Main Customs Office (Munich)

[1] It is renowned as an exemplary representation of the "monumental architecture of the Prince Regent period" showcasing the grandeur and independence of the Bavarian kingdom.

Since 1807, Bavaria had a well-organized financial administration that included a General-Zoll- und Maut-Direktion (General Customs and Toll Directorate).

[7] An expansion on the existing site was not feasible, prompting the government to commission a new building for the Munich I Main Customs Office in 1908.

Rank and Heilmann & Littmann were responsible for the execution of the reinforced concrete structures, while the wrought iron work was carried out by F. F. Kustermann.

[14] During the early years of the Main Customs Office, the storage space was not fully utilized, resulting in parts of the building being rented out to local companies in Munich.

The building suffered partial damage from demolition bombs during air raids and was also looted by the Munich population the night before the U.S. Army arrived.

[17] After the war, the Americans used approximately two-thirds of the warehouse as a PX depot, making alterations that resulted in the loss of many artistic and structural details.

In 1999, Christian Dior presented its fall/winter collection in the counter hall, and the auditing room was transformed into a dance studio for the ZDF Christmas series Anna.

[22] The Technical Examination and Training Institute underwent extensive renovation from 2011 to 2014 after its laboratories were relocated to a new building near Munich Airport.

[25] To this day, these structures continue to shape the city's landscape, reflecting a commitment to exceptional quality and making Munich not only a cultural hub renowned for its art, music, theater, literature, and science but also reached the "peak of Munich's national and European importance" in architecture at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century.

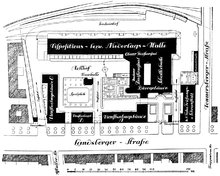

The layout is designed as a multi-wing complex, featuring buildings of varying heights arranged in a stepped manner, along with several courtyards and green spaces.

The street-facing facade is defined by archways and walls, giving the complex a distinct character akin to a self-contained fortress for work and living purposes.

"The administrative building, serving as the actual Customs Office, is oriented in a north-south direction, featuring a prominent façade with a convex gable and clock tower.

Set back from Landsberger Straße, its entrance area is accessed through a courtyard of honor, framed by the testing facility to the east and the side wing of one of the residential buildings.

[31] Notable features include a barrel vault with robust reinforced concrete frame trusses and ceiling surfaces adorned with coffered stucco.

Adjacent to the counter hall is the lower auditing room, with an atrium between them extending to the basement, providing vehicle access to the cellars via a ramp.

The light well, originally open to the storage areas, was mostly closed off after the renovations, as the warehouse floors were converted into office spaces.

Situated to the east of the Ehrenhof, the Technical Examination and Training Institute of the Customs Administration comprised office and business rooms, several laboratories, and a central lecture hall equipped with modern slide projectors and an extensive collection of sample goods.

All apartments were equipped with gas stoves and central heating, ensuring a high standard of living for ordinary employees.

[21] The complex's architectural appeal is further enhanced by the varying building heights and the diverse roofscape, featuring dormers and dwarf houses.

[10] To prevent dust, the exhaust air from the examination rooms underwent filtration, and the adjoining offices were maintained under slight positive pressure.

The customs office had its own transformer to convert electricity from the main station's power plant to the required voltage levels.

Notably, the director's office retains its original wood paneling and furnishings, providing a glimpse into the historical atmosphere of the period.

[8] During the restoration between 1977 and 1987, the counter hall required professional repairs to fix ceiling cracks caused by war damage.

Under layers of plaster, the original front wall made of shell limestone slabs and columns was uncovered and exposed.

After consultation with the State Office for the Preservation of Historical Monuments, the impression of the glazing of the light well, which had been closed in the meantime, was suggested by painted-on glass blocks.

During the renovation, a coating similar to lime slabs was used as a replacement, allowing visitors to still experience the grandeur of this historic space while preserving its cultural significance.