Lynching of Laura and L. D. Nelson

Her husband, Austin, pleaded guilty to larceny and was sent to the relative safety of the state prison in McAlester, while his wife and son were held in the county jail until their trial.

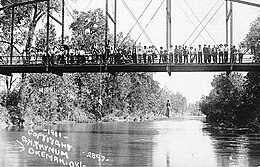

George Henry Farnum, the owner of Okemah's only photography studio, took photographs, which were distributed as postcards, a common practice at the time.

The political message—the promotion of white supremacy and black powerlessness—was an important element of the ritual, so that even the quieter lynchings might be photographed and the images published as postcards.

Described by the newspaper as a fearless man, he was known for having helped to stop the practice of bootlegging in Paden, on behalf of supporters of the local temperance movement.

[32][31] When the men entered the Nelsons' home, Loney asked Constable Martin to take the cap off a muzzle-loading shotgun that was hanging on the wall.

A bullet passed through Constable Martin's pant legs, grazing him in the thigh, then hit Loney in the hip and entered his abdomen.

[39][40] On May 10, before the same judge, Laura and L. D. (named by the Ledger as Mary and L. W. Nelson) were charged with murder and held without bail in the Okemah county jail.

[37] The Ledger reported on May 18, under the headline "Negro Female Prisoner Gets Unruly", that on May 13 Laura had been "bad" when the jailer, Lawrence Payne, brought her dinner.

The men went to the women's cells and removed Laura, described by the newspaper as "very small of stature, very black, about thirty-five years old, and vicious".

[39] According to a July 1911 report in The Crisis (the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), and a female witness who said she had seen the lynching or its aftermath, the men also took the baby.

[39] According to the Ledger, a fence post suspended on two chairs across a window was found in the jury room just after the lynching, near the cell where Laura had been held.

[7][42] The Ledger reported that the men gagged her and L. D. with tow sacks and, using rope made of half-inch hemp tied in a hangman's knot and hanged them from the bridge.

[1] The front page of The Okemah Ledger on May 25, 1911, said the lynching had been "executed with silent precision that makes it appear as a masterpiece of planning": The woman's arms were swinging by her side, untied, while about twenty feet away swung the boy with his clothes partly torn off and his hands tided with a saddle string.

Gently swaying in the wind, the ghastly spectacle was discovered this morning by a negro boy taking his cow to water.

"[d] The scene after the lynching was recorded in a series of photographs by George Henry Farnum, the owner of Okemah's only photography studio.

In May 1908, in an effort to stop the practice, the federal government amended the United States Postal Laws and Regulations to prevent "matter of a character tending to incite arson, murder or assassination" from being sent through the mail.

[e] James Allen bought the photo postcard of Laura Nelson, a 3 1/2 x 5 1/2 inch gelatin silver print, for $75 in a flea market.

Someone wrote on the back of one card, of the 1915 Will Stanley lynching in Temple, Texas: "This is the Barbecue we had last night My picture is to the left with a cross over it your son Joe.

"[52] The Independent wrote on May 25, 1911, that "[t]here is not a shadow of an excuse for the crime", and later called it a "terrible blot on Okfuskee County, a reproach that it will take years to remove".

Okemah's women and children were sent to spend the night in a nearby field, with the men standing guard on Main Street.

[54] Oswald Garrison Villard of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), wrote in protest to Lee Cruce, governor of Oklahoma.

"Hundreds of flea markets later," he wrote, "a trader pulled me aside and in conspiratorial tones offered to sell me a real photo postcard.

It was Laura Nelson hanging from a bridge, caught so pitiful and tattered and beyond retrieving—like a paper kite sagged on a utility wire.

They positioned and lit the corpses as if they were game birds, he wrote, and the postcards became an important part of the act, emphasizing its political nature.

Charley was an Okemah real-estate agent, district court clerk, Democratic politician, Freemason, and owner of the town's first automobile.

[63] There is no documentary evidence to support this;[64] the allegation stems from his younger brother, Claude, whom Klein interviewed on tape in 1977 for his book Woody Guthrie: A Life (1980).

[48][66] Seth Archer found the tape in 2005 in the Woody Guthrie Archives in New York, and reported Claude's statement in the Southwest Review in 2006.

[66]Woody Guthrie wrote two songs, unrecorded, about the Nelson's lynching, "Don't Kill My Baby and My Son"[67] and "High Balladree".

In one manuscript, he added at the end of the song: "Dedicated to the many negro mothers, fathers, and sons alike, that was lynched and hanged under the bridge of the Canadian River, seven miles south of Okemah, Okla., and to the day when such will be no more" (signed Woody G., February 29, 1940, New York).

"[8] Guthrie, "High Balladree": "A nickel postcard I buy off your rack / To show you what happens if / You're black and fight back / A lady and two boys hanging / down by their necks / From the rusty iron rigs / of my Canadian Bridge.