Lute

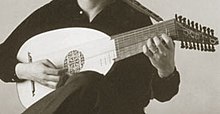

A lute (/ljuːt/[1] or /luːt/) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body.

He focuses on the longer lutes of Mesopotamia, various types of necked chordophones that developed throughout the ancient world: Indian (Gandhara and others), Greek, Egyptian (in the Middle Kingdom), Iranian (Elamite and others), Jewish/Israelite, Hittite, Roman, Bulgar, Turkic, Chinese, Armenian/Cilician cultures.

[17] He described the Gandhara lutes as having a "pear-shaped body tapering towards the short neck, a frontal stringholder, lateral pegs, and either four or five strings".

Under the Sasanians, a short almond-shaped lute from Bactria came to be called the barbat or barbud, which was developed into the later Islamic world's oud or ud.

[18] Among them was Abu l-Hasan 'Ali Ibn Nafi' (789–857),[19][20] a prominent musician, who had trained under Ishaq al-Mawsili (d. 850) in Baghdad and was exiled to Andalusia before 833.

These goods spread gradually to Provence, influencing French troubadours and trouvères and eventually reaching the rest of Europe.

[23] His Hohenstaufen grandson Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor (1194–1250) continued integrating Muslims into his court, including Moorish musicians.

Over the course of the Baroque era, the lute was increasingly relegated to the continuo accompaniment, and was eventually superseded in that role by keyboard instruments.

Music scholar Eckhard Neubauer suggested that oud may be an Arabic borrowing from the Persian word rōd or rūd, which meant string.

The sound hole is not open, but rather covered with a grille in the form of an intertwining vine or a decorative knot, carved directly out of the wood of the soundboard.

The lute belly is almost never finished, but in some cases the luthier may size the top with a very thin coat of shellac or glair to help keep it clean.

As the wood suffers dimensional changes through age and loss of humidity, it must retain a reasonably circular cross-section to function properly—as there are no gears or other mechanical aids for tuning the instrument.

Gut is more authentic for playing period pieces, though unfortunately it is also more susceptible to irregularity and pitch instability owing to changes in humidity.

Nylon offers greater tuning stability, but is seen as anachronistic by purists, as its timbre differs from the sound of earlier gut strings.

Important pioneers in lute revival were Julian Bream, Hans Neemann, Walter Gerwig, Suzanne Bloch and Diana Poulton.

Lute performances are now not uncommon; there are many professional lutenists, especially in Europe where the most employment is found, and new compositions for the instrument are being produced by composers.

Many are custom-built, but there is a growing number of luthiers who build lutes for general sale, and there is a fairly strong, if small, second-hand market.

Lutenistic practice has reached considerable heights in recent years, thanks to a growing number of world-class lutenists: Rolf Lislevand, Hopkinson Smith, Paul O'Dette, Christopher Wilke, Andreas Martin, Robert Barto, Eduardo Egüez, Edin Karamazov, Nigel North, Christopher Wilson, Luca Pianca, Yasunori Imamura, Anthony Bailes, Peter Croton, Xavier Diaz-Latorre, Evangelina Mascardi and Jakob Lindberg.

The improvisatory element, present to some degree in most lute pieces, is particularly evident in the early ricercares (not imitative as their later namesakes, but completely free), as well as in numerous preludial forms: preludes, tastar de corde ("testing the strings"), etc.

The leader of the next generation of Italian lutenists, Francesco Canova da Milano (1497–1543), is now acknowledged as one of the most famous lute composers in history.

The bigger part of his output consists of pieces called fantasias or ricercares, in which he makes extensive use of imitation and sequence, expanding the scope of lute polyphony.

French written lute music began, as far as we know, with Pierre Attaingnant's (c. 1494 – c. 1551) prints, which comprised preludes, dances and intabulations.

French lute music declined during the second part of the 16th century; however, various changes to the instrument (the increase of diapason strings, new tunings, etc.)

The last stage of French lute music is exemplified by Robert de Visée (c. 1655–1732/3), whose suites exploit the instrument's possibilities to the fullest.

Ottorino Respighi's famous orchestral suites called Ancient Airs and Dances are drawn from various books and articles on 16th- and 17th-century lute music transcribed by the musicologist Oscar Chilesotti, including eight pieces from a German manuscript Da un Codice Lauten-Buch, now in a private library in northern Italy.

The revival of lute-playing in the 20th century has its roots in the pioneering work of Arnold Dolmetsch (1858–1940); whose research into early music and instruments started the movement for authenticity.

At this time French lutenists began to explore the expressive capabilities of the lute through experimentation in tuning schemes on the instrument.

This development in tuning is credited to French lutenists of the early 17th century, who began increasing the number of major or minor thirds on the adjacent open strings of the 10-course lute.

Manuscript sources from the first half of the 17th century provide evidence that French transitional tunings gained popularity and were adopted across much of continental Europe.

Thus the 13-course lute played by composer Sylvius Leopold Weiss would have been tuned (A″A') (B″B') (C'C) (D'D) (E'E) (F'F) (G'G) (A'A') (DD) (FF) (AA) (d) (f), or with sharps or flats on the lower 7 courses appropriate to the key of the piece.