Manchester computers

[2] As the world's first stored-program computer, the Baby, and the Manchester Mark 1 developed from it, quickly attracted the attention of the United Kingdom government, who contracted the electrical engineering firm of Ferranti to produce a commercial version.

Work on the machine began in 1947, and on 21 June 1948 the computer successfully ran its first program, consisting of 17 instructions written to find the highest proper factor of 218 (262,144) by trying every integer from 218 − 1 downwards.

[12] Its successful operation was reported in a letter to the journal Nature published in September 1948,[13] establishing it as the world's first stored-program computer.

Development of the Manchester Mark 1 began in August 1948, with the initial aim of providing the university with a more realistic computing facility.

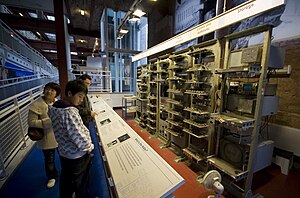

[15] The Final Specification machine, which was fully working by October 1949,[16] contained 4,050 valves and had a power consumption of 25 kilowatts.

[17] Perhaps the Manchester Mark 1's most significant innovation was its incorporation of index registers, commonplace on modern computers.

[19] As a result of experience gained from the Mark 1, the developers concluded that computers would be used more in scientific roles than pure maths.

Two of Kilburn's team, Richard Grimsdale and D. C. Webb, were assigned to the task of designing and building a machine using the newly developed transistors instead of valves, which became known as the Manchester TC.

The machine[clarification needed] did however make use of valves to generate its 125 kHz clock waveforms and in the circuitry to read and write on its magnetic drum memory, so it was not the first completely transistorised computer, a distinction that went to the Harwell CADET of 1955.

At the end of 1958 Ferranti agreed to collaborate with Manchester University on the project, and the computer was shortly afterwards renamed Atlas, with the joint venture under the control of Tom Kilburn.

The first Atlas was officially commissioned on 7 December 1962, and was considered at that time to be the most powerful computer in the world, equivalent to four IBM 7094s.

[31] Two other machines were built: one for a joint British Petroleum/University of London consortium, and the other for the Atlas Computer Laboratory at Chilton near Oxford.

An outline proposal for a successor to Atlas was presented at the 1968 IFIP Conference in Edinburgh,[35] although work on the project and talks with ICT (of which Ferranti had become part) aimed at obtaining their assistance and support had begun in 1966.

MU5 was fully operational by October 1974, coinciding with ICL's announcement that it was working on the development of a new range of computers, the 2900 series.

A prototype model of MU6V, based on 68000 microprocessors with vector orders emulated as "extracodes" was constructed and tested but not further developed beyond this.

MU6-G was built with a grant from SRC and successfully ran as a service machine in the Department between 1982 and 1987,[4] using the MUSS operating system developed as part of the MU5 project.