Magnet

The word magnet was adopted in Middle English from Latin magnetum "lodestone", ultimately from Greek μαγνῆτις [λίθος] (magnētis [lithos])[1] meaning "[stone] from Magnesia",[2] a place in Anatolia where lodestones were found (today Manisa in modern-day Turkey).

The earliest known surviving descriptions of magnets and their properties are from Anatolia, India, and China around 2,500 years ago.

[3][4][5] The properties of lodestones and their affinity for iron were written of by Pliny the Elder in his encyclopedia Naturalis Historia in the 1st century AD.

[11] In 1820, Hans Christian Ørsted discovered that a compass needle is deflected by a nearby electric current.

In the same year André-Marie Ampère showed that iron can be magnetized by inserting it in an electrically fed solenoid.

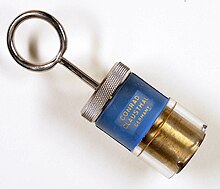

[7] Joseph Henry further developed the electromagnet into a commercial product in 1830–1831, giving people access to strong magnetic fields for the first time.

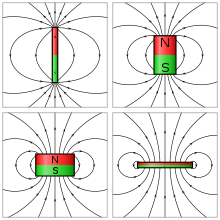

[17] A wire in the shape of a circle with area A and carrying current I has a magnetic moment of magnitude equal to IA.

If a ferromagnetic foreign body is present in human tissue, an external magnetic field interacting with it can pose a serious safety risk.

If a pacemaker has been embedded in a patient's chest (usually for the purpose of monitoring and regulating the heart for steady electrically induced beats), care should be taken to keep it away from magnetic fields.

Because of the way their regular crystalline atomic structure causes their spins to interact, some metals are ferromagnetic when found in their natural states, as ores.

These include iron ore (magnetite or lodestone), cobalt and nickel, as well as the rare earth metals gadolinium and dysprosium (when at a very low temperature).

Given the low cost of the materials and manufacturing methods, inexpensive magnets (or non-magnetized ferromagnetic cores, for use in electronic components such as portable AM radio antennas) of various shapes can be easily mass-produced.

Sintering offers superior mechanical characteristics, whereas casting delivers higher magnetic fields and allows for the design of intricate shapes.

Alnico magnets resist corrosion and have physical properties more forgiving than ferrite, but not quite as desirable as a metal.

Trade names for alloys in this family include: Alni, Alcomax, Hycomax, Columax, and Ticonal.

Flexible magnets are composed of a high-coercivity ferromagnetic compound (usually ferric oxide) mixed with a resinous polymer binder.

[39] For magnetic compounds (e.g. Nd2Fe14B) that are vulnerable to a grain boundary corrosion problem it gives additional protection.

In the 1990s, it was discovered that certain molecules containing paramagnetic metal ions are capable of storing a magnetic moment at very low temperatures.

Very briefly, the two main attributes of an SMM are: Most SMMs contain manganese but can also be found with vanadium, iron, nickel and cobalt clusters.

More recently, it has been found that some chain systems can also display a magnetization that persists for long times at higher temperatures.

Some nano-structured materials exhibit energy waves, called magnons, that coalesce into a common ground state in the manner of a Bose–Einstein condensate.

[40][41] The United States Department of Energy has identified a need to find substitutes for rare-earth metals in permanent-magnet technology, and has begun funding such research.

These cost more per kilogram than most other magnetic materials but, owing to their intense field, are smaller and cheaper in many applications.

The maximum usable temperature is highest for alnico magnets at over 540 °C (1,000 °F), around 300 °C (570 °F) for ferrite and SmCo, about 140 °C (280 °F) for NIB and lower for flexible ceramics, but the exact numbers depend on the grade of material.

[47] If the coil of wire is wrapped around a material with no special magnetic properties (e.g., cardboard), it will tend to generate a very weak field.

Uses for electromagnets include particle accelerators, electric motors, junkyard cranes, and magnetic resonance imaging machines.

Both hard and soft magnets have a more complex, history-dependent, behavior described by what are called hysteresis loops, which give either B vs. H or M vs. H. In CGS, M = χH, but χSI = 4πχCGS, and μ = μr.

If a magnet is acting vertically, it can lift a mass m in kilograms given by the simple equation: where g is the gravitational acceleration.

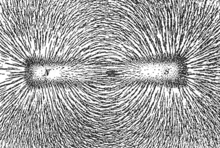

The equation is valid only for cases in which the effect of fringing is negligible and the volume of the air gap is much smaller than that of the magnetized material:[52][53] where: The force between two identical cylindrical bar magnets placed end to end at large distance

is approximately:[dubious – discuss],[52] where: Note that all these formulations are based on Gilbert's model, which is usable in relatively great distances.