Human cannibalism

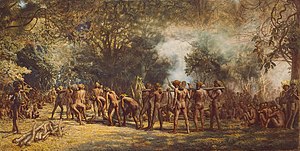

[6][7] The Island Caribs of the Lesser Antilles, whose name is the origin of the word cannibal, acquired a long-standing reputation as eaters of human flesh, reconfirmed when their legends were recorded in the 17th century.

[22][23] The word "cannibal" is derived from Spanish caníbal or caríbal, originally used as a name variant for the Kalinago (Island Caribs), a people from the West Indies said to have eaten human flesh.

[28] By contrast, survival cannibalism means "the consumption of others under conditions of starvation such as shipwreck, military siege, and famine, in which persons normally averse to the idea are driven [to it] by the will to live".

In parts of the Southern New Guinea lowland rain forests, hunting people "was an opportunistic extension of seasonal foraging or pillaging strategies", with human bodies just as welcome as those of animals as sources of protein, according to the anthropologist Bruce M. Knauft.

[64] While the term has been criticized as being too vague to clearly identify a specific type of cannibalism,[65] various records indicate that nutritional or culinary concerns could indeed play a role in such acts even outside of periods of starvation.

[98] On the other hand, the French philosopher Michel de Montaigne understood war cannibalism as a way of expressing vengeance and hatred towards one's enemies and celebrating one's victory over them, thus giving an interpretation that is close to modern explanations.

[103][104] As the daily energy need of an adult man is about 2,400 kilocalories, a dead male body could thus have fed a group of 25 men for a bit more than two days, provided they ate nothing but the human flesh alone – longer if it was part of a mixed diet.

[111] Emperor Wuzong of Tang supposedly ordered provincial officials to send him "the hearts and livers of fifteen-year-old boys and girls" when he had become seriously ill, hoping in vain that this folk "medicine" would cure him.

[121] During a massacre of the Madurese minority in the Indonesian part of Borneo in 1999, reporter Richard Lloyd Parry met a young cannibal who had just participated in a "human barbecue" and told him without hesitation: "It tastes just like chicken.

[125] After meeting a group of cannibals in West Africa in the 14th century, the Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta recorded that, according to their preferences, "the tastiest part of women's flesh is the palms and the breast.

"[126] Centuries later, the anthropologist Percy Amaury Talbot [fr] wrote that, in southern Nigeria, "the parts in greatest favour are the palms of the hands, the fingers and toes, and, of a woman, the breast.

"[127] Regarding the north of the country, his colleague Charles Kingsley Meek added: "Among all the cannibal tribes the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet were considered the tit-bits of the body.

"[128] Among the Apambia, a cannibalistic clan of the Azande people in Central Africa, palms and soles were considered the best parts of the human body, while their favourite dish was prepared with "fat from a woman's breast", according to the missionary and ethnographer F.

[131][130] When visiting the Solomon Islands in the 1980s, anthropologist Michael Krieger met a former cannibal who told him that women's breasts had been considered the best part of the human body because they were so fatty, with fat being a rare and sought delicacy.

[133][134] Based on theoretical considerations, the structuralist anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss suggested that human flesh was most typically boiled, with roasting also used to prepare the bodies of enemies and other outsiders in exocannibalism, but rarely in funerary endocannibalism (when eating deceased relatives).

[138] Human flesh was baked in steam on preheated rocks or in earth ovens (a technique widely used in the Pacific), smoked (which allowed to preserve it for later consumption), or eaten raw.

[143][144] In Cairo, Egypt, the Arab physician Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi repeatedly saw "little children, roasted or boiled", offered for sale in baskets on street corners during a heavy famine that started in 1200 CE.

[147] After the end of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), a Chinese writer criticized in his recollections of the period that some Mongol soldiers ate human flesh because of its taste rather than (as had also occurred in other times) merely in cases of necessity.

He added that they enjoyed torturing their victims (often children or women, whose flesh was preferred over that of men) by roasting them alive, in "large jars whose outside touched the fire [or] on an iron grate".

[125][150] Pedro de Margarit [es], who accompanied Christopher Columbus during his second voyage, afterwards stated "that he saw there with his own eyes several Indians skewered on spits being roasted over burning coals as a treat for the gluttonous.

Presently the mound swells and rises; little cracks appear, whence issue jets of steam diffusing a savoury odour; and in due time, of which the Fijians are excellent judges, the culinary process is complete.

The earth is then cautiously removed, the body lifted out, its wrappings taken off, its face painted, a wig or a turban placed upon its head, and there we have a "trussed frog" [as such steamed corpses were called] in all its unspeakable hideousness, staring at us with wide open, prominent, lack-lustre eyes.

[164] Similar customs had a long history: In Nuku Hiva, the largest of these islands, archaeologists found the partially consumed "remains of a young child" that had been roasted whole in an oven during the 14th century or earlier.

Homer's Odyssey, Beowulf, Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus, Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe, Herman Melville's Moby-Dick, and Gustave Flaubert's Salammbo are prominent examples.

Implicitly he assumes that everybody throughout human history must have shared the strong taboo placed by his own culture on cannibalism, but he never attempts to explain why this should be so, and "neither logic nor historical evidence justifies" this viewpoint, as Christian Siefkes commented.

Among the earliest reports of cannibalism in the Caribbean and the Americas, there are some (like those of Amerigo Vespucci) that seem to mostly consist of hearsay and "gross exaggerations", but others (by Chanca, Columbus himself, and other early travellers) show "genuine interest and respect for the natives" and include "numerous cases of sincere praise".

Condescending remarks can be found, but many Europeans who described cannibal customs in Central Africa wrote about those who practised them in quite positive terms, calling them "splendid" and "the finest people" and not rarely, like Chanca, actually considering them as "far in advance of" and "intellectually and morally superior" to the non-cannibals around them.

[191] This Horrid Practice: The Myth and Reality of Traditional Maori Cannibalism (2008) by New Zealand historian Paul Moon received a hostile reception by some Māori, who felt the book tarnished their whole people.

In the early modern and colonial era, shipwrecked sailors ate the bodies of the deceased or drew lots to decide who would have to die to provide food for the others – a widely accepted custom of the sea.

The Official Histories also document multiple instances of voluntary cannibalism, often involving young individuals offering some of their flesh to ill family members as a form of medical treatment.