Manifesto of Futurism

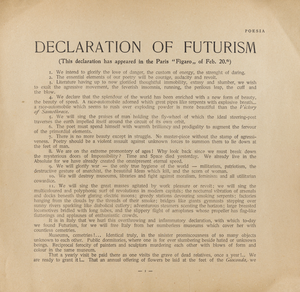

[1] In it, Marinetti expresses an artistic philosophy called Futurism, which rejected the past and celebrated speed, machinery, violence, youth, and industry.

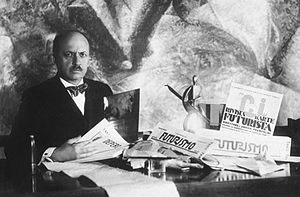

Marinetti wrote the manifesto in the autumn of 1908, and it first appeared as a preface to a volume of his poems, published in Milan in January 1909.

Their response included the use of deliberate excesses to demonstrate the existence of a dynamic, surviving Italian intellectual class.

Poetry would help man embrace the idea that his soul is part of this transformation (see articles 6 and 7), introducing a new concept of beauty rooted in the human instinct for aggression.

However, Futurism scholar Günter Berghaus argues that Marinetti's stance against "feminism" in Article 10 is unclear, especially when contrasted with his publication of works by women Futurists in the literary journal Poesia.

However, the political movements underlying these events were already well-established and undoubtedly informed Marinetti's thinking, while his publication subsequently influenced them.

[12] At the time of its publication, the manifesto was frequently cited as an "imagining of the future" for some of these political movements, glorifying violence and conflict, and calling for the destruction of cultural institutions like museums and libraries.

In reality, objects are not separate from one another or their surroundings: "The sixteen people around you in a rolling motor bus are in turn and at the same time one, ten four three; they are motionless and they change places.