Specifically, if indeed local protein synthesis underlies L-LTP, only dendritic spines receiving LTP-inducing stimuli will undergo LTP; the potentiation will not be propagated to adjacent synapses.

However, as discussed later, the synaptic tagging hypothesis successfully reconciles global protein synthesis, synapse specificity, and associativity.

Once there, the message presumably initiates a cascade of events that leads to a presynaptic component of expression, such as the increased probability of neurotransmitter vesicle release.

Rather, synaptic tagging explains the ability of weakly stimulated synapses, none of which are capable of independently generating LTP, to receive the products of protein synthesis initiated collectively.

For example, the steroid hormone estradiol may enhance LTP by driving CREB phosphorylation and subsequent dendritic spine growth.

During this exercise, normal rats are expected to associate the location of the hidden platform with salient cues placed at specific positions around the circumference of the maze.

Similarly, Susumu Tonegawa demonstrated in 1996 that the CA1 area of the hippocampus is crucial to the formation of spatial memories in living mice.

In 1999, Tang et al. produced a line of mice with enhanced NMDA receptor function by overexpressing the NR2B subunit in the hippocampus.

In a response to the article, Timothy Bliss and colleagues remarked that these and related experiments "substantially advance the case for LTP as a neural mechanism for memory.

Misprocessing of APP results in the accumulation of soluble Aβ that, according to Rowan's hypothesis, impairs hippocampal LTP and may lead to the cognitive decline seen early in AD.

turned its focus to LTP, owing to the hypothesis that drug addiction represents a powerful form of learning and memory.

[66] Addiction is a complex neurobehavioral phenomenon involving various parts of the brain, such as the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens (NAc).