Magnetotactic bacteria

[1] Discovered in 1963 by Salvatore Bellini and rediscovered in 1975 by Richard Blakemore, this alignment is believed to aid these organisms in reaching regions of optimal oxygen concentration.

The publications were academic (peer-reviewed by the Istituto di Microbiologia's editorial committee under responsibility of the Institute's Director Prof. L. Bianchi, as usual in European universities at the time) and communicated in Italian with English, French and German short summaries in the official journal of a well-known institution, yet unexplainedly seem to have attracted little attention until they were brought to the attention of Richard Frankel in 2007.

It has been postulated that the evolutionary advantage of possessing a system of magnetosomes is linked to the ability to efficiently navigate within this zone of sharp chemical gradients by simplifying a potential three-dimensional search for more favorable conditions to a single dimension.

Some types of magnetotactic bacteria can produce magnetite even in anaerobic conditions, using nitric oxide, nitrate, or sulfate as a final acceptor for electrons.

[17] It has been suggested MTB evolved in the early Archean Eon, as the increase in atmospheric oxygen meant that there was an evolutionary advantage for organisms to have magnetic navigation.

There are 9 genes that are essential for the formation and function of modern magnetosomes: mamA, mamB, mamE, mamI, mamK, mamM, mamO, mamP, and mamQ.

Commonly observed morphotypes include spherical or ovoid cells (cocci), rod-shaped (bacilli), and spiral bacteria of various dimensions.

being Pseudomonadota, e.g. Magnetospirillum magneticum, an alphaproteobacterium, members of various phyla possess the magnetosome gene cluster, such as Candidatus Magnetobacterium bavaricum, a Nitrospira.

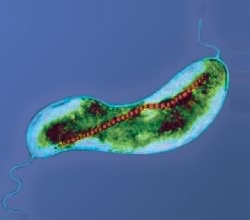

In the majority of MTB, the magnetosomes are aligned in chains of various lengths and numbers along the cell's long axis, which is magnetically the most efficient orientation.

However, dispersed aggregates or clusters of magnetosomes occur in some MTB, usually at one side of the cell, which often corresponds to the site of flagellar insertion.

The most abundant type of MTB occurring in environmental samples, especially sediments, are coccoid cells possessing two flagellar bundles on a somewhat flattened side.

In contrast, two of the morphologically more conspicuous MTB, regularly observed in natural samples, but never isolated in pure culture, are the MMP and a large rod containing copious amounts of hook-shaped magnetosomes (Magnetobacterium bavaricum).

[27] Some strains that swim persistently in one direction along the magnetic field (either north-seeking [NS] or south-seeking [SS])—mainly the magnetotactic cocci—are polar magneto-aerotactic.

In both cases, magnetotaxis increases the efficiency of aerotaxis in vertical concentration gradients by reducing a three-dimensional search to a single dimension.

One hint for the possible function of polar magnetotaxis could be that most of the representative microorganisms are characterised by possessing either large sulfur inclusions or magnetosomes consisting of iron-sulfides.

Microorganisms belonging to the genus Thioploca, for example, use nitrate, which is stored intracellularly, to oxidize sulfide, and have developed vertical sheaths in which bundles of motile filaments are located.

The biomineralisation of magnetite (Fe3O4) requires regulating mechanisms to control the concentration of iron, the crystal nucleation, the redox potential and the acidity (pH).

Sequence homology with proteins belonging to the ubiquitous cation diffusion facilitator (CDF) family and the "Htr-like" serine proteases has been found.

[16] The TPR domains are characterized by a folding consisting of two α-helices and include a highly conserved consensus sequence of 8 amino acids (of the 34 possible),[29] which is the most common in nature.

[30] The PDZ domains are structures that consist of 6 β-filaments and 2 α-helices that recognise the C-terminal amino acids of proteins in a sequence-specific manner.

The ferric ions must then be converted into the ferrous form (Fe2+), to be accumulated within the BMP; this is achieved by means of a transmembrane transporter, which exhibits sequence homology with a Na+/H+ antiporter.

One of these proteins, called Mms6, has also been employed for the artificial synthesis of magnetite, where its presence allows the production of crystals homogeneous in shape and size.

In cultures of Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum, iron can not be replaced with other transition metals (Ti, Cr, Co, Cu, Ni, Hg, Pb) commonly found in the soil.

[17] From a thermodynamic point of view, in the presence of a neutral pH and a low redox potential, the inorganic synthesis of magnetite is favoured when compared to those of other iron oxides.

These conclusions are also supported by the fact that MTB cultured in aerobic conditions (and thus nonmagnetic) contain amounts of iron comparable to any other species of bacteria.

However, the prerequisite for any large-scale commercial application is mass cultivation of magnetotactic bacteria or the introduction and expression of the genes responsible for magnetosome synthesis into a bacterium, e.g., E. coli, that can be grown relatively cheaply to extremely large yields.