Mangrove

[1][2] Mangrove plant families first appeared during the Late Cretaceous to Paleocene epochs and became widely distributed in part due to the movement of tectonic plates.

Mangrove forests serve as vital habitats for a diverse array of aquatic species, offering a unique ecosystem that supports the intricate interplay of marine life and terrestrial vegetation.

[2][9][10] The success of mangrove restoration may depend heavily on engagement with local stakeholders, and on careful assessment to ensure that growing conditions will be suitable for the species chosen.

[15] Other possibilities include the Malay language manggi-manggi[13][12] The English usage may reflect a corruption via folk etymology of the words mangrow and grove.

[17] Demonstrating convergent evolution, many of these species found similar solutions to the tropical conditions of variable salinity, tidal range (inundation), anaerobic soils, and intense sunlight.

[21] The black mangrove (Avicennia germinans) lives on higher ground and develops many specialized root-like structures called pneumatophores, which stick up out of the soil like straws for breathing.

Anaerobic bacteria liberate nitrogen gas, soluble ferrum (iron), inorganic phosphates, sulfides, and methane, which make the soil much less nutritious.

[citation needed] Pneumatophores (aerial roots) allow mangroves to absorb gases directly from the atmosphere, and other nutrients such as iron, from the inhospitable soil.

A captive red mangrove grows only if its leaves are misted with fresh water several times a week, simulating frequent tropical rainstorms.

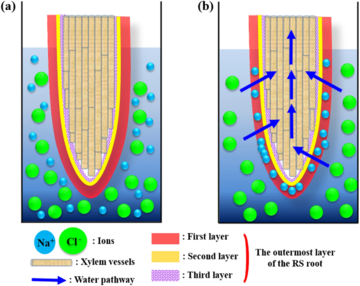

[27] A 2016 study by Kim et al. investigated the biophysical characteristics of sea water filtration in the roots of the mangrove Rhizophora stylosa from a plant hydrodynamic point of view.

The study provides insights into the mechanism underlying water filtration through halophyte roots and could serve as a basis for the development of a bio-inspired method of desalination.

These outliers result either from unbroken coastlines and island chains or from reliable supplies of propagules floating on warm ocean currents from rich mangrove regions.

[38]: 57 "At the limits of distribution, the formation is represented by scrubby, usually monotypic Avicennia-dominated vegetation, as at Westonport Bay and Corner Inlet, Victoria, Australia.

In the northern hemisphere, scrubby Avicennia gerrninans in Florida occurs as far north as St. Augustine on the east coast and Cedar Point on the west.

Thus, for a plant to survive in this environment, it must tolerate broad ranges of salinity, temperature, and moisture, as well as several other key environmental factors—thus only a select few species make up the mangrove tree community.

[42] Mangrove plants require a number of physiological adaptations to overcome the problems of low environmental oxygen levels, high salinity, and frequent tidal flooding.

[43] Once established, mangrove roots provide an oyster habitat and slow water flow, thereby enhancing sediment deposition in areas where it is already occurring.

Mangrove removal disturbs these underlying sediments, often creating problems of trace metal contamination of seawater and organisms of the area.

[45] Because of the uniqueness of mangrove ecosystems and the protection against erosion they provide, they are often the object of conservation programs,[4] including national biodiversity action plans.

[51] In areas where roots are permanently submerged, the organisms they host include algae, barnacles, oysters, sponges, and bryozoans, which all require a hard surface for anchoring while they filter-feed.

The intricate root systems of mangroves create a habitat conducive to the proliferation of microorganisms, crustaceans, and small fish, forming the foundational tiers of the food chain.

Additionally, mangrove forests function as essential nurseries for many commercially important fish species, providing a sheltered environment rich in nutrients during their early life stages.

In summary, mangrove forests play a crucial and unbiased role in sustaining biodiversity and ecological balance within coastal food webs.

The ecosystem provides little competition and minimizes threats of predation to juvenile lemon sharks as they use the cover of mangroves to practice hunting before entering the food web of the ocean.

[60] However, an additional complication is the imported marine organic matter that also gets deposited in the sediment due to the tidal flushing of mangrove forests.

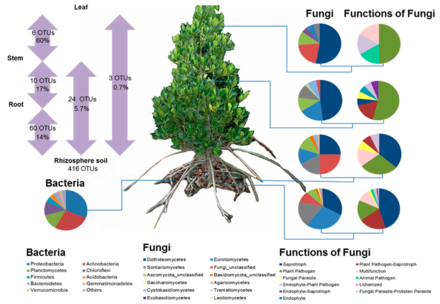

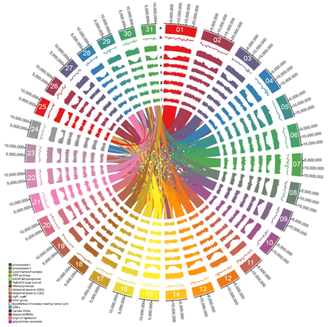

[72][73][78] Recent studies have investigated the detailed structure of root-associated microbial communities at a continuous fine-scale in other plants,[85] where a microhabitat was divided into four root compartments: endosphere,[75][86][87] episphere,[75] rhizosphere,[86][88] and nonrhizosphere or bulk soil.

Thus, based on studies by Lai et al.'s systematic review, here they suggest sampling improvements and a fundamental environmental index for future reference.

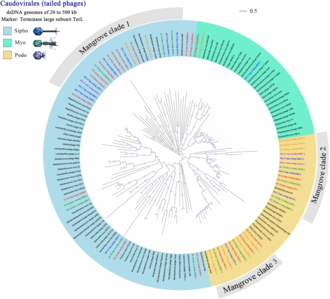

[99][105] AMGs have been extensively explored in marine cyanophages and include genes involved in photosynthesis, carbon turnover, phosphate uptake and stress response.

[103][110][111][112] Interestingly, a recent analysis of Pacific Ocean Virome data identified niche-specialised AMGs that contribute to depth-stratified host adaptations.

[115][116] Most mangrove carbon is stored in soil and sizable belowground pools of dead roots, aiding in the conservation and recycling of nutrients beneath forests.

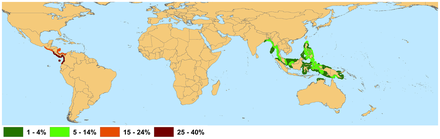

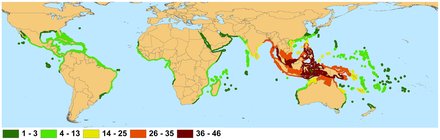

Colour-coded number ranges indicate number of species.

Not shown are introduced ranges: Rhizophora stylosa in French Polynesia, Bruguiera sexangula , Conocarpus erectus , and Rhizophora mangle in Hawaii, Sonneratia apelata in China, and Nypa fruticans in Cameroon and Nigeria.