Manned Orbiting Laboratory

A single uncrewed test flight of the Gemini B spacecraft was conducted on 3 November 1966, but the MOL was canceled in June 1969 without any crewed missions being flown.

At the height of the Cold War in the mid-1950s, the United States Air Force (USAF) was particularly interested in the Soviet Union's military and industrial capabilities.

Twenty-four U-2 missions produced images of about 15 percent of the country with a maximum resolution of 0.61 meters (2 ft) before the downing of a U-2 in 1960 abruptly ended the program.

[7] In February 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered the USAF to proceed as quickly as possible with Corona as a joint interim project with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

[14] On 25 August 1962, Zuckert informed General Bernard Adolph Schriever, the commander of the AFSC, that he was to proceed with studies of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) as the director of the program.

[35] Although reconnaissance was its main purpose, "manned orbiting laboratory" was still an accurate description; the program hoped to prove that astronauts could perform militarily useful tasks in a shirt-sleeve environment in space for up to thirty days.

He also noted that while countries had not objected to satellites passing overhead, a crewed space station might be a different matter,[38] but the Secretary of State, Dean Rusk, thought that this could be managed.

[45] Schriever retired from the Air Force in August 1966, and was succeeded as head of the AFSC and MOL Program Director by Major General James Ferguson.

The program did not accept applications; 15 candidates were selected and sent to Brooks Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas, for a week of medical evaluation in October 1964.

[62] They only knew of the cover story that the program would be a space laboratory for military experiments, and did not learn of the reconnaissance role until after selection; they were advised to resign if they disliked the classified aspect.

By avoiding cloudy areas and identifying more interesting subjects (an open missile silo instead of a closed one, for example), they would save film,[68] the major limitation, since it had to be returned in the small Gemini B spacecraft.

As a result of the Apollo 1 fire in January 1967, in which three NASA astronauts were killed in a ground test of their spacecraft, the MOL was switched to use a helium-oxygen atmosphere instead of a pure oxygen one.

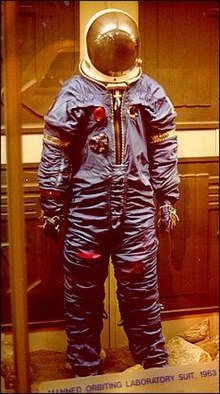

The NASA astronauts had custom-made sets of flight, training and backup suits, but for the MOL the intention was that spacesuits would be provided in standard sizes with adjustable elements.

MOL needed to be flown in a polar orbit, but a launch due south from Cape Kennedy would overfly southern Florida, which raised safety concerns.

The Chairman of the House Committee on Science and Astronautics, Congressman George P. Miller from California, convened a special hearing on the MOL program on 7 February 1966.

[92] The USAF attempted to purchase the land to the south of Vandenberg Air Force Base for the new space launch complex from the owners, but negotiations failed to reach agreement on a suitable price.

To prepare for this contingency, an agreement was reached with Chile on 26 July 1968 for the use of Easter Island as a staging area for search and rescue aircraft and helicopters.

[80] Works included resurfacing the 2,000-meter (6,600 ft) runway, taxiways and parking areas with asphalt, and establishing communications, aircraft maintenance and storage facilities, and accommodation for 100 personnel.

[112] In August 1965, the first uncrewed qualification flight had been expected to take place in late 1968, with the first crewed mission in early 1970,[113][114] on the assumption that engineering development would commence in January 1966.

[112] When the MOL engineering development phase commenced in September 1966, it became clear that the USAF estimates of project costs and those of the major contractors were a long way apart.

On 15 July 1968, the MOL SPO convened a conference with major contractors in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, and it was agreed to defer the first crewed mission from August to December 1971.

[119] Human reconnaissance from space was tested on Gemini 5 in 1965, which conducted 17 USAF military experiments, including photographing missile launches from Vandenberg Air Force Base, and observations of the White Sands Proving Ground.

The report, which was submitted on 25 May 1966, concluded that they would be useful in several ways, but implied that the program would always need to justify the cost and difficulty of the MOL versus a robotic version.

It concluded that it would help identify smaller items and features, and increase the understanding of Soviet procedures and processes, and the capacities of some of its industrial facilities, it would not alter estimates of technical capabilities, or assessments of the size and deployment of forces.

Whether the benefit justified the cost was unclear,[120] but by 1968 USAF decided that the automated system's longer development time and less certain capability meant that the first MOL missions required astronauts.

In a last ditch attempt to save MOL, Laird, Seamans, and Stewart met with Nixon at the White House on 17 May, and briefed him on the history of the program.

[70] Lew Allen, who worked in NRO and became a USAF general in the 1970s, thought that deciding to build an unmanned MOL resulted in design changes that caused the program's cancellation.

[137] Although describing his training as a payload specialist for STS-62-A as "the most exciting time of my life", Edward C. Aldridge, Jr.—NRO head during the mid-1980s—said in 2009 that MOL was canceled: ... because we couldn't find where having men in that satellite was beneficial.

The Director of Space Systems, Brigadier General Allen, became the point of contact for contracts that were terminated, but those with Aerojet, McDonnell Douglas, and the United Technologies Corporation (UTC) were still open in June 1973.

Homer about the MOL program, Spies in Space (2019), was based on documents released by the NRO and interviews she conducted with Abrahamson, Bobko, Crippen, Crews, Macleay, and Truly.